Hafnium is a dense, lustrous transition metal with a reputation for being both technically vital and quietly ubiquitous in high-performance materials and advanced technologies. Chemically similar to zirconium but distinct in its nuclear and electronic behavior, hafnium has carved out a niche in fields ranging from microelectronics to nuclear engineering. This article explores where hafnium is found, how it is extracted and processed, its defining properties, and the many applications that make it an indispensable, if often invisible, contributor to modern technology.

Occurrence and Extraction

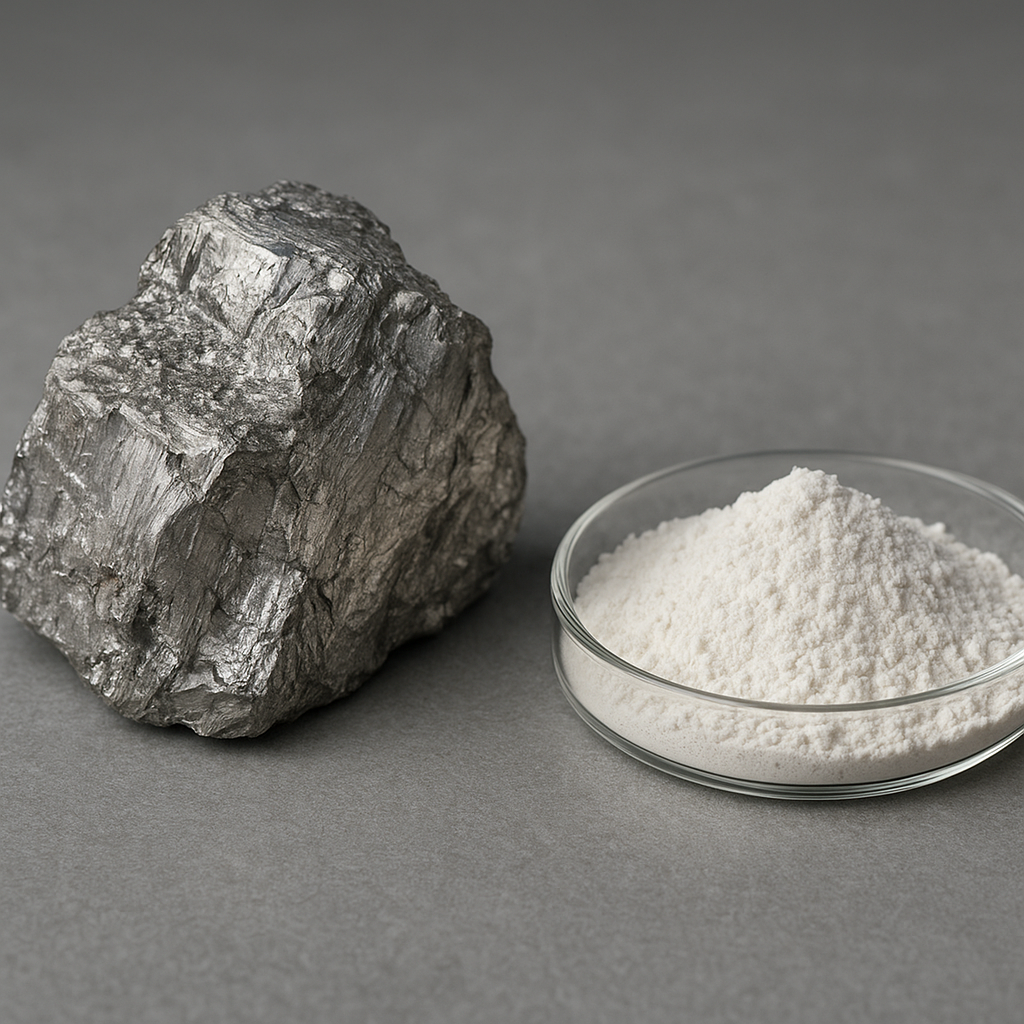

Hafnium rarely occurs as a free element in nature. Instead, it is most commonly found mixed with minerals containing zirconium. The two elements are so chemically alike that they are typically inseparable in natural deposits. Economically recoverable hafnium is mainly obtained as a byproduct of zirconium refining, where specialized separation methods extract hafnium from zirconium feedstocks.

Typical geological sources

- Heavy mineral sands and placer deposits that host zircon (ZrSiO4)

- Minerals such as baddeleyite (ZrO2) where zirconium and hafnium may substitute

- Ilmenite and other titanium-bearing sediments where zircon concentrates are processed

Commercial production typically begins with the mining of zircon-bearing sands. During mineral processing, zircon is separated and then subjected to chemical treatment to remove impurities. Because zirconium and hafnium are so similar chemically, separating them is a nontrivial step that requires careful chemical processing.

Separation and refining

The primary difficulty in hafnium production is the separation of hafnium from zirconium, which is necessary because zirconium used in nuclear reactors must be virtually free of hafnium. Hafnium has a much higher neutron absorption cross-section than zirconium, making it a contaminant in reactor structural materials but a useful absorber when isolated for control systems.

- Common industrial methods include solvent extraction and ion exchange techniques that exploit tiny differences in complexation behavior.

- Advanced hydrometallurgical processes and fractional crystallization are also used to produce high-purity hafnium metal and compounds.

- Electrolytic and metallothermic reduction (using magnesium or calcium) are typical routes to metal production from oxide or halide precursors.

Global production is limited compared to many other industrial metals. The supply chain begins in countries rich in heavy mineral sands (for example, Australia, South Africa, and certain regions of Asia), and processing capacity is concentrated among a few specialized producers.

Properties and Chemistry

Hafnium occupies atomic number 72 in the periodic table and has the electron configuration [Xe] 4f14 5d2 6s2. It is a dense, ductile metal with a silver-gray appearance and excellent corrosion resistance. Some of its physical and chemical attributes make it uniquely suited for specific demanding applications.

- Atomic weight: roughly 178.5

- Typical density: around 13 g/cm³ (heavy for a transition metal)

- Notable thermal stability and strength at elevated temperatures

What gives hafnium much of its distinctive behavior is the filled 4f shell, which imparts predictable chemistry but also contributes to complex coordination behavior in compounds. Hafnium readily forms a stable oxide layer (HfO2) that protects it from further corrosion in many environments.

Common compounds

- HfO2 (hafnium dioxide) — an extremely important oxide used as a dielectric and ceramic component

- Hafnium carbides (HfC) and borides (HfB2) — ultra-high-temperature ceramics with exceptional melting points

- Halides and organometallic hafnium complexes — used as intermediates in metal production and catalysis

Hafnium’s compounds tend to be refractory and chemically robust. For example, hafnium carbide and diboride are among the ceramics with the highest melting points known, making them attractive for extreme-temperature applications.

Applications and Uses

Hafnium’s blend of physical, chemical, and nuclear properties leads to a range of specialized applications. It is rarely encountered by the general public as a raw metal, but it plays critical roles in technologies that underpin computing, energy generation, aerospace, and materials science.

Nuclear industry

One of the most historically and industrially significant uses of hafnium is in the nuclear industry. Because hafnium has a high neutron absorption cross-section, it is an excellent material for control rods, burnable poisons, and neutron shielding components in reactors. In these roles, hafnium can quickly absorb neutrons and thereby regulate nuclear chain reactions with precision.

- Hafnium alloys and metal components are used in control rod assemblies for certain reactor types.

- Its corrosion resistance under reactor conditions helps ensure longevity and reliability.

Conversely, zirconium used for fuel cladding and reactor internals must be low in hafnium to avoid undesired neutron absorption. This dual role — as both a valuable absorber and a problematic contaminant — is one of the reasons hafnium is so strategically managed.

Microelectronics

In the realm of semiconductor technology, hafnium oxides have been transformative. During the 2000s, the industry moved away from ever-thinner silicon dioxide gate dielectrics toward materials with a higher dielectric constant (so-called high-k dielectrics) to control leakage currents while maintaining capacitance. HfO2 emerged as a leading candidate and has been widely adopted in advanced CMOS processes.

- Hafnium-based dielectrics are used in transistor gate stacks to reduce power leakage and enable further miniaturization.

- Hafnium silicates and related compounds are part of tailored gate dielectric stacks in modern integrated circuits.

This application led to a surge in demand for high-purity hafnium compounds and spurred intense research into interface chemistry, thermal stability, and thin-film deposition techniques such as atomic layer deposition (ALD).

Advanced ceramics and ultra-high temperature materials

Hafnium-containing ceramics are prized where temperatures and oxidative environments exceed the limits of conventional materials. Hafnium carbide and hafnium boride are used in experimental and niche commercial applications that demand materials stable at several thousand degrees Celsius.

- Refractory coatings and components for hypersonic vehicles, scramjet nozzles, and thermal protection systems

- Composite materials in aerospace that require oxidation resistance at extreme temperatures

- Plasma-facing components in research devices where heat fluxes are enormous

Alloys, coatings, and sputtering targets

Small additions of hafnium to alloys can improve creep resistance and high-temperature strength. Hafnium is used in superalloys and specialized nickel- and cobalt-based alloys for aerospace turbine components. Thin films of hafnium and its oxides are also deposited as optical coatings and wear-resistant layers using sputtering targets and chemical vapor deposition processes.

- Sputtering and physical vapor deposition (PVD) targets that include hafnium enable optical and protective thin films.

- Coatings that combine hafnium with other refractory elements extend component life in corrosive, high-temperature environments.

Catalysis and chemical applications

Hafnium complexes and salts have been studied for catalytic activity in polymerization and organic synthesis. Although less prevalent than catalysts based on other transition metals, hafnium catalysts display unique selectivity and thermal robustness in certain reactions.

Interesting Aspects and Recent Research

Research into hafnium and its compounds continues to be active on several fronts, often at the intersection of materials science and electronics.

Two-dimensional and quantum materials

Thin films of hafnium oxides and hafnium-based heterostructures are being explored for novel electronic phenomena, including ferroelectricity and charge trapping effects useful in non-volatile memory. The discovery of ferroelectric-like behavior in doped HfO2 thin films has opened paths to memory devices that are compatible with existing CMOS processing.

High-k gate engineering and device scaling

As transistors continue to scale, engineers optimize hafnium-based dielectrics and interfacial layers to maintain performance and reliability. This includes alloying, doping, and interface passivation strategies that reduce defects and stabilize electrical behavior under operating stresses.

Materials for extreme environments

Hafnium-bearing ceramics are part of an active research agenda focused on hypersonic flight and atmospheric reentry. Work on dense, oxidation-resistant coatings and composites seeks to overcome ablation and thermal erosion challenges at Mach speeds.

Isomeric nuclear states and medical research

Certain nuclear isomers of hafnium have been a topic of scientific curiosity. Although practical applications of these unique nuclear states are limited and require complex facilities to study, they represent an intriguing intersection of nuclear physics and materials science.

Handling, Safety, and Economic Considerations

Hafnium metal and compounds must be handled with the same precautions as other reactive metals and fine powders. In bulk metallic form, hafnium is relatively stable due to its protective oxide layer. However, finely divided hafnium powders can be pyrophoric and pose a fire risk. Many hafnium compounds are chemically inert or insoluble, but industrial safety data sheets should be consulted for specific handling and disposal guidance.

- Store metal powders under inert atmosphere or in suitable packaging to prevent ignition.

- Use standard industrial hygiene practices to limit inhalation of particulates.

- Environmental impacts are typically tied to the mining and chemical processing of zircon-bearing sands.

From an economic and strategic perspective, hafnium is a specialty material with a relatively small market size but outsized importance in certain industries. Its role in nuclear control systems and in advanced semiconductor manufacturing gives it geopolitical and industrial significance. Supply-chain considerations include the dependency on zircon feedstock availability, the concentration of refining capacity, and the evolving demand profile as new technologies adopt hafnium-based solutions.

Historical Notes and Cultural Footprint

The element was identified in the early 20th century by scientists Dirk Coster and Georg von Hevesy. They named it after the Latin name for the city of Copenhagen — Hafnia — where the discovery was made. Since its identification, hafnium has transitioned from a laboratory curiosity to a quietly essential component of modern technology.

Despite being less familiar than metals like copper or aluminum, hafnium’s influence spans critical technological domains. From the control systems that keep nuclear reactors stable to the microscopic gate stacks that make modern computing possible, hafnium plays crucial roles behind the scenes.

Further Directions and Emerging Markets

Ongoing advances in electronics, aerospace, and energy technology will continue to shape demand for hafnium and its compounds. Potential growth areas include ferroelectric memory technologies built on HfO2, next-generation ultra-high temperature ceramics for extreme aerospace applications, and tailored coatings for energy systems. As researchers push the limits of materials performance, hafnium remains a key ingredient in the toolkit for designing robust solutions to demanding engineering problems.