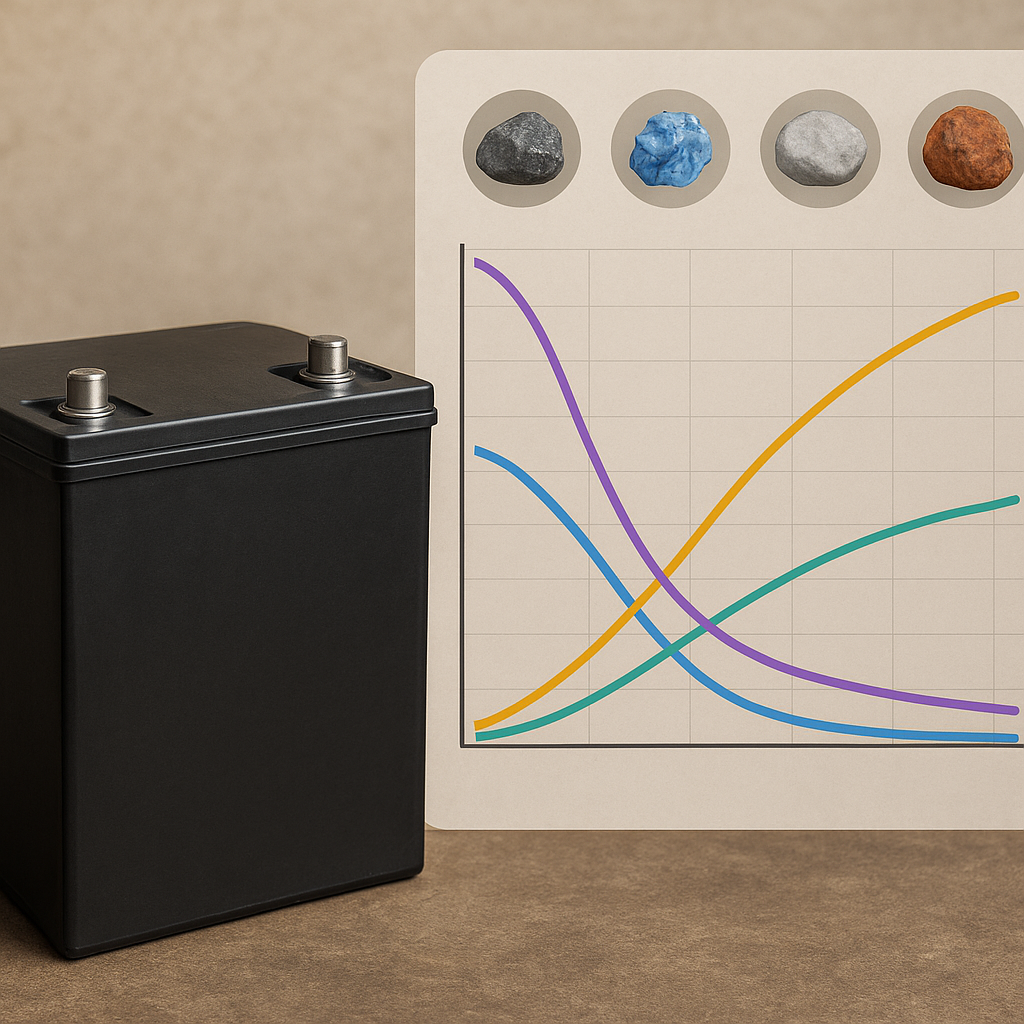

The rapid evolution of battery technologies is reshaping the global demand for raw materials. As developers pursue higher energy density, lower cost, longer life and improved safety, different chemistries change which minerals are most valuable and where supply pressure will appear. This article examines how shifting battery chemistries affect mineral needs, the geopolitical and environmental consequences, and what industry, policymakers and communities should consider to navigate the transition.

Shifting chemistries and their mineral footprints

Historically, mainstream lithium-ion batteries used combinations of lithium, cobalt, nickel and graphite in cathodes and anodes. Over the past decade, manufacturers have diversified cathode chemistries—moving from cobalt-heavy formulations toward nickel-rich or cobalt-free alternatives—and explored entirely different systems such as sodium-ion, lithium-sulfur and solid-state designs. Each chemistry reorders the ranking of critical minerals.

Common and emerging chemistries

- Lithium iron phosphate (LFP): reduces or eliminates cobalt and nickel requirements while increasing demand for iron and phosphate. LFP’s safety and cycle life make it attractive for stationary storage and some EV segments.

- NMC / NCA (nickel manganese cobalt / nickel cobalt aluminum): higher nickel variants boost energy density but inflate demand for nickel while efforts continue to lower cobalt content to improve ethics and cost.

- Sodium-ion: substitutes sodium for lithium, cutting lithium dependency. Sodium-ion cells generally use different cathode materials and may rely more on abundant transition metals but often have lower energy density.

- Lithium-sulfur and metal-air: aim for very high theoretical energy densities and use abundant sulfur or oxygen, potentially reducing reliance on heavy transition metals. Practical challenges remain in lifecycle and safety.

- Silicon-dominant anodes and advanced binders: increasing silicon content can reduce graphite demand but raise requirements for high-purity silicon and new processing chemicals.

Beyond the active electrode materials, cell manufacturing and pack assembly create steady demand for copper (current collectors, wiring) and aluminum (casings, busbars). Changes in form factor or packaging can alter those material intensities but rarely eliminate them.

Geopolitical and supply-chain implications

The minerals reshaping the battery landscape are unevenly distributed worldwide. Production concentration creates vulnerability; new chemistries shift which countries wield leverage over supply chains.

Concentration and new pressure points

- Lithium: major producers include Australia, Chile and Argentina (the “Lithium Triangle”). Broader adoption of lithium-rich chemistries continues to pressure these sources, but sodium-ion could reduce that growth trajectory.

- Cobalt: heavily concentrated in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Ongoing efforts to eliminate or reduce cobalt in cathodes stem from geopolitical risk and ethical concerns around artisanal mining and child labor.

- Nickel: supply concentrated in Indonesia, the Philippines, Russia; rising nickel demand for high-nickel cathodes motivates new mining and refining investments.

- Graphite: natural graphite mining and synthetic graphite production are dominated by a few countries, notably China; anode innovations that replace graphite will affect those markets.

- Sodium and sulfur sources are widely available globally; scalable sodium-ion or sulfur-based technologies could decentralize raw-material dependence.

As chemistries change, downstream processing and refining capacity (conversion to battery-grade materials such as hydroxide or carbonate) also becomes a strategic choke point. Countries or companies that control refining and electrode manufacturing gain disproportionate influence even when raw-mineral deposits are geographically dispersed.

Environmental, social and economic considerations

New mineral demands bring both environmental risks and opportunities. Mining for any mineral carries impacts—biodiversity loss, tailings, and water use—but the scale and location of those effects shift with chemistry trends.

Water, land use and social license

- Brine extraction for lithium in arid regions can stress water resources and affect local agriculture and ecosystems.

- Hard-rock nickel and cobalt mining often require energy-intensive processing and generate significant tailings that can pose contamination risks.

- Shifting demand toward more abundant materials (iron, phosphate, sodium, sulfur) could lower some environmental pressures but expand mining into new regions with their own conservation challenges.

Social impacts—community displacement, labor rights and benefit-sharing—remain central. Moving away from cobalt may reduce some ethical concerns, but other minerals and processing steps can create fresh social tensions if not managed responsively.

Recycling, circularity and resource efficiency

One of the most powerful levers to decouple battery growth from primary mining is improved recycling and circular design. As battery volumes grow, end-of-life streams become a valuable secondary source of critical materials.

How chemistry affects recyclability

- Cobalt- and nickel-rich chemistries yield high-value recovered metals, improving economic incentives for recycling.

- LFP cells contain fewer cobalt/nickel valuables, which can reduce recycling revenue unless regulatory or design changes mandate material recovery.

- Recycling technology must adapt: hydrometallurgical and direct recycling routes differ in efficiency depending on cathode composition.

Policies such as extended producer responsibility, recycling quotas and design-for-recycling standards can accelerate circularity regardless of the dominant chemistry. Investments in battery diagnostics, second-life markets for EV packs, and standardized pack designs improve material recovery rates and reduce primary mining pressure.

Technological drivers and industry responses

R&D choices—such as prioritizing energy density, cost, supply risk mitigation or sustainability—dictate which chemistries scale. Manufacturers, commodity producers and refiners are adapting strategies to hedge uncertainty.

- Automakers are diversifying suppliers and qualifying multiple cell formats to avoid single-point exposure (e.g., both LFP and high-nickel NMC for different vehicle lines).

- Miners are expanding portfolios: some lithium producers pursue processing capacity, while nickel and cobalt firms look to produce battery-grade hydroxides rather than raw concentrates.

- Material scientists are working on innovation that reduces use of scarce elements (low-cobalt cathodes, silicon composites instead of pure graphite) and improves lifetime to amortize mineral intensity over more operating cycles.

Standard-setting bodies and governments can accelerate favorable outcomes by aligning incentives: support for battery recycling infrastructure, subsidies for less resource-intensive chemistries in grid storage, and grants for research into low-impact extraction and processing.

Practical implications for stakeholders

The changing mineral landscape matters differently to investors, policymakers, industry leaders and communities. Below are practical steps each group can take to respond to evolving battery chemistries.

- Investors: diversify exposure across mineral types and processing stages (mining, refining, cathode manufacturing, recycling). Assess geopolitical and ESG risks associated with supply concentration.

- Policymakers: create stable regulatory frameworks that encourage recycling, require transparency in sourcing, and support R&D into alternative chemistries and less water-intensive extraction methods.

- Battery and vehicle manufacturers: qualify multiple chemistries, design for disassembly, and invest in supply-chain traceability to manage risk and comply with evolving regulations.

- Communities and civil society: demand meaningful consultation, fair benefit-sharing, and environmental safeguards when new mineral projects are proposed. Advocate for standards that protect rights and ecosystems.

Looking ahead

Emerging battery chemistries will not suddenly erase demand for any single mineral, but they will redistribute pressure across different materials and geographies. A future with mixed chemistry portfolios—combining high-density lithium-based cells for long-range EVs, LFP for grid storage, and sodium-ion or sulfur-based systems for certain applications—is plausible and likely desirable from a resilience standpoint. Building robust recycling systems, diversifying supply chains, investing in lower-impact extraction and supporting transparent governance will determine whether the material transition is managed sustainably.