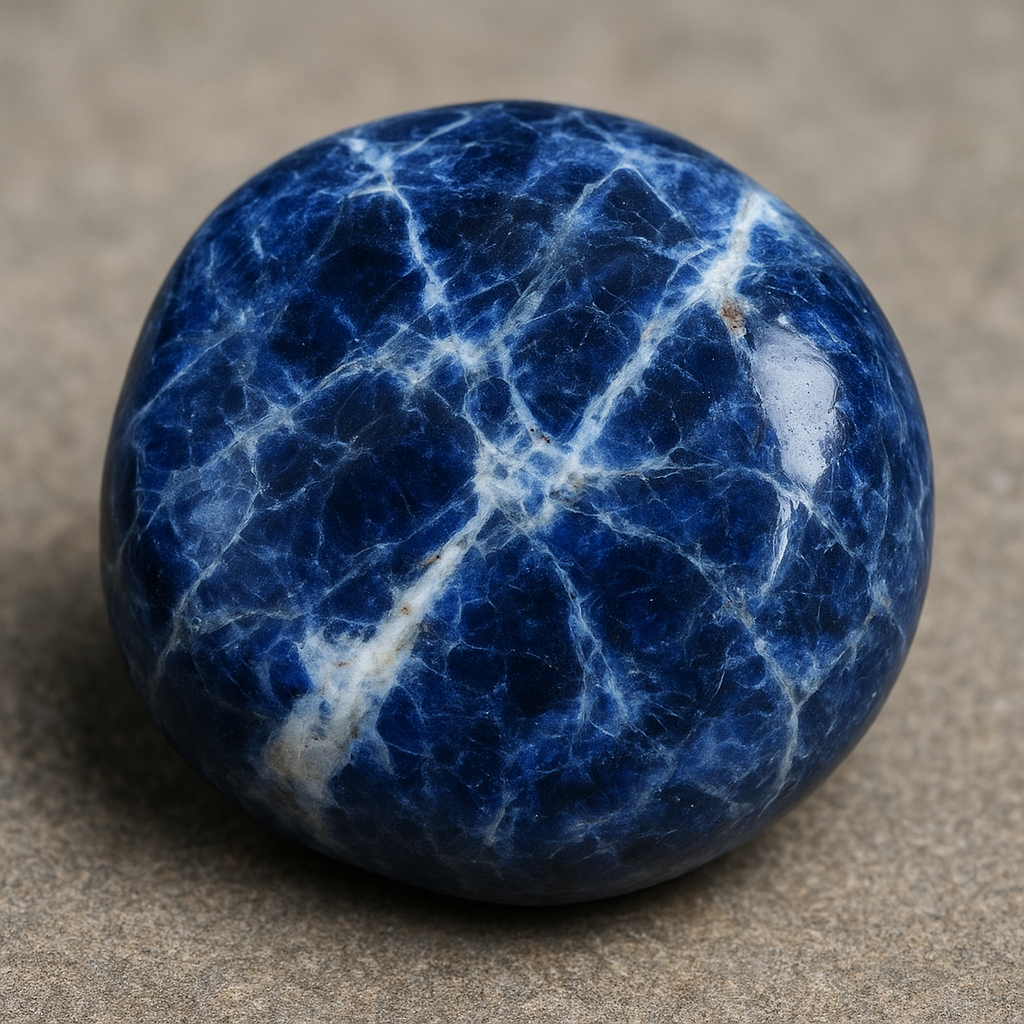

Sodalite is a strikingly blue stone that has captured the interest of mineralogists, lapidaries and collectors for two centuries. Its deep hues, often punctuated by white calcite veins, make it an attractive material for jewelry and ornamental uses, while its mineralogical characteristics provide insight into the chemistry and formation of silica-undersaturated igneous systems. In the text below you will find an overview of its geology, main occurrences, physical and optical properties, practical applications, care and lapidary considerations, as well as some cultural and scientific aspects that make sodalite an enduring subject of interest.

Geology, Chemistry and Formation

Sodalite belongs to the feldspathoid family of minerals, forming in environments where silica is relatively deficient. Its idealized chemical formula is Na8(Al6Si6O24)Cl2, a framework of aluminosilicate cages that incorporate sodium and chloride ions. This structural arrangement places sodalite among a group of framework silicates notable for their open cages and channels; those frameworks inspire research in materials science because they resemble structures seen in zeolites and related porous materials.

Typical geological settings for sodalite include:

- Intrusive silica-undersaturated alkalic igneous rocks, such as nepheline syenites and related pegmatites.

- Metasomatic zones where fluids alter existing rocks under sodium- and chloride-rich conditions.

- Rarely, as an accessory mineral in hydrothermal vein systems with unusual chemistry.

Formation mechanisms

Sodalite commonly forms during the late stages of crystallization of alkalic magmas that lack enough silica to form feldspar or quartz. The presence of chlorine in the melt favors stabilization of sodalite and related minerals. In some complexes, sodalite associates with minerals such as nepheline, cancrinite, aegirine, and feldspathoids, reflecting the overall low-silica, sodium-rich character of the host.

Major Localities and Geological Environments

Occurrences of sodalite range from small vein or pocket deposits to world-famous massif-type alkaline complexes. Notable localities include:

- Bancroft and other Ontario localities (Canada) — popular sources of attractive blue sodalite used by lapidaries.

- Mont Saint-Hilaire (Quebec, Canada) — a classic site with many rare associated minerals and attractive specimens.

- Ilímaussaq complex (Greenland) — produces sodalite and related feldspathoids; some varieties here show special optical behavior.

- Kola Peninsula (Russia) — part of the alkaline complexes that yield sodalite and a suite of rare minerals.

- Brazil and Bolivia — provide gem-quality material used in jewelry and decorative stone.

- Namibia and India — additional commercial and collector sources.

- United States — local occurrences include small deposits in states with alkalic intrusives; material from some sites is used locally for ornamental stone.

Within these environments, sodalite may be found as coarse-grained masses, as vug-filling crystals, or intergrown with other feldspathoids and associated minerals. When present in decorative rock such as lapidary slabs, it is often mixed with calcite, which gives the material its characteristic white veining.

Physical and Optical Properties — How to Identify Sodalite

Sodalite is generally recognized by a combination of color, physical hardness, and association. Key properties include:

- Color: typically deep royal to rich blue, but also gray, greenish or violet tones; often intergrown with white calcite veins.

- Luster: vitreous to greasy on fresh surfaces.

- Hardness: about 5.5–6 on the Mohs scale, making it softer than many common gem materials.

- Cleavage and fracture: poor to indistinct cleavage, conchoidal to uneven fracture.

- Streak: white.

- Specific gravity: around 2.2–2.3.

Optically, sodalite is isotropic under polarized light in thin section because it is a cubic mineral—this can help distinguish it from anisotropic blue silicates. Some sodalite specimens show strong fluorescence—particularly in varieties associated with certain impurities or inclusions, displaying orange or red fluorescence under shortwave UV. A remarkable variety, known as hackmanite, exhibits reversible photochromism (color change) or tenebrescence, where exposure to UV or sunlight produces a color change that fades in the dark. Hackmanite specimens are prized by collectors for this dynamic optical behavior.

Uses and Applications

Although sodalite is not as hard as mainstream gem materials like sapphire or quartz, its unique color and patterning have led to a number of uses:

Jewelry and Lapidary

- Cabochons: Sodalite is commonly cut as cabochons for rings, pendants and earrings.

- Beads and inlay: polished beads and inlays in ornamental objects and mosaic work are popular.

- Carvings and sculptures: large polished masses are carved into decorative items and figurines.

Because of its moderate hardness and relative brittleness, sodalite is best used in jewelry that is not subject to rough wear—pendants, earrings and brooches are safer choices than rings for everyday wear. In lapidary, sodalite polishes to a good luster and mixes attractively with other stones, especially white calcite, producing striking contrasts.

Ornamental and Architectural Use

When cut as slabs, sodalite provides an attractive facing stone for interiors, tabletops and decorative panels. Its dramatic blue often lends a luxurious feeling when used thoughtfully. However, because of its softness and sensitivity to acids, sodalite is less suitable for high-wear surfaces such as kitchen countertops unless properly sealed and maintained.

Collecting and Museum Specimens

Specimens of sodalite, especially large, well-crystallized or hackmanite examples that demonstrate tenebrescence and fluorescence, are coveted by mineral collectors and museums. Rarity of large gem-quality blocks from certain localities can make specific pieces valuable in the collector market.

Lapidary Techniques, Care and Treatments

Working with sodalite requires awareness of its physical limits. Lapidary considerations include:

- Cutting and shaping: use moderate speeds and ample cooling to prevent fracturing. Diamond tools are preferred for shaping and slicing.

- Polishing: standard diamond pastes and cerium oxide produce high polish; avoid overworking edges that can chip.

- Stabilization: porous specimens or those with fractures are sometimes impregnated with resins to improve durability and appearance; such treatments should be disclosed in commercial contexts.

Care instructions for sodalite jewelry and objects:

- Clean with warm soapy water and a soft brush—avoid steam cleaners and ultrasonic cleaners if the piece is treated or has inclusions.

- Protect from prolonged exposure to harsh acids, household chemicals or intense sunlight (especially for hackmanite varieties prone to fading or color change).

- Store separately to prevent scratching by harder gemstones.

Varieties, Look-alikes and Identification Challenges

Sodalite can be confused with other blue stones. Understanding distinguishing features helps:

- Blue lapis lazuli (primarily lazurite) — lapis typically contains pyrite flecks and is deeper, often more opaque; lapis is historically prized and chemically distinct though related through the sodalite mineral group.

- Azurite and Lapis Lazuli — these are typically deeper and have different streak and hardness characteristics.

- Blue calcite and dyed howlite — these may mimic the blue color but differ in hardness and reaction to acids, and some are clearly man-made dyes on porous hosts.

Testing with simple tools—streak, hardness, and observation under UV—combined with knowledge of matrix and locality can usually separate sodalite from look-alikes. For definitive identification, X-ray diffraction or chemical analysis will confirm the framework structure and chlorine content typical of sodalite.

Cultural, Historical and Metaphysical Contexts

Although not as anciently cited as lapis lazuli, sodalite has gained cultural traction in modern times. The stone’s deep blue tones have associated it with the throat and third-eye chakra in metaphysical circles, where practitioners attribute properties such as enhanced communication, mental clarity and emotional balance. These uses are spiritual and anecdotal rather than scientifically validated, but they have contributed significantly to sodalite’s popularity among crystal enthusiasts.

Historically, sodalite was first described in 1811 following discoveries in Greenland; its name reflects its sodium content. Since the 19th and 20th centuries it has been used as an ornamental stone and has occasionally been used in architectural settings where its dramatic color complements design schemes.

Scientific and Industrial Relevance

Beyond its ornamental appeal, sodalite’s structural motif is of interest in materials science. The sodalite cage—a polyhedral cavity within the aluminosilicate framework—serves as a model for porous materials that can host ions or molecules. This structural type inspires research on ion exchange, gas sorption and catalysts in synthetic analogs and zeolite-like materials.

In addition, the study of sodalite and related feldspathoids provides geoscientists with indicators of magmatic evolution. Sodalite’s presence signals silica-undersaturated, volatile-rich melts and helps reconstruct magmatic conditions such as chlorine and sodium activity during crystallization. Such information is valuable for understanding rare-metal and rare-earth element distribution in alkaline complexes.

Collecting, Value and Market Considerations

The market value of sodalite depends largely on color uniformity, intensity of blue, size, absence of cracks and the presence of unique features such as tenebrescence or striking matrices. High-quality sodalite cabochons and carved items can fetch good prices in the lapidary market, while large architectural slabs of attractive material are valued by interior designers. Collectors particularly prize hackmanite specimens, vivid fluorescent material and crystals from historically significant localities.

When buying sodalite:

- Seek reputable sellers who disclose treatments such as stabilization or dyeing.

- Ask about locality and whether the specimen displays fluorescence or other notable optical properties.

- Compare pieces visually for color saturation and matrix contrast—white calcite veins can be complementary, but excessive veining lowers gem-grade value.

Interesting Facts and Lesser-Known Aspects

Some features that enthusiasts and professionals find particularly intriguing:

- Certain sodalite occurrences show strong orange or red fluorescence under shortwave UV, creating spectacular display specimens under lights used by collectors and museums.

- Hackmanite’s reversible color response to light makes it a natural “photochromic” mineral; specimens can be demonstratively switched between different hues for educational displays.

- The sodalite structural family links mineralogy and materials science — the same cage motifs are exploited in synthetic porous materials for adsorption and catalysis research.

- Although sodalite is durable enough for many ornamental uses, its sensitivity to acids and moderate hardness means it occupies a niche between purely decorative stones and daily-wear gem materials—this gives designers and lapidaries creative challenges and opportunities.

Final Notes on Appreciation and Practical Use

For anyone drawn to deep blue stones, sodalite offers a compelling combination of aesthetic appeal, geological story and practical utility. Whether displayed as a polished slab in an interior design context, set into a pendant, or kept in a mineral collection for its optical oddities, sodalite rewards a closer look. Its chemistry and structure make it a mineralogical bridge between natural history and modern materials research, ensuring that it remains relevant both to collectors and to scientists exploring porous aluminosilicate frameworks.