Iris agate is a captivating variety of banded quartz prized for its subtle rainbow sheen and delicate internal structures. Collectors, jewelers and geologists alike are drawn to its mixture of familiarity and rarity: although it belongs to the broad family of common agates, certain specimens display a striking play of color when sliced thin or polished just right. This article explores the origins, physical properties, geographical occurrences, practical uses, and cultural associations of this fascinating material, as well as practical guidance for identification, cutting and care.

What Iris Agate Is and How It Forms

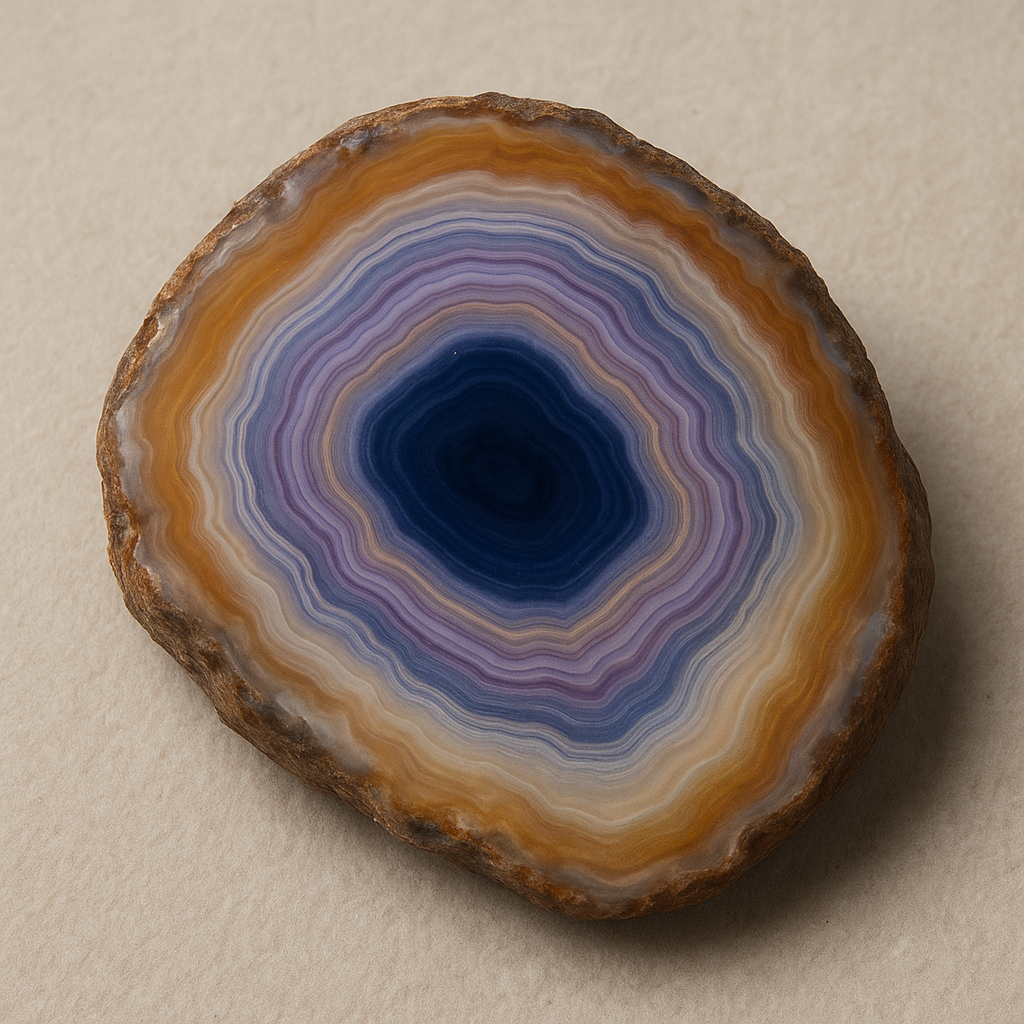

At its core, iris agate is a form of agate, itself a banded variety of chalcedony, which is a microcrystalline form of silica. The characteristic bands of agate arise when silica-rich fluids repeatedly fill cavities in volcanic or, occasionally, sedimentary rocks. Over time, layers of microcrystalline quartz are deposited with subtle shifts in composition, impurities and crystal orientation, producing the concentric or layered patterns that define agate.

The feature that distinguishes iris agate from many other agates is an optical phenomenon akin to a faint rainbow or sheen known as iridescence. This effect is not due to a single cause universally; instead, it can result from a few geological microstructures and processes:

- Very thin, semi-translucent layers — when slices are polished thin, light interference between fine layers can produce spectral colors.

- Microscopic inclusions — minute inclusions of other minerals or fluid inclusions arranged in a way that diffracts light.

- Polishing and orientation effects — the orientation of banding relative to the cut, and the quality of the polish, accentuate the effect.

- Stress fractures and coatings — natural microfractures healed by silica or mineral films may act as thin films and generate interference colors.

Because the mechanism often involves delicate structural features at the scale of micrometers, iris effects are best revealed by careful lapidary work and backlighting, and can disappear if a specimen is ground away too aggressively.

Where Iris Agate Occurs

Iris agate is not a formally classified mineral species but a descriptive trade term applied to agates showing specific optical qualities. Accordingly, it can be found in several classic agate-producing regions worldwide. The most notable occurrences include:

- Brazil — one of the premier sources of agate and geode material; certain Brazilian agates exhibit iridescent layers when sliced thin.

- Mexico — regions like Chihuahua produce colorful and banded agates, some showing iridescent sheens under the right cutting conditions.

- Madagascar — known for a broad variety of agates and jaspers, Madagascar also yields translucent slices that may display an iris effect.

- India — the Deccan Traps and nearby areas have long-supplied agates; thin slices from select localities sometimes reveal subtle color play.

- United States — various states (Oregon, Montana, Arizona) produce banded agates; occasional specimens have been marketed as iris or rainbow-enhanced agates.

- Uruguay and other South American localities — known for high-quality chalcedony and agates with striking internal patterns.

One important point for collectors: the iris effect is more a property of particular nodules or seams than of entire localities. Within a single deposit, some nodules may show exceptional coloration while adjacent ones remain ordinary.

Physical Properties and Identification

Because iris agate is fundamentally a variety of chalcedony, its broad physical properties match those of microcrystalline quartz:

- Hardness around 6.5–7 on the Mohs scale, making it fairly durable for jewelry.

- Conchoidal to uneven fracture; not cleavable.

- Translucent to opaque; iris specimens are often more translucent when thinly sliced.

- Specific gravity roughly 2.6–2.7.

Identification of a true iris effect versus imitations involves a few practical checks:

- Examine the specimen under a strong light source and with backlighting; natural iris colors typically shift with viewing angle and lighting rather than appearing as a uniform superficial coating.

- Look for continuity of banding and color within the stone. Coatings or sprayed films often sit on the surface and can be scratched or abraded away.

- Use magnification to search for micro-layering, tiny inclusions or healed fractures arranged in interference-producing orientations.

- Be cautious of enhanced stones. Some vendors treat chalcedony with dyes or thin-film coatings to mimic iridescence; such treatments may show telltale signs under magnification or when exposed to solvents.

Lapidary Techniques and How to Reveal the Iris

The way an agate is cut and finished plays a decisive role in whether its iris potential is revealed. Lapidary artists and technicians use several specialized approaches:

Orientation and Slicing

Cuts made at particular angles relative to banding are more likely to display color play. Enthusiasts often slice agates into thin slabs (a few millimeters thick) and then polish both faces to maximize translucency. Thin sections allow light to interact with internal microstructures that are otherwise masked by opacity.

Polishing and Finishing

A superb, mirror-like polish is essential. Any residual abrasions scatter light and can obliterate subtle interference colors. Lapping with progressively finer abrasives and a final polish using cerium oxide or similar compounds helps produce the high gloss needed.

Backing and Mounting

Because the iris effect often depends on light transmission, lapidaries sometimes mount thin slices against contrasting backings to accentuate color. Backlighting with LEDs or placing the slice over a lightbox can dramatically change the perceived palette.

- Common lapidary products featuring iris agate: cabochons, thin slices for display, inlays and decorative tiles.

- Artists may embed slices in resin for stability and to create jewelry or art pieces that preserve the thin, delicate structure.

Uses in Jewelry, Art and Decoration

Iris agate is most frequently used where translucency and visual interest can be appreciated. Typical applications include:

- Cabochons and pendants that allow light to penetrate thinly cut sections.

- Thin slices used as focal points in necklaces, brooches and earrings.

- Architectural or decorative panels — slices set into frames or resin blocks for display.

- Collectible slabs sold to mineral enthusiasts and museums.

Designers prize iris specimens for their ability to surprise: a seemingly ordinary slice can, with correct lighting or mounting, bloom into flashes of color. Because the effect is often subtle, pieces are typically showcased in settings that allow the wearer or viewer to manipulate light and angle.

Cultural and Historical Context

Agate has a deep and variegated human history spanning thousands of years. While “iris agate” as a descriptive term is more modern, the broader use of banded chalcedony as seals, amulets and ornamental stones extends back to ancient civilizations. Key points include:

- In antiquity, agates were carved into intaglios, cameos and protective amulets because of their durability and fine-grained texture.

- Different cultures assigned symbolic properties to agate — strength, protection, and stabilizing energies.

- The more unusual and visually striking the specimen, the more it has attracted collectors across history; iris-like effects likely intrigued lapidaries in past centuries, even if not always named as such.

Modern gem and mineral enthusiasts value iris agate both for aesthetic qualities and for its narrative: the interplay of ordinary rock-forming processes producing unexpectedly ephemeral color.

Scientific Interest and Research

While not a primary subject of mineralogical research on its own, iris agate contributes to broader scientific topics:

- Studies of banding and rhythmic deposition in agates shed light on fluid dynamics and geochemical changes in cooling volcanic systems.

- Microstructural analyses (scanning electron microscopy, thin-section petrography) can reveal the mechanisms behind interference colors — for instance, layering at sub-micrometer scales or oriented inclusions.

- Understanding natural thin-film effects helps distinguish them from anthropogenic coatings and informs conservation of natural specimens.

Beyond basic research, techniques developed to image and characterize microstructures in iris agates have analogues in materials science, where controlled thin layers and interference effects are engineered for optical devices.

Market, Collecting and Value Determinants

Not all agates labeled “iris” command high prices; value depends on several interrelated criteria:

- Intensity and quality of the iris effect — bright, shifting colors that are visible under reasonable lighting raise desirability.

- Pattern and aesthetic appeal — compelling banding, attractive color contrasts and unusual internal formations add value.

- Size and condition — larger, intact slices polished to a high finish are more sought after.

- Provenance — specimens from well-known localities or with a documented history can achieve premium prices.

- Rarity — since iris phenomena are uncommon within agate deposits, rare pieces with consistent effects are collectible.

Collectors should beware of treatments and enhancements that simulate natural iris coloration. Counterfeit methods include the application of thin metallic coatings, dyes and resin impregnation designed to mimic interference colors. Reputable dealers will disclose any treatments; independent testing (e.g., under magnification, with solvent tests, or by spectroscopy) can help verify natural origin.

Metaphysical Beliefs and Cultural Associations

Within crystal-healing and metaphysical communities, iris agate is sometimes prized for attributes related to creativity and perception. While such beliefs are not scientifically substantiated, they form part of the stone’s contemporary cultural appeal:

- Some practitioners regard iris agate as supportive of clarity and insight, helping to reveal hidden aspects of situations through the metaphor of revealing color in light.

- It is occasionally associated with emotional balance, grounding and harmonizing energies — themes common to many forms of agate.

- Collectors and artists may also project symbolic meanings onto iris specimens because of their unique and delicate optical behavior.

For those interested in the intersection of geology and human belief, iris agate exemplifies how a minor optical oddity can catalyze artistic usage and new folklore.

Care, Preservation and Ethical Considerations

Caring for iris agate objects involves standard precautions for chalcedony and quartz-based materials:

- Clean with warm water, mild soap and a soft brush; avoid harsh chemicals that could attack surface treatments.

- Avoid ultrasonic cleaners if the specimen has visible fractures, thin sections or is mounted with adhesives that may be damaged.

- Store away from prolonged direct sunlight to prevent any potential fading of dyes or organic inclusions.

- If embedded in resin, avoid solvents that might compromise the resin’s integrity.

Ethical sourcing is an increasingly important topic. Small-scale mining for decorative stones can have environmental impacts and sometimes involves informal labor practices. Buyers seeking responsibly sourced material should:

- Request provenance information and vendor transparency about collection methods.

- Support dealers who provide fair-trade assurances or work with mines committed to environmental stewardship.

Similar Stones and Common Confusions

Iris agate can be mistaken for or compared to several other iridescent or colorful materials. Key distinctions help avoid confusion:

- Opal — displays true play-of-color caused by diffraction from silica spheres; typically softer (Mohs 5–6.5) and structurally different from chalcedony.

- Labradorite — shows labradorescence derived from internal lamellar structures in feldspar, different mineral family and cleavage behavior.

- Rainbow obsidian — a volcanic glass with sheen due to inclusions or flow-related features; lacks the microcrystalline structure of agate.

- Coated or dyed chalcedony — artificial treatments can look similar; physical tests and magnified inspection can reveal surface films or dye concentrations.

Practical Tips for Collectors and Enthusiasts

If you are seeking iris agate for collection or design purposes, consider these practical recommendations:

- Inspect specimens under multiple lighting conditions: direct, diffuse, and transmitted light (backlighting) to fully appraise iris potential.

- Ask sellers for documentation of treatment and origin. Provenance increases trust and value.

- When buying a finished jewelry piece, consider how the setting either conceals or displays the thinness necessary to see the iris effect.

- For lapidary work, start with slabs and experiment with thicknesses; sometimes reducing a slab by just a millimeter or two reveals color planes.

- Join specialist forums or local mineral clubs to see specimens in person and learn from experienced collectors about specific localities and behaviors.