The opal has fascinated people for centuries with its shimmering surface and seemingly magical flashes of color. This article explores the stone from many angles: what it is, how and where it forms, the major sources and mining regions, its practical and artistic applications, and the scientific and cultural stories that surround it. Along the way you will find practical guidance for collectors, insights into market and treatment issues, and a closer look at why opal remains one of the most compelling subjects in modern gemology. The following sections will take you deeper into the geology, the variants beloved by jewelers, and the human narratives woven around this extraordinary gemstone.

What is Opal? Composition, Structure and Optical Phenomena

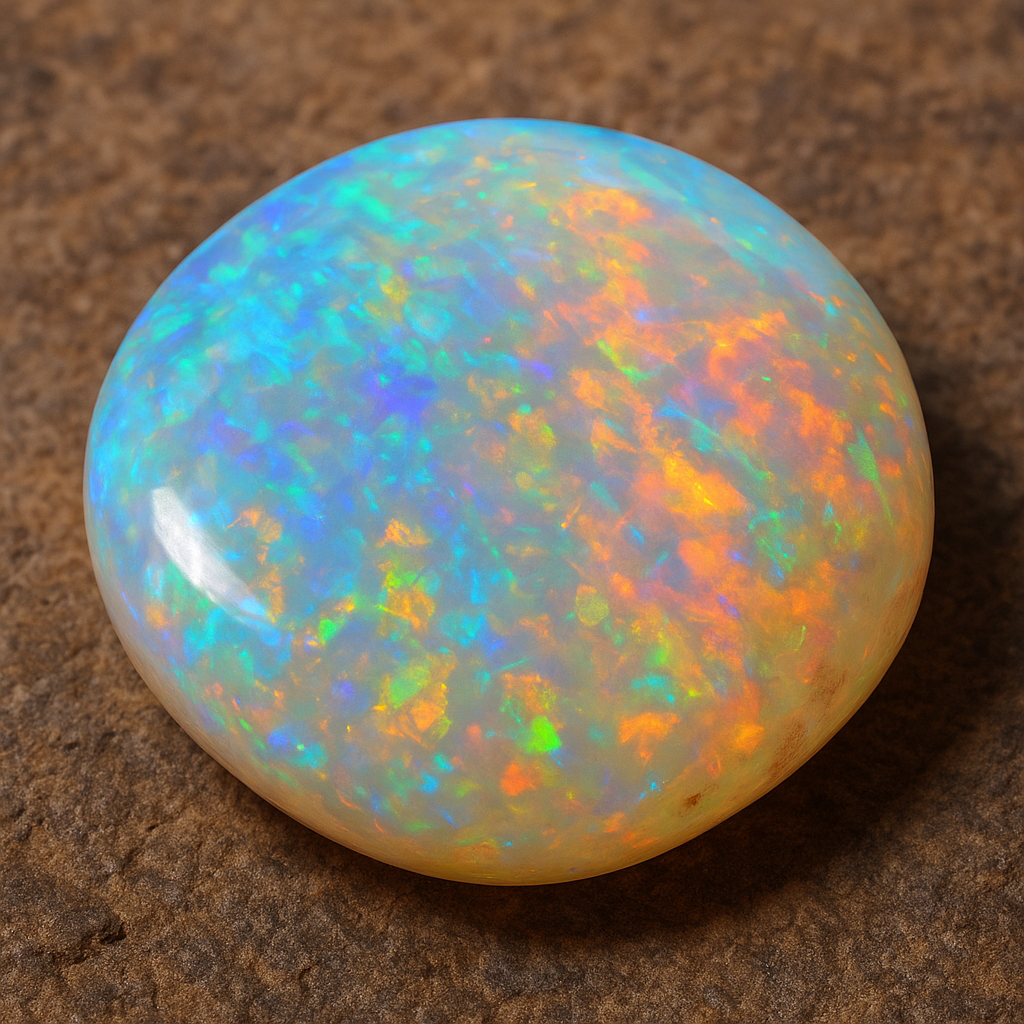

At its core, opal is a form of amorphous silica—essentially hydrated silica—that contains water molecules trapped within a glass-like silica matrix. Unlike crystalline gemstones such as quartz or diamond, opal lacks long-range atomic order. Its internal arrangement of tiny silica spheres can diffract light, producing a phenomenon known as play-of-color. That play-of-color is what most people think of when they imagine an opal: flashes of red, green, blue and every hue in between shifting across the stone as it moves.

How the play-of-color works

When silica spheres within an opal are uniform in size and closely packed in a regular array, they form microscopic structures that act like a three-dimensional diffraction grating. Incident light is split and recombined, with different wavelengths being constructively interfered at different viewing angles. The specific colors produced depend on the sphere size and spacing: larger spheres tend to diffract longer wavelengths (reds and oranges), while smaller spheres favor shorter wavelengths (blues and violets).

Varieties and classifications

Opal comes in a surprising number of forms, each prized for different reasons. Common classification categories include:

- Precious opal — displays play-of-color and is prized as a gem.

- Common opal (potch) — lacks the play-of-color and is often used for carvings or as a collector’s specimen.

- Fire opal — typically orange to red or yellow, often transparent to translucent; Mexican fire opal is a famous example.

- Black opal — has a dark body tone that enhances the play-of-color; the most famous and valuable black opals come from Australia.

- White opal — lighter body tone with pastel play-of-color.

- Matrix opal — opal occurring within or mixed with the host rock, often creating dramatic patterns.

- Opalized fossils — organic material replaced by opal, sometimes preserving fine biological detail.

These varieties reflect differences in formation environment, silica concentration, impurities, and the presence of trace elements that can affect color and transparency.

Where Opal Occurs: Major Localities and Geological Settings

Opal formation is closely linked to the movement and deposition of silica-rich solutions in favorable geological settings. It commonly forms in sedimentary basins, within cavities, fractures, and the porous spaces of volcanic ash and weathered materials. Groundwater transporting dissolved silica can precipitate opal when conditions change—pressure, temperature, pH or evaporation rates. The most productive and famous sources are concentrated, but opal is found on several continents.

Australia — the dominant source

Australia has dominated the opal market for more than a century, producing over 90% of the world’s gem-quality opal. Notable Australian fields include Lightning Ridge (black opal), Coober Pedy (white and crystal opal), Andamooka, and Mintabie. Australian opals are typically found in sedimentary rocks—silica-rich solutions infiltrated fissures and voids in ancient sandstones and mudstones, producing spectacular deposits.

Other important localities

- Ethiopia — since the late 2000s, Ethiopian opal (often from the Wollo region) has become prominent. These opals can be hydrophane (absorbing water) and exhibit vivid play-of-color.

- Mexico — famous for transparent to translucent fire opal, often vividly orange or red. Mexican opal nodules are frequently found in volcanic tuff and basaltic environments.

- United States — Nevada and Idaho produce precious opal, including black and crystal forms. Virgin Valley, Nevada is known for high-quality black opal.

- Brazil, Honduras, Indonesia, Slovakia — all produce opal in smaller quantities, with local varieties sometimes unique in appearance or occurrence.

Geologically, opals are most commonly associated with silica-rich sediments, volcanic ash layers, and hydrothermal activity. The interplay of climate (evaporation), groundwater chemistry, and host rock porosity determines whether opal will form and what variety evolves.

Uses and Applications: Jewelry, Industry, and Cultural Roles

Opal’s primary modern use is in jewelry, where its dynamic color has been exploited in rings, pendants, earrings, brooches, and inlays. But opal’s value extends beyond adornment: it has roles in cultural artefacts, scientific research, and even inspiring technological innovation.

Jewelry and decorative art

- Precious opal is routinely faceted or cabochon-cut; cabochons are most common because the play-of-color is best displayed on smooth domes.

- Doublets and triplets—composite stones made by gluing thin slices of opal to backing (doublet) and adding a protective cap (triplet)—make thin opal layers wearable and more affordable.

- Carved opal is used for cameos, beads, and ornamental objects, especially when patterns or matrix structures create intriguing surfaces.

Scientific and technological inspirations

Although natural opal is not used directly as an industrial material in the same way as quartz, the ordered sphere structures within opal have inspired research into photonic crystals—engineered materials that control light for sensors, optical components, and telecommunications. Synthetic opal-like materials, modeled after natural opal’s diffraction mechanisms, help researchers explore light-management strategies for solar cells and display technologies.

Cultural, historical and healing traditions

Across cultures, opal has carried numerous symbolic meanings: creativity, protection, and emotional amplification among them. Historical attitudes have sometimes veered into superstition—for example, a 19th-century European belief that opals brought bad luck—yet many societies have treasured opals as lucky and protective talismans. In contemporary holistic circles, opal is often associated with emotional healing and enhanced perception, although such claims are metaphysical rather than scientific.

Mining, Treatments, Synthetics and Market Considerations

Understanding how opals enter the marketplace is critical for buyers and collectors. The journey from mine to market can include cutting, stabilization, treatments, and the introduction of laboratory-grown stones. Each step affects value, durability, and appearance.

Mining and extraction methods

Opal mining ranges from artisanal hand-dug operations to mechanized open-cut and underground mines. Methods include:

- Shallow pit mining with hand tools and small-scale equipment.

- Underground tunneling to follow opal-bearing seams.

- Large-scale surface mining where overburden is removed and stratified layers are processed.

Because opal nodules can be irregular and fragile, careful extraction is essential to preserve gem-quality material.

Treatments, stabilizations and imitations

Several treatments are used to enhance or stabilize opal, and collectors should be aware of them:

- Sugar and acid treatment — often used on low-grade Ethiopian opal to darken the background tone and accentuate play-of-color.

- Smoke treatment — exposing opal to smoke to deepen body tone and increase apparent contrast.

- Impregnation or stabilization — using resins or oils to fill cracks and reduce porosity; common with fragile specimens but may affect long-term value.

- Doublets and triplets — economical ways to display thin opal slices; they are legitimate products but differ in value from solid opals.

Synthetic opals, produced since the mid-20th century, mimic the ordered silica-sphere structures responsible for play-of-color. Well-known methods include the Gilson process, which creates convincing opal simulants. Advances in lab-grown materials mean that spectroscopy, magnification, and expert gemological testing may be necessary to distinguish natural opal from high-quality synthetics.

Valuation factors

Opal pricing depends on several interrelated criteria:

- Color and intensity of the play-of-color — brightness and range of hues strongly influence price.

- Pattern — rare and distinct patterns (harlequin, pinfire, rolling flash) attract premiums.

- Body tone — from black (most valuable for contrast) to white and crystal.

- Clarity and transparency — crystal opals with transparent bodies can be highly prized.

- Cut and size — well-cut cabochons that maximize color are more valuable; large stones with excellent play-of-color command high prices.

- Origin — provenance, especially from famed fields such as Lightning Ridge, can increase desirability.

Identification and Care: Keeping Opal Beautiful and Stable

Because opal is relatively soft (about 5.5–6.5 on the Mohs scale) and contains water within its structure, it requires special handling. Storage, cleaning, and wear practices can prolong its life and preserve color.

Basic care rules

- Avoid sudden temperature or humidity changes — opal can craze (develop hairline cracks) if it dries too quickly or is heated abruptly.

- Store opal separately from harder gemstones to prevent abrasion; soft cloth pouches or padded compartments are ideal.

- Cleaning — use mild soap and water with a soft cloth or brush; avoid ultrasonic cleaners, steam, and harsh chemicals, especially for stabilized or treated opals.

- Restringing and mounting — lab-grown resins and glues can degrade; professional inspection is recommended for antique or treated pieces.

Identification tips

Basic tests and observations can help distinguish natural opal from imitations and synthetics:

- Magnification — synthetic opals often show a regular columnar or lizard-skin pattern under high magnification, while natural opal shows irregular play-of-color distribution.

- Back and side views — doublets and triplets may reveal layered construction; a dark backing is common on doublets to enhance contrast.

- Hydrophane behavior — some Ethiopian opals absorb water and temporarily lose play-of-color or change translucency; this property can help identify origin but also signals care needs.

- Laboratory testing — advanced spectroscopy, luminescence, and density tests are available from gemological labs to confirm origin and treatment.

Cultural History and Famous Opals

Opals have played prominent roles in human culture from antiquity to the present. Roman writers praised their beauty; medieval Europeans assigned mystical properties; modern collectors treasure certain historical stones. A few celebrated opals include:

- The Andamooka Opal — presented to Queen Elizabeth II, noted for its size and intense color.

- The Olympic Australis — once considered the largest and finest gem-quality opal, unearthed in South Australia.

- Various museum specimens — opalized fossils and spectacular black opals displayed in national collections.

These famous stones helped cement the opal’s reputation and highlighted regional mining booms that shaped local economies and culture, particularly in Australian outback towns where opal mining became a way of life.

Collecting and Lapidary Practices

For collectors and hobby lapidaries, opal presents both opportunity and challenge. Solid opal gemstones can be extremely valuable, while attractive specimens for cutting are often irregular and fragile. Good practices include:

- Buying from reputable dealers who disclose treatments, origin, and whether a stone is a doublet or triplet.

- Learning to recognize common patterns and body tones to make informed purchases.

- Using gentle cutting and polishing techniques — cabochon shaping is typical; water-cooled diamond tools and cautious polishing with cerium or tin oxide are recommended.

- Considering composite options — doublets and triplets can showcase rare patterns at lower cost but require awareness of care differences and longevity concerns.

Collectors often cherish opals both for their beauty and for the geological stories they tell. Opalized wood, bones and shells preserve ancient life and climate indicators, making them scientifically valuable as well as visually striking.

Conclusion

Opal occupies a unique place among gemstones: simultaneously fragile and resilient in the human imagination, scientifically intriguing and artistically inspiring. From the dusty opal fields of Australia to the volcanic tuffs of Mexico and the newfound deposits of Ethiopia, opal continues to surprise with new material and new applications. Whether approached as a collector, jeweler, scientist, or simply an admirer of natural beauty, the opal rewards close attention: its internal architecture, the dance of color, and its cultural narratives together create a multifaceted subject worth exploring for years to come.