Sapphire is one of the most admired and versatile gemstones in both history and modern technology. Known for its striking colors, remarkable physical properties, and wide range of uses, this mineral carries a legacy that spans royalty, science, and industry. The following article explores its geology, cultural significance, industrial applications, and the scientific developments that keep sapphire at the intersection of art and innovation.

What Sapphire Is: Mineralogy and Color

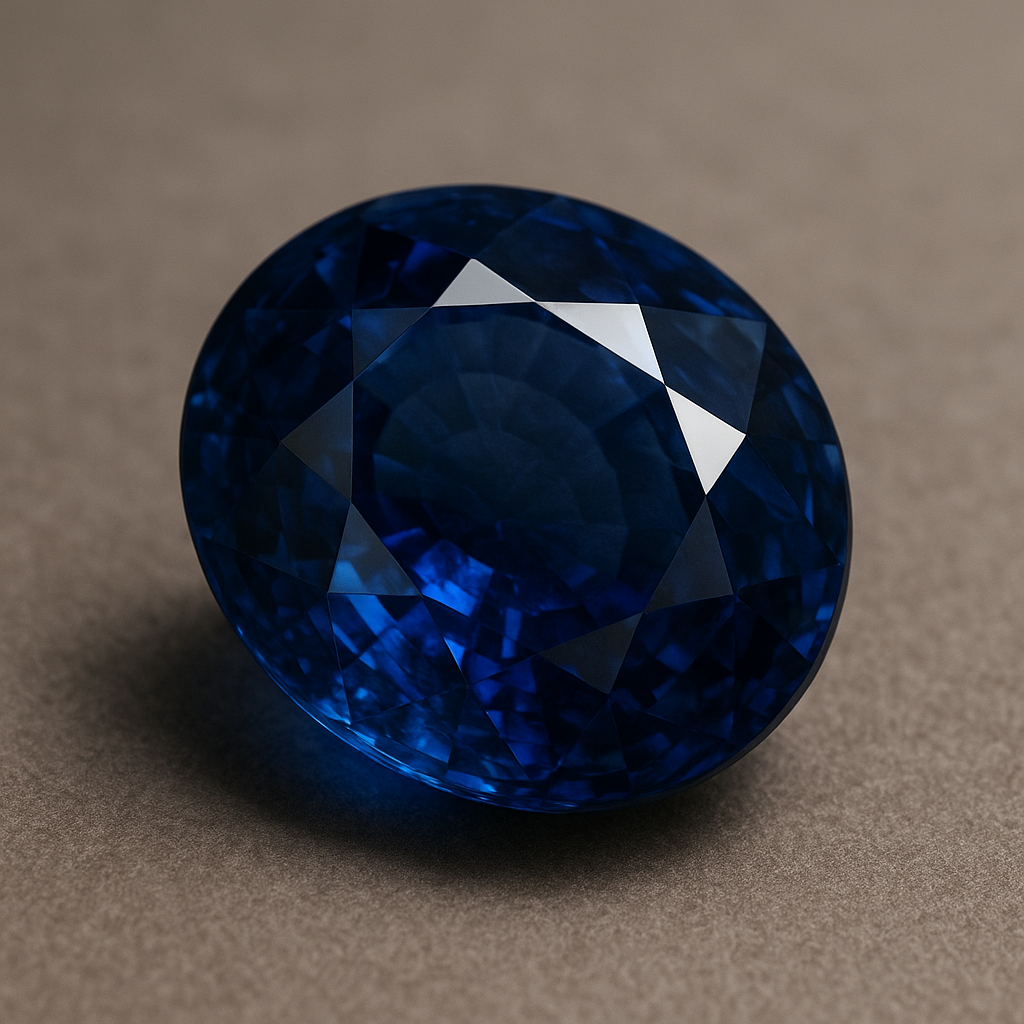

Sapphire is a variety of the mineral corundum, an aluminum oxide (Al2O3) that forms in crystalline structures characterized by excellent hardness and chemical stability. Pure corundum is colorless, but trace elements such as iron, titanium, chromium, vanadium, and magnesium introduce a spectrum of hues. While the popular image of sapphire emphasizes deep blue stones, sapphires occur in almost every color except red; the red variety is classified as ruby.

The crystalline structure of corundum is trigonal, and its physical properties explain much of sapphire’s value. On the Mohs scale of mineral hardness, sapphire ranks at 9, second only to diamond. This exceptional hardness contributes to its resistance to scratches and wear, making sapphire prized in both jewelry and demanding technical applications. Its refractive index, typically around 1.76–1.77, gives polished stones a desirable brilliance and depth.

Where Sapphire Is Found: Geology and Major Localities

Sapphire forms in metamorphic and igneous environments where aluminum-rich rocks undergo high temperatures and pressures. There are several primary geological settings:

- Metamorphic deposits in schists and marbles, where pre-existing minerals recrystallize.

- Pegmatitic and igneous environments, where slow cooling allows large crystals to form.

- Alluvial deposits, where weathering and erosion concentrate durable grains in river gravels.

Important sapphire localities include classical and modern sources. Sri Lanka has produced famed Ceylon sapphires for centuries, known for their bright, velvety blues and lighter tones. The mountainous region of Kashmir (in the Indian subcontinent) yielded some of the most sought-after royal blue sapphires, prized for their intense, velvety color and velour-like appearance. Other notable sources are Myanmar (Burma), Madagascar, Thailand, Australia, Cambodia, Vietnam, Tanzania, Kenya, Nigeria, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the U.S. state of Montana.

Alluvial deposits often provide sizable gem-quality crystals with rounded shapes, while primary host-rock occurrences can yield large euhedral crystals suitable for lapidary work and industrial use. Each deposit tends to have distinct color profiles and inclusion types, which gemologists use to help determine origin—an important factor for collectors and high-end buyers.

Gemological Varieties and Notable Examples

Beyond the common blue, sapphires occur in a rainbow of colors and special optical effects:

- Padparadscha: A rare and highly prized pinkish-orange variety; the name derives from the Sinhalese word for lotus blossom.

- Fancy sapphires: Sapphires in shades of yellow, green, purple, and pink, each with unique market demand.

- Star sapphires: These display asterism—an optical star caused by oriented needle-like inclusions (rutile)—and are typically cut as cabochons.

Famous sapphires such as the Star of India and the Logan Sapphire have captivated the public and highlight the gemstone’s cultural prestige. Collectors prize stones for color, clarity, cut, size, and provenance; Kashmir sapphires and certain Ceylon sapphires often command premium prices because of their rarity and distinctive color quality.

Synthetic Sapphire: Methods and Identification

Technological demand and the desire for consistent gem material led to the development of synthetic sapphire. The first commercially successful process was the Verneuil flame-fusion method, introduced in the early 20th century, producing large, relatively inexpensive crystals. Other methods include the Czochralski pulling, hydrothermal synthesis, and the Bridgman technique. Synthetic sapphires can be produced in a variety of colors and in large boules that are useful for both gem and industrial purposes.

Gemologists differentiate natural from synthetic stones through microscopic examination, spectroscopy, and advanced analytical techniques. Synthetic stones often show distinctive growth patterns, gas bubbles, or flux inclusions depending on the production method. Heat treatment and diffusion treatments—common practices to enhance color and clarity—further complicate identification, making professional certification important for high-value purchases.

Applications Beyond Jewelry: Industrial and Scientific Uses

Sapphire’s combination of durability, optical clarity, and thermal stability makes it invaluable outside the world of adornment. Major industrial and scientific applications include:

- Optical windows and lenses: Sapphire is transparent across much of the visible and near-infrared spectrum, making it suitable for high-performance windows in harsh environments, camera lenses, and sensor covers.

- Substrates for LEDs: Large single-crystal sapphire wafers serve as substrates for gallium nitride (GaN) epitaxy in the production of light-emitting diodes LEDs. The compatibility of lattice structures and thermal properties makes sapphire an industry-standard substrate.

- Watch crystals and electronic displays: Synthetic sapphire is used for scratch-resistant watch faces and protective covers for high-end smartphone camera modules and precision instruments.

- Laser media: When doped with titanium, sapphire becomes Ti:sapphire, an important gain medium for tunable ultrafast lasers, widely used in research, medicine, and spectroscopy.

- Scientific optics and high-pressure experiments: Sapphire’s hardness and pressure resistance allow it to be fashioned into anvils and viewports for high-pressure research.

The industrial demand for synthetic sapphire has grown substantially. Manufacturers value the ability to produce large, pure boules and wafers tailored to technical specifications, enabling mass production of LED substrates and rugged optical components.

Cutting, Treatment, and Grading

Gem cutters must consider a stone’s color distribution and inclusions when planning cuts. Unlike diamonds where brilliance is paramount, sapphire cutting often prioritizes color saturation and face-up appearance. Faceted cuts enhance light return in transparent stones; cabochons preserve color and show phenomena like asterism.

Common treatments include:

- Heat treatment: Widely accepted in the trade, heat can remove inclusions, enhance color, and improve clarity. Heated sapphires are usually stable and long-lasting.

- Diffusion treatment: Involves introducing elements like beryllium into the near-surface to alter color. Diffusion-treated stones can have intense surface color but may not be accepted as “natural” color by some standards.

- Dyeing and fracture-filling: Less accepted techniques used to mask imperfections; these treatments can affect durability and value and should be disclosed to buyers.

Grading considers color (hue, tone, saturation), clarity, cut, and carat weight. Color remains the most significant factor; the finest sapphires display a rich, velvety blue without appearing too dark. Padparadscha and untreated Kashmir or Ceylon stones often receive special recognition in the marketplace.

Historical and Cultural Significance

Sapphires have adorned religious and royal objects for millennia. They symbolized virtues such as wisdom, nobility, and protection. Clergy and royalty often wore sapphire-set rings and reliquaries, believing the stones could bring divine favor or guard against harm. In more modern times, sapphires have become symbols of romance and commitment; the famous engagement ring featuring a sapphire worn by Princess Diana and later Kate Middleton helped popularize colored gemstones in engagement jewelry.

Folklore attributes many powers to sapphire—clarity of thought, protection from envy, and spiritual insight—and many cultures have woven the gem’s deep colors into their myths and rituals. While modern buyers are often motivated by aesthetic and investment considerations, cultural associations still influence demand and the perceived prestige of certain stones.

Environmental and Ethical Considerations

Like many mined resources, sapphire extraction can have environmental and social impacts. Alluvial mining can lead to landscape alteration, sedimentation of waterways, and deforestation if not managed responsibly. Labor issues, including unfair wages and unsafe conditions, have been reported in some producing regions.

Efforts to improve transparency and sustainability include:

- Responsible sourcing initiatives and due-diligence frameworks applied by major buyers and jewelry brands.

- Certification and origin documentation to attest to ethical supply chains and legal compliance.

- Growth in demand for traceable, ethically mined or laboratory-grown sapphires where environmental footprint and working conditions can be more strictly controlled.

Consumers increasingly expect documentation and responsible pedigree for precious stones. This trend encourages producers and retailers to adopt better practices and to disclose treatment histories and origin when possible.

Care, Maintenance, and Buying Tips

Owing to their high hardness, sapphires are relatively easy to care for, but certain precautions help ensure longevity:

- Clean with mild detergent, warm water, and a soft brush; avoid ultrasonic cleaners if the stone has fracture fillings or is heavily included.

- Remove jewelry during heavy manual labor to protect settings and prevent knocks that could chip the gem or its mounting.

- Store separately from other gemstones to prevent abrasion of softer stones and to avoid tangling chains.

When buying a sapphire, consider the following guidance:

- Request certificates from reputable gemological laboratories that detail origin (if known), treatments, and authenticity.

- Evaluate color under neutral lighting; color that looks good in one light may appear different in other environments.

- Decide between natural and synthetic based on priorities: natural stones carry historical and rarity value, while synthetic sapphires offer larger sizes and more consistent color at lower cost.

Scientific Frontiers and Future Directions

Sapphire continues to be significant in scientific research and advanced manufacturing. Innovations include high-quality sapphire wafers for next-generation optoelectronics, thin-film technologies using sapphire substrates, and exploration of sapphire’s mechanical properties in micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS). Research into color centers and quantum defects in sapphire is ongoing, with potential implications for quantum information science and advanced photonics.

The role of sapphire in laser technology—especially in Ti:sapphire devices—remains central to ultrafast optics. The combination of tunability, broad gain bandwidth, and high damage threshold helps sustain sapphire’s relevance in cutting-edge laboratories worldwide.

Interesting Facts and Lesser-known Uses

Several intriguing facts add to sapphire’s mystique and practical value:

- The famous “Star of India” is a 563-carat star sapphire that reflects the phenomenon of asterism and remains one of the largest known gem-quality stones of its type.

- Sapphire’s scratch resistance explains why some luxury watchmakers and optical component manufacturers favor it over glass.

- Industrial-grade sapphire—less attractive visually—finds important roles in military optics, aerospace windows, and high-pressure viewports.

- The term “sapphire” historically referred to several blue gemstones; modern gemology classifies stones more precisely, separating corundum-based sapphires from other blue minerals such as lapis lazuli or azurite.

Conclusion

Sapphire is more than a gemstone: it is a material that bridges beauty and technology. From the royal vaults of history to the cleanrooms of semiconductor manufacturing, the mineral embodies a rare combination of aesthetic allure and functional excellence. Whether sought after by collectors for its color and provenance, used by engineers for its optical and mechanical resilience, or synthesized in laboratories to meet modern demands, sapphire remains a stone whose significance continues to evolve.