Hematite is one of the most widespread and historically significant iron oxides on Earth. As both a major source of iron and a striking mineral used in pigments, jewelry, and high-tech applications, hematite connects geology, industry, art, and planetary science. This article explores where hematite occurs, how it forms, its physical and chemical characteristics, its traditional and modern uses, and several fascinating aspects that make it important to science and society.

Occurrence and geological formation

Hematite (Fe2O3) is ubiquitous in many rock types and environments. It forms through a variety of geological processes, so it is found worldwide in both primary and secondary deposits.

Primary and magmatic settings

- Hematite can crystallize directly from hydrothermal fluids in veins and replacement zones associated with igneous activity. Hydrothermal hematite often occurs with quartz, sulfides, and other oxides.

- In some iron-rich igneous rocks and skarns, hematite is a primary oxide phase that records high-temperature conditions and fluid-rock interaction.

Sedimentary and weathering environments

- One of the most important occurrences of hematite is in sedimentary deposits known as banded iron formations (BIFs). These ancient rocks, common in Archean and Paleoproterozoic shields, consist of alternating layers of silica and iron oxides including hematite and magnetite. BIFs are the principal source of iron ore globally and are crucial to understanding early Earth atmosphere and ocean chemistry.

- Weathering of iron-bearing minerals produces hematite as a residual or secondary mineral, often forming red soils, laterite crusts, and gossans above sulfide mineralization. The reddish color of many soils and sedimentary rocks is due to iron oxides, predominantly hematite.

Meteoric and planetary occurrences

- Hematite has been detected on the surface of Mars by orbiters and rovers. The presence of crystalline and fine-grained hematite is interpreted as evidence of past aqueous activity and oxidation conditions on the planet, making hematite of astrobiological and planetary-geological interest.

Notable mining regions

- Major hematite-bearing iron ore districts include the Quadrilátero Ferrífero and Carajás in Brazil, the Pilbara and Hamersley ranges in Australia, the Mesabi Range in the United States, the Labrador Trough in Canada, and the formations of India, China, and South Africa (e.g., Sishen).

Physical and chemical properties

Hematite’s defining chemical formula is Fe2O3. Its properties vary with crystal habit and grain size, which influences both identification and uses.

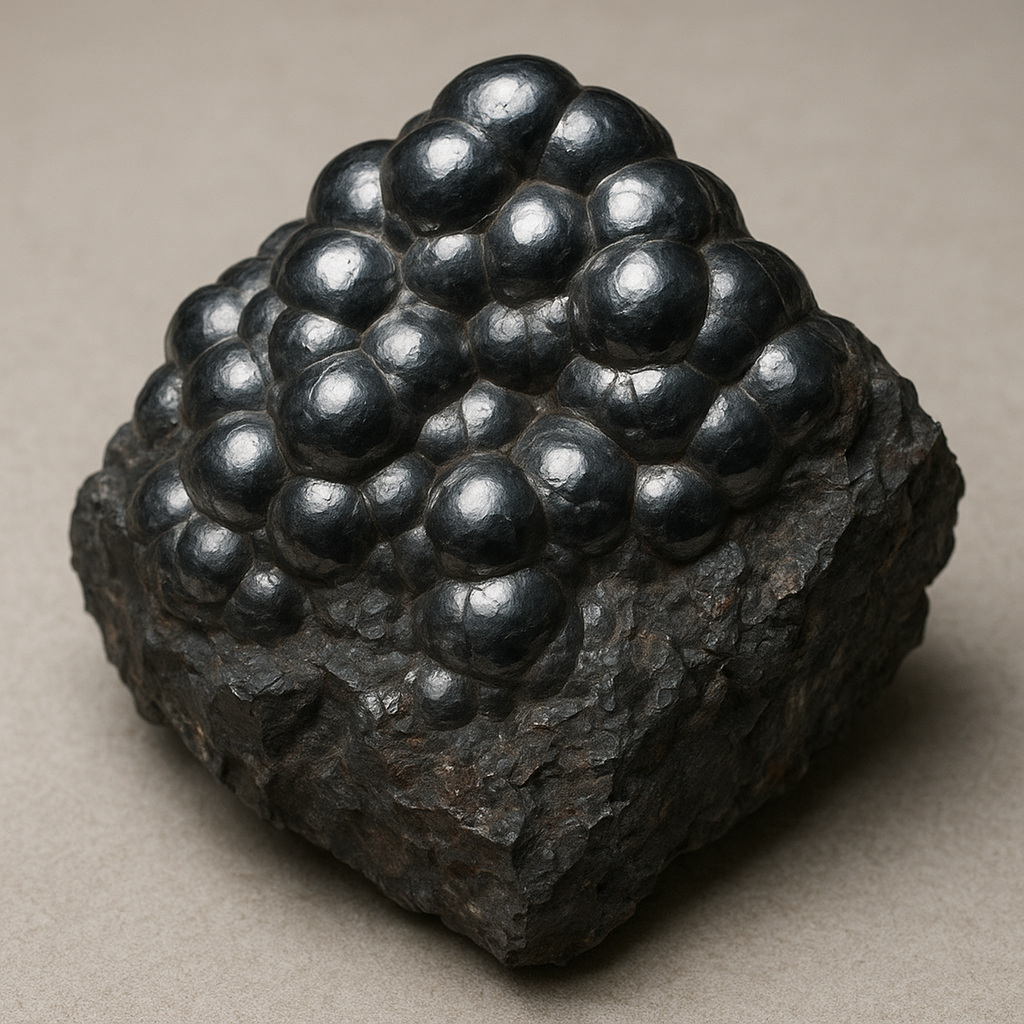

- Crystal system: Hematite crystallizes in the trigonal (rhombohedral) system. Common habits include tabular crystals, botryoidal and reniform (kidney-like) masses, earthy massive forms, and needle-like specular forms.

- Color ranges from metallic gray-black (specular hematite) to reddish-brown and deep red in earthy varieties. The streak—the color of the powdered mineral—is characteristically reddish-brown and remains a reliable field test.

- Hardness: Typically around 5.5–6.5 on the Mohs scale, making it relatively hard for an oxide mineral.

- Specific gravity: High, around 5.2–5.3, reflecting the iron content.

- Magnetic properties: Hematite exhibits interesting magnetic behavior. At room temperature it often shows weak ferromagnetism (due to spin canting). Below the Morin transition (around 250 K for pure hematite) it becomes antiferromagnetic. Finely divided hematite may show different magnetic responses, and oxidized magnetite can transform into hematite.

- Chemical stability: Hematite is the most stable of the common iron oxides under oxidizing conditions, resisting further oxidation.

Optical and spectroscopic traits

- Hematite has a relatively high refractive index in crystal form and strong absorption in the visible range, producing deep red to black colors.

- Its diagnostic spectral features (e.g., in Mössbauer spectroscopy and infrared/visible reflectance) make it identifiable in remote sensing and planetary studies.

Economic importance and mining

Hematite is among the most important iron ores used for steelmaking. Its abundance in BIFs and other deposits drives extensive mining activity and global trade in iron concentrate and pellets.

- Extraction methods vary with deposit type: open-pit mining dominates for large, near-surface BIF-hosted deposits; underground methods are used for deeper veins and replacement bodies.

- Beneficiation processes include crushing, grinding, magnetic separation (though hematite is weakly magnetic compared to magnetite), flotation, gravity separation, and upgrading to produce pellet feed or lump ore for blast furnaces and direct reduction plants.

- Brazilian and Australian hematite ores are often high-grade and require less processing, while lower-grade ores may be concentrated and pelletized for efficient steelmaking.

Uses and applications

Hematite’s uses span traditional arts to advanced technology. Its roles derive from its iron content, color properties, and stability.

- Iron and steel production: The primary industrial use of hematite is as an ore for iron, subsequently smelted and converted to steel. Hematite-rich ores are essential feedstocks for blast furnaces and direct reduction processes.

- Pigments: Ground hematite produces iron oxide pigments ranging from yellow-browns to deep reds (red ochre). Such pigments have been used since prehistoric times in rock art, pigments for pottery and paint, and in modern coatings, cosmetics, and architectural finishes.

- Jewelry and ornamental stone: Polished specular hematite and hematite cabochons are used in jewelry and beadwork. The metallic luster of specular hematite makes it popular for decorative objects.

- Polishing and abrasives: Finely powdered hematite (sometimes called “jeweler’s rouge” when very pure) is used as a polishing compound for glass and metals.

- Catalysis and environmental uses: Hematite and iron oxides are used as catalysts or catalyst supports in environmental remediation, including adsorption of contaminants, Fenton-like oxidation processes, and as electrodes in certain electrochemical treatments.

- Battery and energy applications: Nanoscale hematite has been investigated for use in lithium-ion battery anodes, supercapacitors, and as photoanodes for solar water-splitting due to its suitable band gap (~2.0 eV) and abundance. Research continues to improve conductivity and charge transfer characteristics.

- Advanced sensors and magnetic materials: Hematite nanoparticles and thin films are studied for gas sensing, magnetic recording, and spintronic applications due to tunable magnetic properties at the nanoscale.

Cultural, historical, and archaeological significance

Hematite has been used by humans for tens of thousands of years. Its vivid red pigment and metallic sheen led to symbolic and practical uses in many cultures.

- Prehistoric cave paintings and rock art frequently use red ochres derived from hematite-rich soils and rocks.

- The name hematite derives from the Greek haima (blood), reflecting the red color associated with powdered hematite; this connection has led to symbolic uses in ritual and ornamentation.

- In historic contexts hematite pigments were part of pottery slips, frescoes, and body paints. Archaeological studies of red pigments often use mineralogical analyses to identify hematite and trace trade or local production of pigments.

Scientific and technological research directions

Contemporary research on hematite focuses both on fundamental physics and practical technologies.

- Planetary science: Remote sensing identification of hematite on Mars has driven hypotheses about ancient aqueous environments and oxidation processes. Distinguishing crystalline versus microcrystalline hematite, and the context of its occurrence, is key to interpreting past environments.

- Photoelectrochemistry: Hematite is a promising, low-cost material for solar-driven water splitting as a photoanode. Challenges remain in improving charge carrier mobility, reducing recombination, and enhancing surface catalysis.

- Nanomaterials: Tailoring hematite at the nanoscale changes optical, catalytic, and magnetic properties. Synthesis of controlled morphologies—nanorods, nanotubes, and thin films—supports applications in sensing, catalysis, and energy storage.

- Magnetism and fundamental physics: Hematite is a model system for studying antiferromagnetism, weak ferromagnetism due to spin canting, and the Morin transition. These phenomena are of interest for spintronics and for understanding correlated electron behavior in oxides.

Environmental and social considerations

While hematite itself is chemically stable and relatively benign, its mining and processing have environmental and social impacts that require management and mitigation.

- Large-scale open-pit mining alters landscapes, affects biodiversity, and can produce dust and runoff. Rehabilitation of tailings and mining footprints is an important component of modern mine planning.

- Processing of ore consumes water and energy and can produce waste streams; beneficiation and pelletizing must be managed to minimize environmental footprint.

- Mining operations can affect local communities through displacement, economic shifts, and changes to traditional land uses. Best practices include stakeholder engagement, fair compensation, and sustainable development planning.

Identification and collecting

Hematite is a favorite among mineral collectors for its variety of habits and striking colors. Practical identification tips include:

- Streak test: Hematite leaves a reddish-brown streak, even when the specimen appears black or metallic.

- Specific gravity: Hematite is unusually dense for an oxide; hefting a hand sample can suggest its identity.

- Crystal habit and luster: Specular hematite has a metallic luster and plate-like crystals; earthy varieties are dull and granular; botryoidal and kidney-shaped masses show smooth rounded surfaces.

- Associated minerals: Hematite often occurs with goethite, magnetite, limonite (iron hydroxides), quartz, and sulfides, providing context for field identification.

Interesting facts and lesser-known aspects

Hematite carries many intriguing tidbits that connect science, history, and culture:

- Because powdered hematite resembles blood, it has long been associated with symbolism of life and death in art and ritual.

- Specular hematite was once used as a primitive mirror because of its metallic sheen.

- Hematite’s discovery on Mars—both in small spherules and in larger crystalline deposits—helped prioritize rover missions and informed search strategies for past aqueous environments.

- Modern nanoscience finds hematite versatile: altering particle size and doping with other elements can tune its color, conductivity, and catalytic performance.

- Formation of large-scale hematite deposits in Earth’s past is intimately tied to the rise of atmospheric oxygen and the evolution of early microbial life that influenced iron cycling.

Practical tips and safety

Hematite specimens are generally safe to handle. Fine dust from grinding or crushing can be an inhalation hazard and should be managed with appropriate dust control and respiratory protection. As with any mining or heavy-industry activity involving iron ores, occupational safety and environmental controls are important to reduce exposure and impacts.

Concluding observations

Hematite is both a common and remarkable mineral: commonplace in landscapes and soils yet central to the history of metallurgy, art, and planetary exploration. From its role in producing steel that underpins modern infrastructure to its use as a pigment that colored ancient art, hematite bridges human culture and Earth’s deep-time geochemical cycles. In the laboratory, it provides a playground for research into magnetism, catalysis, and renewable energy technologies—reminding us that a humble oxide of iron can have outsized scientific and societal importance.