Marcasite is a fascinating mineral that often surprises people who encounter it for the first time. Composed of iron and sulfur, it shares chemical similarities with pyrite but differs in crystal form and behavior. This article explores where marcasite forms, how it behaves physically and chemically, its historical and modern uses, and several intriguing aspects that make it a subject of interest for collectors, geologists, and conservators. Along the way you will encounter discussions of formation environments, identification tips, conservation challenges, and cultural connections to this often misunderstood mineral.

Occurrence and Geological Formation

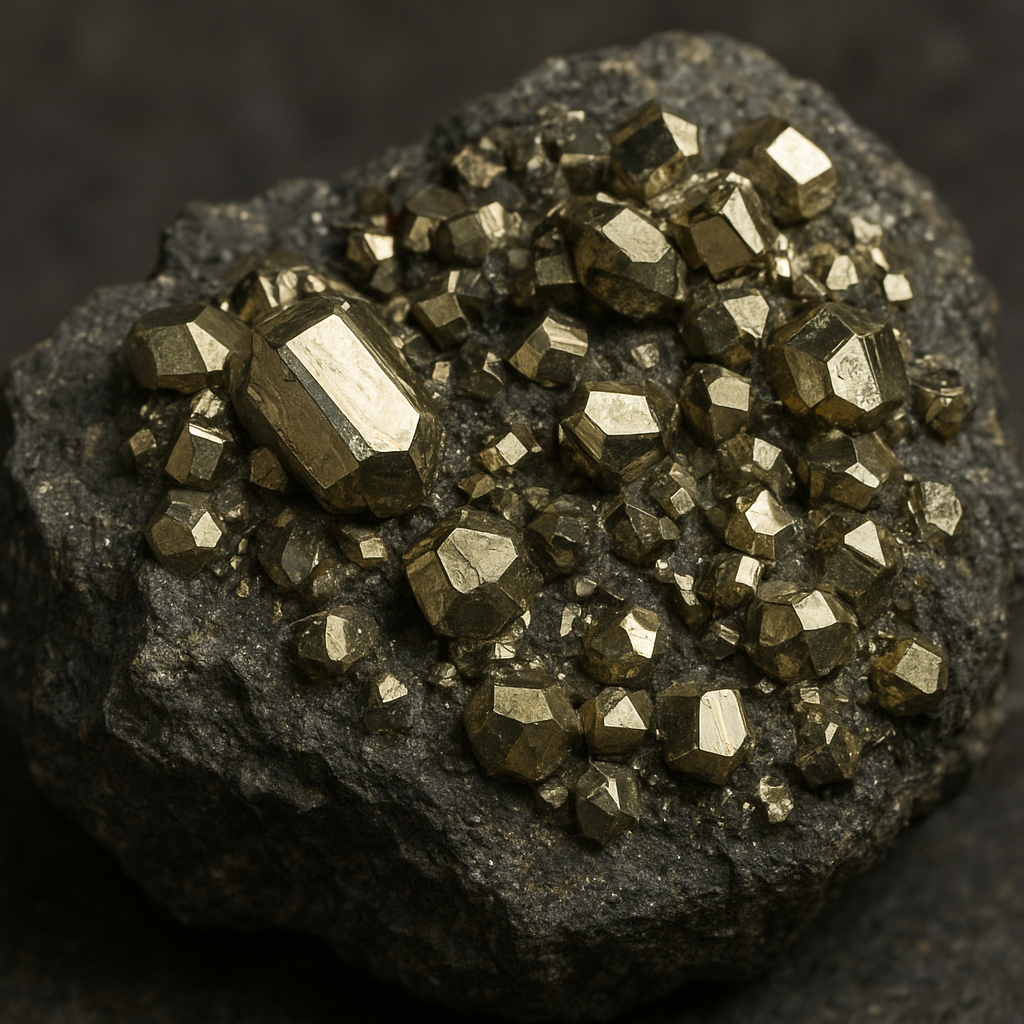

Marcasite is an iron sulfide mineral with the chemical formula FeS2. In many respects it is a close relative of pyrite, but the two are distinct minerals with different crystal systems and stability ranges. Marcasite typically forms in low-temperature environments, and is commonly associated with sedimentary rocks, especially those rich in organic matter, as well as in veins formed at relatively low temperatures. It is widespread and can be found on every continent where suitable geological conditions have existed.

Common geological settings for marcasite formation include:

- Diagenetic layers within shale, mudstone, and other fine-grained marine sediments, where bacterial sulfate reduction produces sulfide that reacts with iron.

- Low-temperature hydrothermal veins and replacement zones, often along faults or fractures where mineralizing fluids circulate near the surface.

- Coal seams and carbon-rich layers, where reducing conditions favor iron sulfide precipitation during early diagenesis.

- Evaporitic and carbonate settings where changes in pH and redox conditions locally favor marcasite formation over pyrite.

Marcasite often forms when conditions are slightly more acidic or when iron and sulfide become available more rapidly than in environments that favor pyrite. Because marcasite is less stable than pyrite at moderate temperatures and over geological timescales, it is frequently found as a metastable phase that either transforms into pyrite or oxidizes into secondary minerals, depending on environmental conditions. Framboidal and nodular aggregates—collections of tiny spherical crystals—are characteristic textural features seen in many sedimentary occurrences and may record rapid nucleation events during early diagenesis.

Crystal Structure, Appearance, and Properties

At the heart of the distinction between marcasite and its more famous cousin is crystal structure. Marcasite crystallizes in an orthorhombic system, producing tabular, spear-shaped, or bladed crystals that often twinned and can aggregate into complex groups. These habits contrast sharply with the cubic crystals and pyritohedral forms of pyrite. The crystallography of marcasite has made it a subject of study for mineralogists interested in polymorphism and phase stability among sulfide minerals.

Key physical properties of marcasite include a metallic luster and a pale brass-yellow color that can tarnish to shades of gray, brown, or iridescent hues. Its hardness typically ranges around 6 to 6.5 on the Mohs scale, and it has a specific gravity generally near 4.8 to 4.9—similar but not identical to pyrite. Marcasite’s streak is usually dark gray to black, and it is brittle with a tendency to fracture rather than cleave cleanly. Microscopic textures may reveal framboidal structures—tiny raspberry-like clusters of microcrystals—that are particularly common in sediment-hosted occurrences.

One of marcasite’s most consequential properties is its chemical instability in the presence of heat, humidity, and oxygen. Over time, marcasite can oxidize to produce iron oxides, hydroxides, and sulfate salts; this alteration is a central concern for conservators and collectors because it can cause specimens and jewelry to crumble or develop damaging efflorescences.

Typical Mineral Associations and Field Identification

Marcasite commonly occurs alongside a suite of sulfide and gangue minerals. Typical associates include sphalerite, galena, chalcopyrite, pyrite, and various carbonate minerals. In sedimentary rocks it may be intimately mixed with organic matter, and in some ore deposits marcasite can be a minor component of the ore even when pyrite dominates.

Field identification of marcasite relies on a combination of crystal habit and contextual clues. Useful indicators include:

- Crystal shape: spear-shaped, bladed, or tabular crystals rather than the cubes typical of pyrite.

- Color and tarnish: a paler yellow-brass tone that tarnishes more quickly and unevenly than pyrite.

- Brittleness: a tendency to flake or powder under stress, sometimes leading to a crumbly surface.

- Streak: a dark gray to black streak, often similar to pyrite but combined with other traits it can support identification.

Because marcasite can alter to other minerals, its original form is not always obvious in weathered outcrops. Careful microscopic examination and, when necessary, X-ray diffraction are used to confirm identification in ambiguous cases.

Uses, Historical Significance and Decorative Applications

Marcasite has had a range of uses through history, though it has never been as economically important as some other sulfide minerals. Historically, iron sulfides including marcasite were sometimes used as cheap sources of sulfur and as minor iron ores in local contexts. More visible culturally has been the use of marcasite and pyrite in ornamental contexts.

The term “marcasite” is often attached to antique and vintage jewelry. In many cases the small faceted metallic stones set in silver in Victorian and Art Deco pieces are actually pyrite, but they are generically called marcasite in the jewelry trade. Their bright metallic sparkle, when set against dark silver, created a popular look in the 18th and 19th centuries. Actual marcasite was also used, though its chemical instability made it a problematic choice; oxidizing marcasite in jewelry can cause damage to the stone and the metal setting over time. For this reason, careful fans of jewelry preservation are vigilant about storage and environmental control for pieces containing true marcasite.

Beyond ornamentation, marcasite is valued by geoscientists and petroleum geologists because it can record conditions of formation in sediments, including redox conditions, rates of sedimentation, and microbial activity. In some petroleum-bearing basins, the presence of marcasite versus pyrite is used as a proxy for depositional environment and can inform exploration strategies. Collectors prize well-formed marcasite crystals and rosettes, and polished sections are used in educational contexts to illustrate mineral textures and early diagenetic processes.

Deterioration, Conservation Challenges and Care

One of the most notorious aspects of marcasite is its tendency to self-destruct under unfavorable conditions. This process—informally known among conservators as marcasite disease—occurs when marcasite oxidizes in the presence of moisture and oxygen to produce acidic iron sulfate solutions. These products can etch and powder the original mineral and can corrode adjacent materials such as silver settings or display mounts.

Conservation recommendations for both specimens and jewelry containing marcasite include:

- Controlled low-humidity storage (ideally below 40% relative humidity) with desiccants such as silica gel.

- Avoidance of aqueous cleaning methods or exposure to oils that can trap moisture.

- Stable, non-acidic packing materials and avoidance of materials that release volatile acids or sulfides.

- Regular inspection to detect early signs of efflorescence or powdering, and consultation with conservation professionals for treatment of valuable pieces or museum specimens.

For jewelry, preventive measures include wearing only infrequently, keeping pieces dry, and storing them separately from humid environments. Because the oxidation products can be acidic, prompt action is advised when deterioration is first detected to minimize collateral damage.

Scientific Interest and Research Topics

Marcasite is not only a collector’s curiosity; it is a subject of active scientific research. Topics of interest include:

- Understanding why marcasite forms instead of pyrite under particular chemical and biological conditions, which informs models of early diagenesis.

- Investigations into microbial mediation of iron and sulfur cycles, since sulfate-reducing bacteria can influence the nature of sulfide minerals precipitated in sediments.

- Studies of oxidation pathways and the environmental consequences of sulfide mineral weathering, particularly the formation of acid sulfate soils and impacts on metal mobility.

- Crystallographic studies that probe the metastability of marcasite and its transformation kinetics toward pyrite or secondary oxidation products.

These scientific pursuits are important not only to mineralogists but also to environmental scientists, petroleum geologists, and astrobiologists. The latter are interested in sulfide minerals like marcasite because sulfide deposits can preserve biosignatures and record conditions favorable to microbial life on Earth and potentially on other planets.

How to Distinguish Marcasite from Pyrite and Careful Collecting

For collectors and enthusiasts, distinguishing marcasite from pyrite is both practical and necessary for proper care. Key tips include:

- Examine crystal habit closely: look for bladed or spear-shaped forms and characteristic twinning indicative of marcasite.

- Note the fragility of the specimen: marcasite-bearing pieces that flake or powder easily should be treated with high caution.

- Ask about provenance: specimens from low-temperature sedimentary deposits are more likely to contain marcasite, while high-temperature hydrothermal veins more commonly yield stable pyrite.

- When in doubt, seek professional identification such as X-ray diffraction or expert microscopic analysis.

Conscientious collecting also involves considering conservation from the outset: storing specimens in controlled humidity, documenting any changes, and choosing display conditions that minimize light, heat, and moisture exposure. These practices preserve both the scientific value and aesthetic appeal of marcasite samples.

Interesting Cultural and Practical Notes

Marcasite has woven its way into craft, jewelry, and scientific narratives. Some interesting points worth noting:

- In decorative arts, the term “marcasite” is often used loosely to denote fashionable metallic stones in silver settings; authenticity varies and many “marcasite” jewels are actually pyrite.

- Because marcasite oxidation can produce sulfuric acid, historical artifacts containing marcasite that have degraded may pose conservation challenges in museums, requiring specialized treatment.

- As a recorder of environmental conditions in sediments, marcasite helps reconstruct ancient depositional settings and can even preserve microscopic fossils or organic remains within its matrix.

- Modern research sometimes leverages marcasite and related sulfides as model systems for studying solid-state transformations, corrosion, and the interplay between mineralogy and microbiology.

Whether encountered as a shimmering display specimen, a vintage brooch, or a blackened clod in a mudstone, marcasite opens a window onto the chemistry of the near-surface Earth and the delicate interplay between minerals, microbes, and the atmosphere.