The role of graphite in next-generation energy storage spans from the well-established anode material in commercial lithium-ion batteries to emerging functions in solid-state cells, sodium-ion systems, and advanced supercapacitors. As researchers and industry push toward higher performance, faster charging, and more sustainable supply chains, graphite remains central because of its unique combination of layered structure, electrical conductivity, chemical stability, and relatively low cost. This article examines graphite’s material properties, its place in current battery architectures, ongoing engineering innovations to extend its capabilities, and the environmental and supply-chain considerations that will determine its role in the energy transition.

Graphite fundamentals and material properties

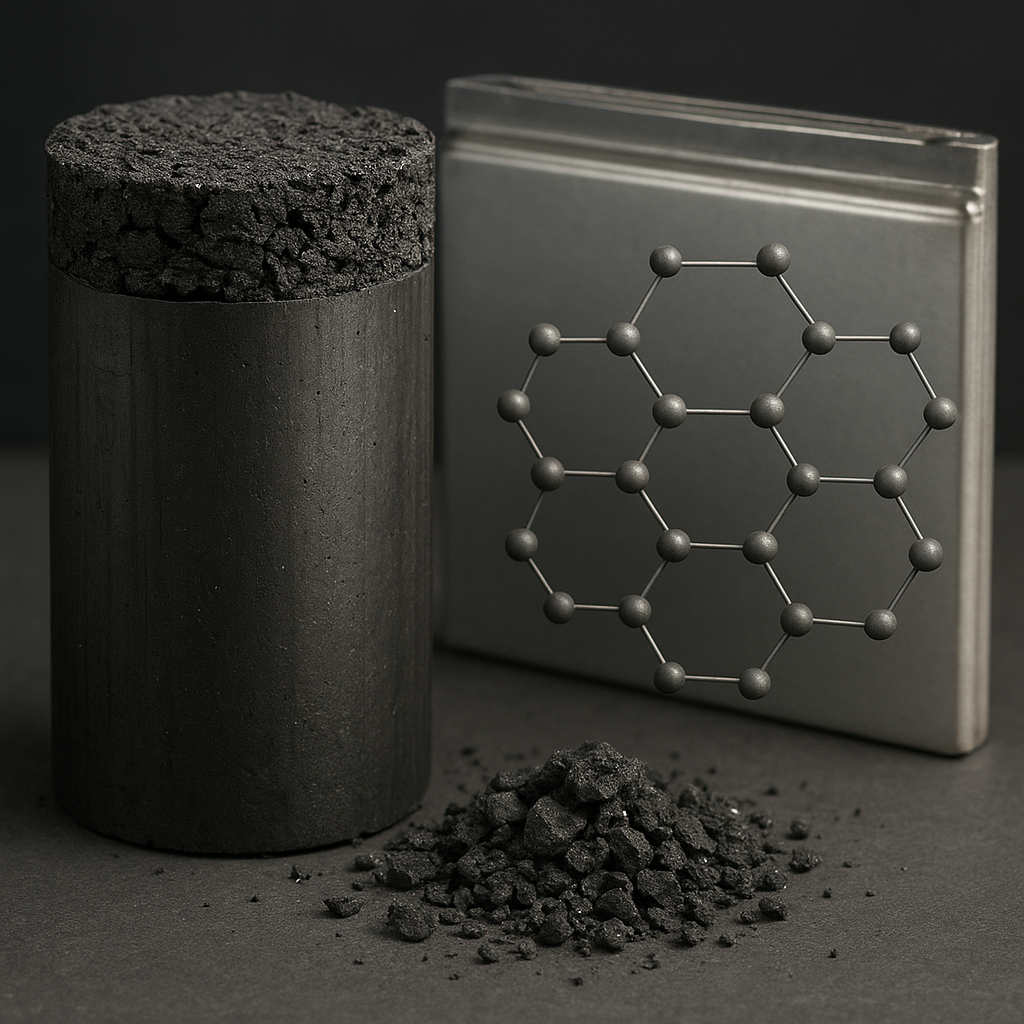

Graphite is a crystalline form of carbon in which atoms are arranged in hexagonal layers called graphene planes. The weak van der Waals forces between these planes allow ions like lithium to intercalate between layers, enabling reversible charge storage. Key intrinsic properties that make graphite attractive for energy storage include high in-plane electrical and thermal conductivity, mechanical flexibility of layers, chemical inertness in many electrolyte environments, and a structure that supports stable formation of a solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) under controlled conditions. Natural graphite and synthetic graphite differ in impurity content, particle morphology, and cost; both classes have trade-offs that influence performance metrics such as initial coulombic efficiency, rate capability, and cyclability.

Theoretical capacity of graphite for lithium intercalation is limited by the LiC6 stoichiometry, corresponding to ~372 mAh g−1. While this value is modest compared with high-capacity materials such as silicon, graphite’s practical significance stems from its exceptional cyclability and low-voltage operation, which help ensure safety and energy efficiency in full cells. Graphite’s layered structure also allows engineering interventions—such as surface coatings, particle size control, and heteroatom doping—that can optimize ion diffusion pathways and mitigate degradation mechanisms like particle cracking and excessive SEI growth.

Graphite in current battery technologies

Lithium-ion anodes

Commercial lithium-ion batteries overwhelmingly use graphite as the dominant anode material. Its reliable performance across thousands of cycles in well-designed cells has enabled widespread deployment in consumer electronics, electric vehicles (EVs), and grid-scale storage. Graphite anodes are typically combined with binders, conductive additives, and tailored electrolytes to form composite electrodes. Achieving high energy density requires designs that maximize electrode density and minimize inactive components, while still accommodating volumetric changes and maintaining ion transport. Manufacturers also consider the balance between natural and synthetic graphite: natural graphite offers cost advantages and favorable particle morphology for packing density, whereas synthetic graphite can be engineered for specific particle shapes, purities, and surface chemistries that improve fast-charge performance and initial coulombic efficiency.

Beyond lithium: sodium-ion and alternative systems

Graphite historically struggles to intercalate sodium ions effectively because sodium’s larger ionic radius does not fit the graphite interlayer spacing as comfortably as lithium. Nevertheless, research has demonstrated that modified graphitic structures—expanded graphite, co-intercalation compounds, and graphite intercalation compounds (GICs) with engineered solvents—can host sodium to some extent, opening pathways for sodium-ion anodes that could leverage graphite-like materials. For emerging systems such as dual-ion and potassium-ion technologies, graphite and related carbonaceous materials continue to be evaluated for their ability to reversibly store ions at acceptable voltages and with long-term stability.

Supercapacitors and conductive additives

Graphite and graphitic derivatives (e.g., graphene, expanded graphite) serve important roles in electrochemical capacitors. While activated carbons offer very high surface area for electric double-layer capacitance, graphitic forms provide superior electrical conductivity and structural robustness, making them excellent current collectors and conductive additives. In hybrid devices that combine faradaic and double-layer mechanisms, graphitic materials can improve power density and cycle life. Additionally, graphite’s thermal conductivity is beneficial for thermal management in high-power applications.

Engineering strategies and innovations

To extend graphite’s utility in next-generation energy storage, researchers and industrial developers are pursuing multiple engineering strategies. These efforts aim to overcome limitations such as modest specific capacity and rate-dependent losses, while preserving graphite’s strengths in stability and scalability.

- Surface coatings and functionalization: Applying thin, conformal coatings (e.g., carbon, oxides, polymers) can stabilize the interface between graphite and electrolyte, suppress excessive SEI formation, and improve initial coulombic efficiency. Functional groups introduced on the surface can tune wettability and electrolyte decomposition pathways.

- Particle size and morphology control: Nanoscale engineering of graphite particles—creating smaller particles, platelets, or spheroidalized natural graphite—enhances ion-accessible surface area and shortens diffusion paths, improving rate capability. However, this must be balanced against increased surface reactivity and greater SEI formation.

- Graphite composites: Combining graphite with high-capacity materials such as silicon, tin, or transition-metal oxides yields hybrid anodes that pair graphite’s stability with the high specific capacity of the alloying component. Composite designs mitigate the volumetric expansion of silicon by embedding it in a conductive graphite matrix, improving mechanical resilience and cycle life.

- Nano- and micro-structuring: Constructing hierarchical architectures—such as porous graphite scaffolds or coating graphene layers onto graphite flakes—can optimize both ion transport and electrode density. These structures can be tailored to accommodate fast charge-discharge cycles without excessive degradation.

- Prelithiation and electrode conditioning: To address initial irreversible capacity loss associated with SEI formation, industrial processes often apply prelithiation techniques that compensate for lithium consumption and improve early-cycle efficiency. Graphite electrodes benefit from optimized formation protocols and electrolyte additives that form robust SEI layers.

Innovations also include exploring graphite derivatives such as turbostratic carbon, expanded graphite, and few-layer graphene to harness unique interlayer spacing or surface properties. For solid-state batteries, interface engineering between graphite and solid electrolytes is a critical challenge: maintaining intimate contact while preventing undesired interfacial reactions requires tailored surface chemistries and compliant buffer layers.

Performance challenges and mitigation

Despite many advantages, graphite faces several performance challenges in next-generation applications. Key issues include limited theoretical capacity relative to alloying anodes, rate limitations due to diffusion in bulk particles, sensitivity to electrolyte composition, and dendrite-related risks when paired with lithium-metal counter electrodes. Strategies to mitigate these problems include composite anodes that blend graphite with silicon or tin, which increase overall capacity while preserving the stable potential window of graphite; electrolyte additives that form flexible SEI films to tolerate volume changes; and electrode designs that balance particle size distribution for both energy density and power capability.

Fast charging, a priority for EV adoption, exposes graphite to accelerated SEI growth and potential lithium plating when lithium ions cannot intercalate quickly enough. Addressing this requires simultaneous optimization of electrode microstructure, electrolyte formulation (including high-concentration or localized high-concentration electrolytes), and thermal management. Advanced diagnostics—such as in situ microscopy and operando spectroscopy—help developers understand failure modes at the microscopic scale and tailor mitigation strategies.

Supply chain, sustainability, and recycling

Economic and environmental considerations will shape graphite’s role in large-scale energy storage deployment. Natural graphite mining is concentrated geographically, and feedstock quality varies; synthetic graphite production, while more uniform, is energy-intensive. Lifecycle assessments compare trade-offs between mining impacts, processing energy, and long-term performance benefits. Increasingly, companies are investing in traceability and responsible sourcing practices to reduce environmental and social risks associated with raw material extraction.

Recycling represents a critical lever to improve sustainability and secure graphite supply. End-of-life battery processing can recover graphitic carbon, although separating graphite from other electrode components and restoring its electrochemical quality at scale remains a technical and economic challenge. Advances in hydrometallurgical and pyro-metallurgical recycling, along with direct electrode regeneration methods, are improving recovery rates and reducing the need for virgin material. Circular economy approaches that prioritize reuse, remanufacturing, and material recovery will be central to maintaining supply resilience and lowering lifecycle emissions.

Industrial scaling and economic considerations

Cost drivers for graphite include raw material availability, processing complexity, and quality control for battery-grade specifications. Synthetic graphite offers tight control over impurities and particle morphology but requires significant energy input, often making it more expensive than natural graphite. Market dynamics—driven by demand from EVs, grid storage, and portable electronics—affect prices and investment in new production capacity. Policy interventions, such as incentives for domestic processing or restrictions on unsustainable mining practices, can influence where and how graphite is sourced and processed.

For manufacturers, electrode fabrication yield and consistency are paramount. Graphite’s compatibility with existing roll-to-roll coating processes and well-understood slurry formulations gives it a manufacturing advantage compared with newer materials that require process overhauls. Nonetheless, incorporating advanced graphite composites or nanoscale modifications at scale demands careful control of batch-to-batch variability and worker safety protocols to handle fine powders.

Future prospects: integration with emerging chemistries

Looking ahead, graphite will likely remain an essential component across a range of battery chemistries, though its form and function may diversify. Potential trajectories include:

- Graphite as a stable host in hybrid anodes, pairing with high-capacity alloys to achieve balanced energy and cycle life.

- Engineered graphitic interfaces in solid-state batteries, where compliant graphite interlayers could enable safer and higher-energy cells by mitigating interface resistance and mechanical mismatch.

- Functionalized graphite in fast-charging architectures, where surface engineering reduces lithium plating and supports rapid ion transport.

- Expanded or modified graphite enabling sodium and other post-lithium systems to leverage graphitic conductivity and structure while accommodating larger ions.

Advances in computational materials science and high-throughput experimentation are accelerating discovery of graphite modifications and composites tailored to specific performance objectives. Coupled with improved recycling technologies and more sustainable production methods, these innovations will determine whether graphite maintains a central role or is gradually supplanted in particular niche applications. The balance of performance, cost-effectiveness, and environmental footprint will be decisive as the energy storage landscape evolves.

Research directions and priorities

Key research priorities include: understanding interfacial chemistry at atomic scales to design SEI layers that are both protective and ionically conductive; developing scalable composite manufacturing that integrates high-capacity materials without sacrificing lifetime; designing electrolytes and additives specifically for graphite-based fast-charge and solid-state systems; and improving direct recycling processes to recover battery-grade graphite with minimal environmental impact. Collaboration between academia, industry, and policy makers will be necessary to translate laboratory innovations into commercially viable, safe, and sustainable products.

Concluding remarks

Graphite’s combination of layered structure, electronic conductivity, manufacturability, and relative affordability positions it as a linchpin in the near-term evolution of energy storage technologies. While not without limitations—particularly in capacity and fast-charge robustness—graphite’s adaptability through coatings, composites, and structural engineering continues to extend its relevance. Decisions made today about sourcing, processing, and recycling graphite will have long-term implications for the cost, performance, and sustainability of next-generation batteries. Continued innovation across materials science, electrode engineering, and circular economy practices will be essential to fully realize graphite’s potential in the global energy transition.