Radium is one of the most intriguing elements in the history of science: prized for its mysterious glow, feared for its invisible power, and instrumental in shaping modern ideas about atomic structure and medical treatment. This article explores where radium is found, how it behaves chemically and physically, its historical discovery and uses, modern applications and risks, and the scientific and cultural stories that continue to surround this rare element.

What is Radium?

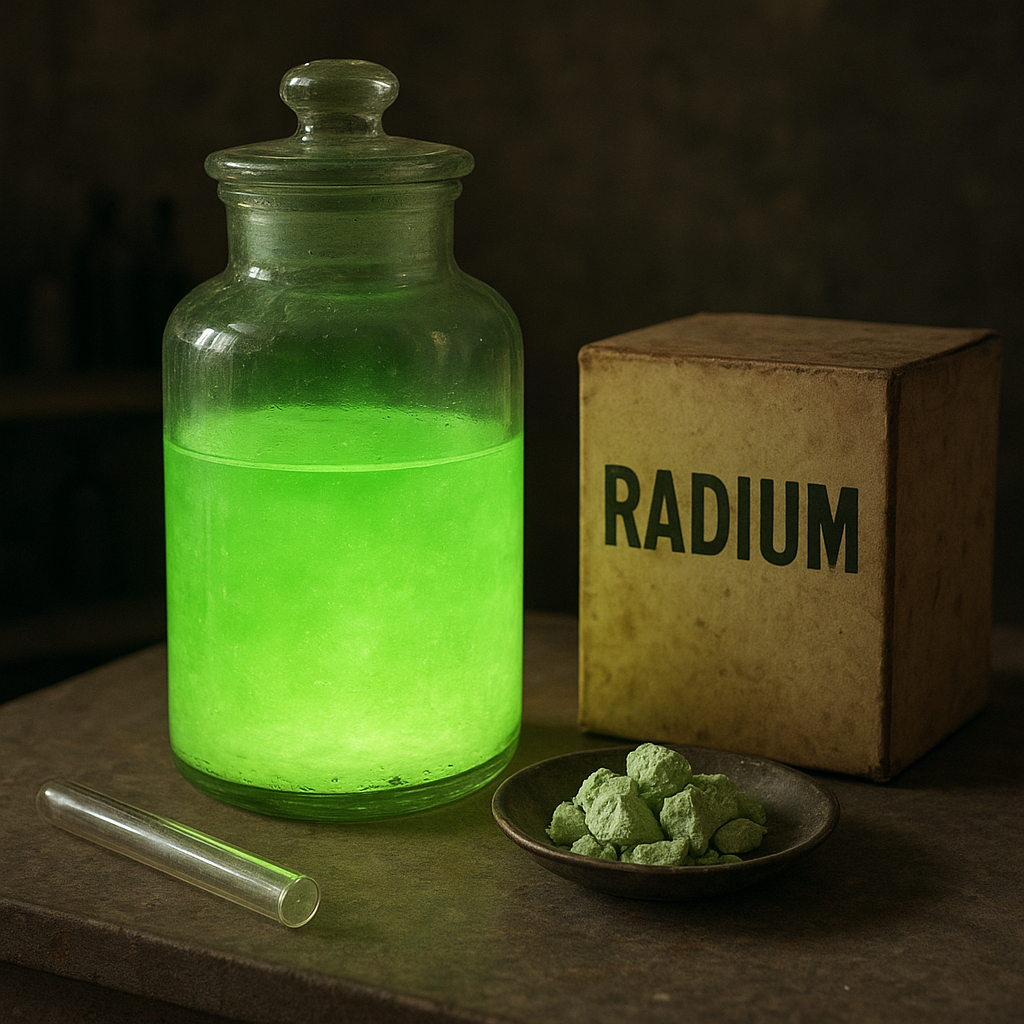

Radium is a highly radioactive alkaline earth metal that belongs to the same group as beryllium, magnesium, calcium, strontium, and barium. Discovered at the end of the 19th century, it became famous both for its intense radioactivity and for the faint blue-green glow of its salts. The symbol for radium is Ra and its atomic number is 88. In elemental form it is a silvery-white metal that tarnishes rapidly in air, but the properties that attracted public fascination and scientific investigation were its radioactive emissions and their ability to induce chemical and physiological effects.

Occurrence and Geology

Radium is not found freely in nature in significant amounts; it is a decay product of heavier radioactive elements and is located in trace amounts within certain uranium and thorium ores. Because it forms as part of natural radioactive decay series, radium is most commonly encountered in uranium-rich minerals such as pitchblende (uraninite), carnotite, and certain types of monazite and thorite.

Typical geological settings

- Granite and other igneous rocks that concentrate uranium and thorium.

- Veins and deposits associated with hydrothermal activity that mobilizes and precipitates uranium minerals.

- Sedimentary deposits where groundwater leaches uranium from host rocks and concentrates it into secondary minerals.

Because radium is chemically similar to barium, it often substitutes into barium-bearing minerals and can accumulate in scale inside water pipes and industrial equipment when groundwater with elevated uranium concentrations is processed. Another important environmental occurrence is radon, a noble gas produced by radium decay; radon can migrate through soils and accumulate in enclosed spaces such as basements, creating indoor air quality hazards.

History and Discovery

The discovery of radium is inseparably linked with the pioneering research of two scientists: Marie Curie and her husband Pierre Curie. In 1898, after careful separation and analysis of pitchblende residues, the Curies isolated a new, highly radioactive substance. They named the new element radium, from the Latin word for ray (radius), because of the rays it emitted. The isolation of radium salts and the subsequent measurement of their radioactivity were crucial to the development of nuclear physics and helped establish the concept that atoms could emit energy and particles.

Early fascination and uses

Following its discovery, radium was rapidly commercialized. It was used in luminous paint for clock dials, instrument panels, and watches. The aesthetic and apparent novelty of glowing products, combined with incomplete knowledge about long-term effects, led to widespread nonmedical applications. The tragic stories of dial painters who suffered devastating health effects later highlighted the dangers of unprotected exposure and were pivotal in occupational safety reform.

Physical and Chemical Properties

Chemically, radium behaves much like other alkaline earth metals, forming mostly +2 oxidation state compounds. Its chemistry is therefore dominated by ionic bonding and solutions of radium salts show characteristics similar to those of barium salts, though with some differences owing to relativistic and radiological effects.

- Atomic number: 88

- Standard atomic weight: approximately 226 (for the most stable isotope)

- Most stable isotope: 226Ra (half-life ~1600 years)

- Common oxidation state: +2

Physical properties include a relatively low melting point for a heavy metal and mechanical softness. Unlike many stable metals, radium samples are immediately notable for the ionizing emissions they produce; these emissions can ionize gases and cause chemical reactions in surrounding material. The familiar luminescent effect of certain radium compounds is not intrinsic to the metal itself but results from radiation exciting a phosphor in radium-based paints, producing a visible glow.

Radioactivity and Decay

The defining characteristic of radium is its radioactivity. The most common isotope, Ra-226, decays by emitting alpha particles, transforming slowly into radon gas and then through a series of subsequent decays into stable lead isotopes. The decay chain includes several short-lived daughters that emit further alpha and beta particles and gamma rays.

Types of emissions and their effects

- Alpha particles: heavy and highly ionizing but with very short penetration range. Harmful if radium or its daughters are ingested or inhaled.

- Beta particles: lighter, more penetrating than alpha but less ionizing; require shielding such as plastic or glass.

- Gamma rays: high-energy photons that are penetrating and require dense shielding (lead or concrete) to attenuate.

Because radium decays into radon, a mobile radioactive gas, it poses both solid-phase and airborne contamination risks. Radon concentration in indoor air remains an important public health concern in many regions where radium-bearing rocks are present.

Applications of Radium

Historically, radium saw a flurry of applications, but most have been abandoned due to safety concerns and the development of safer alternatives. Nevertheless, radium’s discovery paved the way for technologies and medical techniques that are still important today.

Historical and obsolete uses

- Radium-based luminous paints for watches and instrument dials (now replaced by tritium or photoluminescent compounds).

- Cosmetic and health quackery: radium was once sold in products ranging from health tonics to toothpaste—practices later recognized as dangerous.

Medical contribution and legacy

One of the most important applications historically was in therapy. Radium was used in early brachytherapy: sealed radium sources were placed near or within tumors to deliver ionizing radiation directly to cancerous tissue. Although modern radiotherapy uses more controllable and less radiotoxic isotopes (like cobalt-60, cesium-137 historically, and sealed sources of iridium-192 for some procedures) and medical linear accelerators, the principles established with radium—localized irradiation to destroy malignant cells—remain fundamental.

Scientific and industrial uses

- Standard sources for calibrating radiation detection equipment (historically).

- Research into nuclear decay, atomic structure, and radiochemistry.

Today, radium’s direct industrial and medical uses are limited because of safety and supply issues; however, it retains importance as a historical cornerstone of nuclear science and as a reference point for understanding radioisotopes and decay chains.

Health, Safety, and Environmental Impact

Exposure to radium presents serious health risks because its decay emits high-energy particles and it can bioaccumulate in bone tissue due to chemical similarity with calcium. When radium is taken into the body, alpha radiation can damage bone marrow and surrounding tissues, increasing the risk of bone cancers and other disorders.

Pathways of exposure

- Ingestion of contaminated water containing radium dissolved from bedrock.

- Inhalation of radon gas produced by radium decay, especially in poorly ventilated buildings.

- Occupational exposure in mining and processing of uranium-bearing ores or handling legacy radium sources.

Modern radiation protection principles—time, distance, and shielding—apply rigorously wherever radium is present. Regulatory frameworks control radium-bearing waste, radon mitigation in buildings, and the handling and disposal of legacy sources. Medical use of radioactive materials is tightly controlled to minimize doses to patients and staff.

Cultural and Historical Legacy

Radium entered public imagination not only as a scientific breakthrough but also as a symbol of modernity and danger. The stories of early researchers who experienced radiation sickness and of workers who suffered from chronic exposures helped drive the development of occupational health standards and the modern field of radiological protection.

Iconic figures and stories

- Marie Curie‘s tireless research and the enormous personal cost she paid in terms of health.

- The “radium girls” whose illnesses and legal cases in the early 20th century catalyzed safer workplace practices.

- Public fascination with glow-in-the-dark products and the eventual backlash that led to stricter regulation.

Radium also fueled artistic and literary imagery—its invisible power and eerie glow serving as metaphors for unseen forces and the double-edged nature of scientific progress.

Modern Research and Future Prospects

Although radium itself is no longer a frontline industrial or medical material, research related to radium and its decay products continues to be relevant. Studies focus on:

- Radium isotopes as tracers in geochemical and hydrological research to understand groundwater movement and sediment formation.

- Environmental remediation techniques for radium-contaminated sites, including removal and stabilization of radioactive scales and sediments.

- Radiation biology research: studying the biological effects of alpha-emitting isotopes informs safer handling of other alpha-emitting therapeutic isotopes now used in targeted cancer treatments (for example, actinium-225 and radium-223 in specific protocols).

In a notable modern medical application, Ra-223 (radium-223 dichloride) has been developed as a targeted therapeutic agent for specific bone metastases in cancer patients, demonstrating that with strict control and proper formulation, alpha-emitting isotopes can play a valuable role in medicine. This revival of radium-based therapy in a highly regulated and targeted form underscores the continuing scientific interest in harnessing radioisotopes safely and effectively.

Interesting Facts and Lesser-Known Aspects

Several details about radium are particularly fascinating:

- The discovery of radium contributed directly to the understanding that atoms were not indivisible and led to the acceptance that elements could transform into other elements—an idea that reshaped chemistry and physics.

- Radium’s bright aura in early experiments was often enhanced by mixing radium salts with phosphors; pure radium salts are not self-luminescent in darkness without a phosphor.

- Environmental radium concentrations vary widely depending on regional geology; building codes and public health policies in many areas now consider local radon potential as a routine part of construction and remediation planning.

- Historically, the scarcity and cost of radium made it more valuable than gold at times during the early 20th century.

The complex mixture of utility, danger, and scientific importance makes radium an enduringly compelling topic. It serves as both a cautionary tale about unintended consequences and as an inspiration for how careful science and regulation can convert hazardous phenomena into precise and beneficial tools.

Further Reading and Resources

For readers interested in exploring radium more deeply, worthwhile directions include historical biographies of early radiochemists, modern textbooks on nuclear chemistry and radiological protection, and guidelines from national health and environmental agencies on radon and radium safety. Institutions that maintain historical collections of early radiochemical equipment often provide valuable context on how dramatic the early experiments were and how they shaped modern science.