Zirconium is a versatile transition metal whose properties and compounds have shaped technologies from ancient jewelry to modern nuclear reactors. This article explores where it is found, how it is processed, and the many applications that depend on its unique combination of strength, corrosion resistance and chemical behavior. You will also find interesting tangents about gemstones, high-performance ceramics and the challenges of separating zirconium from its close chemical cousin, hafnium.

Occurrence and mineralogy

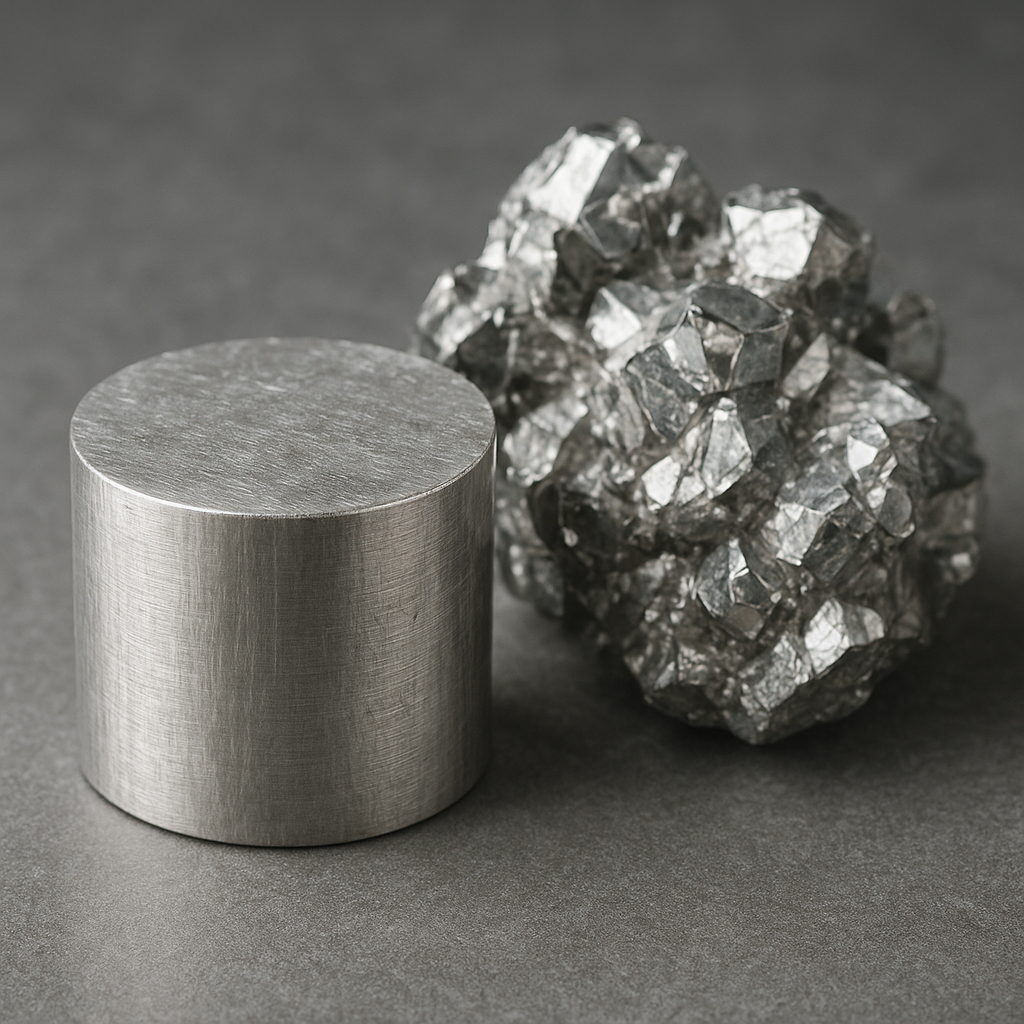

Zirconium seldom appears in nature as the free metal; instead it is bound in minerals. The most common mineral source is zircon (ZrSiO4), a resilient silicate that forms in igneous and metamorphic rocks and accumulates in heavy-mineral sands through erosional processes. Other ores include baddeleyite (ZrO2) and complex zirconium-bearing accessory minerals. Mining typically targets beach and dune deposits where dense minerals concentrate, as well as hard-rock sources.

The global distribution of zirconium-bearing minerals mirrors the geology of continental crust. Major producers of zircon sands include Australia, South Africa, India and Brazil. Mining and processing of these deposits yield concentrates that are the feedstock for both zirconium metal production and zircon-based ceramics and refractories.

- Zircon is prized not only as an ore but also as a gemstone; natural zircons show a wide range of colors and can be exceptionally brilliant.

- Baddeleyite serves as a direct oxide source; it is less common but valuable when present in igneous rocks such as anorthosite.

- Accessory minerals in heavy-mineral sands include rutile and ilmenite; mineral separation uses gravity, magnetic and electrostatic methods.

Extraction and refining processes

Converting mineral concentrates into metallic zirconium involves several steps. For ceramic and refractory uses, zircon is processed to produce zirconia (ZrO2) or used directly as ground mineral. For metallic zirconium, an intermediate compound—zirconium tetrachloride (ZrCl4)—is typically prepared, purified and then reduced.

The most common industrial route to metal is the so-called Kroll process. In this multi-step method, purified ZrCl4 is reduced with molten magnesium or sodium to yield sponge zirconium, which must be further purified and often melted multiple times to remove impurities such as oxygen, nitrogen and residual halides.

A persistent metallurgical challenge is separation of hafnium, which is chemically similar and co-occurs with zirconium in minerals. Hafnium has a very high neutron absorption cross-section, so for nuclear applications zirconium must be virtually free of hafnium. Separation methods include solvent extraction, fractional distillation of volatile halides and ion-exchange techniques.

Physical and chemical properties

Zirconium (atomic number 40) sits in group 4 of the periodic table, alongside titanium and hafnium. Its metal is strong, ductile and has a high melting point. A key feature is the rapid formation of a thin, protective oxide layer that provides excellent corrosion resistance in many environments, including seawater and many acids. This passive film, primarily zirconium dioxide, is the reason zirconium and its alloys are used where long-term chemical stability is required.

Chemically, zirconium forms stable compounds with oxygen, nitrogen and carbon, and reacts vigorously with nonmetals at high temperature. Zirconium dioxide has several crystalline forms—monoclinic, tetragonal and cubic—each with different mechanical and thermal behavior. Stabilizing additives such as yttria create yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ), a material with exceptional thermal and ionic properties.

Major industrial applications

Zirconium’s combination of properties supports a wide range of industries. Below are the principal application areas and why zirconium is chosen.

Nuclear industry

The nuclear power sector is perhaps the most prominent high-profile user of zirconium. Zirconium alloys, commonly known as Zircaloys, serve as fuel-cladding materials in light-water reactors because of their low neutron absorption cross-section and strong corrosion resistance at high temperatures. These alloys must have extremely low hafnium content, adding complexity and cost to production. Advanced reactor designs and accident-tolerant fuel concepts continue to drive research into improved zirconium alloys and coatings.

Ceramics and refractories

Zirconia ceramics are prized for hardness, wear resistance and high-temperature stability. Applications include grinding media, thermal barrier coatings, crucibles and foundry molds where dimensional stability and resistance to molten metals are critical. Zircon-based refractories are used in steelmaking, furnace linings and investment casting processes. The tetragonal and cubic phases of zirconia, especially when stabilized, offer toughness and fracture resistance that enable structural ceramic parts.

Jewelry and gem trade

Natural zircon gemstones have been valued for centuries. Their brilliance and range of colors—yellow, red, blue and colorless—made them popular long before the advent of synthetic diamond simulants. In contrast, cubic zirconia (CZ) is a synthesized form of stabilized zirconia commonly used as an affordable diamond substitute in jewelry. The distinction between natural zircon and synthetic cubic zirconia is important for gemologists and consumers.

Medical and dental uses

Zirconia ceramics are now commonplace in dentistry. Yttria-stabilized zirconia provides high strength, good fracture toughness and excellent aesthetics for crowns and bridges. Its biocompatibility and resistance to wear make it attractive for implants and abutments where metal allergies are a concern. Metallic zirconium and its alloys have also been explored for biomedical implants, but zirconia ceramics dominate due to favorable surface properties and low ion release.

Electrochemical and energy devices

YSZ is a high-temperature oxygen ion conductor and is central to solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) and oxygen sensors (lambda sensors in automotive exhaust systems). At elevated temperatures, oxygen ions migrate through the stabilized zirconia lattice, allowing it to function as a solid electrolyte. Its thermal stability and ionic conductivity make zirconia a core component of high-efficiency energy conversion devices.

Advanced and emerging technologies

Recent research expands zirconium’s role into new frontiers. Examples include:

- Nanostructured zirconia for catalyst supports and high-surface-area ceramics capable of withstanding corrosive environments.

- Zirconium-based metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) that exhibit exceptional chemical stability; these are investigated for gas storage, separation and catalysis.

- Surface coatings of zirconium oxide and zirconium nitride for wear resistance in cutting tools and medical devices.

- Resilient thermal barrier coatings and composite ceramics for aerospace engines and hypersonic vehicles, leveraging the high-temperature stability of zirconia phases.

In catalysis, while zirconium itself is not the most active transition metal, its stable oxides provide acid–base surface sites and high-temperature resilience, useful in reforming, hydrodeoxygenation and as supports for active catalytic phases.

Environmental, safety and economic considerations

Mining and processing zirconium-bearing sands can have substantial environmental impacts, especially when dredging coastal or offshore deposits. Proper reclamation, dust control and wastewater treatment are necessary to minimize ecological harm. The chemical processing of zircon to produce ZrCl4 and subsequent Kroll reductions uses chlorination and reactive metals, presenting occupational safety hazards if not carefully managed.

Metallic zirconium in fine particulate or powder form is pyrophoric and can ignite spontaneously in air; proper controls are required in manufacturing and storage. Zirconia ceramics are generally inert and safe, which is one reason they are favored in biomedical applications.

Economically, demand for zirconium is tied to several industries: nuclear energy (for alloys), ceramics and refractories (for zircon and zirconia), and jewelry (for both natural zircon and synthetic cubic zirconia). Market prices fluctuate with mining output, geopolitical factors affecting supply chains and the pace of technological adoption in areas such as SOFCs and advanced reactors.

Interesting facts and lesser-known aspects

- Zircon crystals are used in geochronology. Certain zircons can retain uranium and exclude lead when they form, allowing precise uranium–lead dating and giving insights into Earth’s early crust formation.

- Because zircon resists chemical and physical weathering, detrital zircons found in sedimentary rocks can be billions of years old and are critical in studying the planet’s ancient history.

- The close similarity between zirconium and hafnium originates in their electron configurations. Despite chemical likeness, their nuclear properties differ sharply, which is why separating them is essential for nuclear applications.

- Modern diamond simulants called cubic zirconia were first synthesized in the 1970s, offering a cheap, optically brilliant alternative to diamonds and bringing the name “zircon” and “zirconia” into popular culture—often causing confusion between the natural gemstone and the synthetic material.

Practical tips for handling and choosing materials

If selecting a zirconium-containing material for an application, consider the following:

- For high-temperature or corrosive environments, evaluate zirconia ceramics and stabilized forms for thermal shock resistance and chemical stability.

- In nuclear or neutron-sensitive contexts, confirm hafnium specifications and the production history to ensure acceptable neutron cross-section properties.

- For biomedical uses, assess surface finish, grain size and documented biocompatibility of dental zirconia products.

- When buying gemstones, know the difference between natural zircon and synthetic cubic zirconia—both have aesthetic value but different physical and market characteristics.

Concluding observations

From ancient gemstones to cutting-edge ceramics and critical reactor components, zirconium and its compounds play diverse and indispensable roles in modern technology. Its ability to form robust oxides, tolerate high temperatures and—when properly processed—offer low neutron absorption has positioned zirconium as a material of both traditional and strategic importance. As new materials science techniques evolve, zirconium’s family of alloys, oxides and composites will likely find even more specialized uses across energy, medical and advanced manufacturing sectors.