Magnesite is a mineral with a deceptively simple chemical formula yet a complex and varied role across geology, industry and emerging technologies. Formed in several geological settings and valued primarily as a source of magnesium and magnesium oxide, this carbonate mineral has been used for centuries and is now central to high-temperature industries, environmental applications and experimental energy storage technologies. The following article explores what magnesite is, where it occurs, how it is processed and used, and several intriguing aspects of its chemistry and global importance.

What magnesite is: composition and physical properties

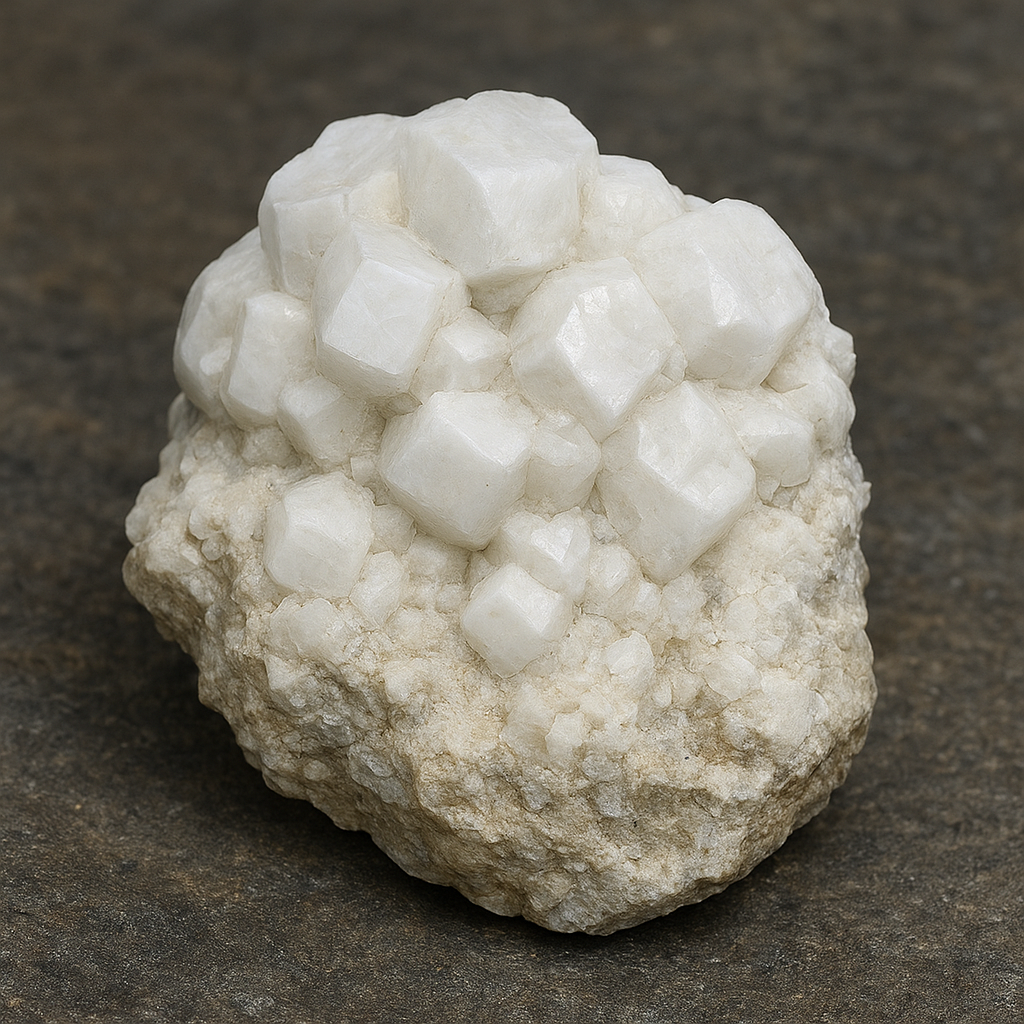

Magnesite is the mineral form of magnesium carbonate, with the chemical formula MgCO3. It commonly occurs as white to gray masses or crystals, and may be granular, fibrous, or compact. In hand specimen it is often mistaken for other light-colored carbonates such as calcite or dolomite, but it can be distinguished by its reaction with acids (slow effervescence in cold dilute hydrochloric acid unless powdered), hardness (Mohs ~3.5–4.5), and specific gravity (~3.0). Magnetism is absent, and its fracture is uneven to subconchoidal.

The most industrially important chemical derived from magnesite is magnesia, broadly called MgO, produced by calcination (heating) of the mineral. Different calcination temperatures give products with varying properties: low-temperature calcination yields light-burned magnesia that is reactive and used in chemical industries and agriculture, while high-temperature calcination produces dead-burned magnesia with low reactivity and excellent thermal stability, critical for refractory linings.

Global occurrence and geological settings

Magnesite forms in several distinct environments, each giving characteristic textures and deposit geometries:

- Hydrothermal veins: Hot, Mg-rich fluids circulating through rock fractures can precipitate magnesite as vein fills. These are common in orogenic belts where metamorphism releases magnesium from mafic rocks.

- Metamorphic and serpentinite-related deposits: Serpentinization of ultramafic rocks and later carbonation (introduction of CO2-bearing fluids) can convert serpentine and olivine into magnesite, often forming large replacement bodies or listvenite. These are among the most important magnesite sources globally.

- Sedimentary replacements: Marine or lacustrine carbonate sediments rich in magnesium, or diagenetic processes replacing limestone, can form stratiform magnesite beds.

- Residual deposits: Weathering and leaching of magnesium-rich rocks can leave concentration of magnesite in soils or residual placers.

Major producing regions

Significant magnesite deposits are found worldwide. Key producers include:

- China — the largest global producer, with vast reserves used for refractory and chemical industries.

- Turkey and Greece — long histories of magnesite mining, producing both ornamental stone and industrial feedstock.

- Austria, Russia, Brazil, Australia, and the United States — important regional producers with varied deposit types.

Geological exploration often targets ultramafic terrains, contact zones between mafic/ultramafic units and carbonates, and regions with known hydrothermal activity.

Mining, beneficiation and processing

Extraction methods vary by deposit type: open-pit and underground mining are both used. After extraction, magnesite is beneficiated to remove impurities such as silica, iron oxides and clay. Typical processing steps include crushing, grinding, magnetic separation (to remove iron), flotation and sometimes chemical leaching for specific applications.

Calcination and products

Calcination is the key transformation: MgCO3 → MgO + CO2. Temperature and atmosphere control determine the product:

- Light-burned magnesia (calcined at 700–1000 °C) — more reactive, used for agricultural lime, chemical feedstocks and basic refractory cements.

- Caustic or dead-burned magnesia (calcined above 1500 °C) — low reactivity, high-density product used for high-temperature refractory bricks and linings in furnaces, kilns and steelmaking equipment.

- Magnesium hydroxide (Mg(OH)2) and hydromagnesite can be produced by slaking or precipitation routes and are used as flame retardants and fillers.

Further chemical processing can yield magnesium chloride, magnesium sulfate, and metallic magnesium through reduction or electrolytic routes, linking magnesite to broader magnesium metallurgy.

Industrial applications

Magnesite’s primary industrial role is as a source of magnesia for high-temperature (refractory) applications. But its uses are diverse:

Refractories and metallurgy

- Dead-burned magnesia is the cornerstone of refractories for steelmaking converters, electric arc furnaces, and glass furnaces due to its high melting point and resistance to basic slags.

- Magnesia-carbon bricks combine magnesia with carbon to resist chemical attack and thermal shock in demanding metallurgical settings.

Chemical industry and agriculture

- MgO and derivatives are used as catalysts, pH regulators and raw materials for producing magnesium salts.

- In agriculture, powdered magnesite-derived products serve as magnesium fertilizers and soil amendments where magnesium deficiency is a crop issue.

Construction materials

- Magnesium oxychloride and oxysulfate cements, produced from magnesia, have fast-setting properties and are used in floorings, binders and specialty construction applications.

- Light-burned magnesia is an ingredient in some specialty cements and boards with fire-resistant properties.

Environmental and niche uses

- Magnesia-based products serve as neutralizers for acidic waste streams and flue gas desulfurization in power plants.

- Carbon capture: natural and engineered carbonation reactions involving magnesium-bearing minerals (including magnesite formation) are studied for permanent CO2 sequestration because magnesium carbonates can lock CO2 into stable mineral phases.

- Magnesium hydroxide and hydromagnesite are used as flame retardants and smoke suppressants in polymer formulations.

Other applications and emerging research

Research keeps expanding magnesite-related opportunities. A few areas of interest:

Energy storage and batteries

Magnesium metal and magnesium-ion batteries are subjects of intense research. While magnesite itself is not directly the battery electrode, it is a potential precursor for magnesium compounds and metal via thermal or chemical processing. Researchers also explore magnesium oxide and hydroxide as protective layers, solid electrolytes or precursor materials in next-generation battery chemistries.

CO2 mineralization and environmental remediation

Because the carbonate form is thermodynamically stable, converting CO2 into solid magnesium carbonates offers a route to permanent sequestration. Natural processes that form magnesite over geological timescales are slow, but engineered approaches — using brines, ultramafic rocks, or accelerated carbonation of magnesium-rich wastes — aim to speed this up. Some wastewater treatment processes also use Mg-bearing materials to precipitate contaminants.

Architectural and decorative stone

Some dense, attractive magnesite varieties are cut as ornamental stone or used where a durable, slightly reactive carbonate surface is acceptable. Historical artifacts and tiles sometimes use magnesite compositions, and its distinctive textures can be valued in design contexts.

Interesting mineralogical and historical notes

Magnesite carries a variety of intriguing facts that bridge geology, history and technology:

- The name derives from the Magnesia region of ancient Greece, where magnesium-rich minerals were first described.

- Fossil pseudomorphs: magnesite can replace earlier carbonates, preserving textures that tell stories about fluid evolution and diagenesis in the rock record.

- Thermal decomposition of magnesite releases CO2, making the calcination step in magnesia production a focus for emissions management and process innovation.

Environmental, economic and social considerations

Like many industrial minerals, magnesite mining and processing have environmental footprints. Key considerations include:

- CO2 emissions from calcination — because MgCO3 releases CO2 when converted to MgO, magnesia production contributes to greenhouse gas emissions unless CO2 is captured or offset.

- Land disturbance and habitat impacts from mining operations; responsible rehabilitation is critical, especially in karst or sensitive ultramafic terrains.

- Water use and effluent management in beneficiation and chemical conversion processes.

Economically, magnesite is strategically important for steelmaking and refractory industries. Supply concentration (e.g., high production in China) can create market sensitivities. Investment in beneficiation, quality control and alternative feedstocks (like synthetic magnesia from brines) affects regional competitiveness.

Processing challenges and technological innovations

Optimizing magnesite processing faces several technical challenges. Removing silica and iron contaminants is essential for high-purity MgO. Controlling calcination to obtain desired reactivity without excessive energy consumption requires precise kiln management. Innovations include fluidized-bed calcination for better temperature control, use of mechanical activation to enhance reactivity at lower temperatures, and integration of carbon capture technologies with magnesia plants.

Another avenue is valorizing lower-grade deposits by producing value-added products such as precipitated magnesium carbonate, magnesium hydroxide flame retardants, or specialty cements, thereby reducing waste and improving economics.

Practical tips for collectors and students

For mineral collectors, magnesite is an accessible and instructive specimen. When identifying magnesite:

- Test hardness and simple streak; note that it is softer than quartz but harder than talc.

- Perform acid tests carefully — coarse samples may react slowly; powdering increases reaction speed.

- Observe associations — magnesite often appears with serpentine, talc, dolomite and other Mg-rich minerals, which helps in field identification.

In laboratory settings, synthetic magnesite analogues and controlled carbonation experiments are used to study mineral formation kinetics, CO2 uptake capacities and potential sequestration pathways.

Final observations on magnesite’s role

Magnesite stands at the intersection of traditional industry and forward-looking science. As the primary natural source of magnesia, it supports steel, glass and refractory sectors. At the same time, its chemistry is pivotal in environmental strategies like carbon capture and in research into magnesium-based energy technologies. Balancing the environmental footprint of production with the material’s unique properties will guide future developments in mining, processing and end-use innovation.

magnesite magnesium magnesium carbonate magnesia ore refractory thermal stability cement carbon capture battery hydromagnesite