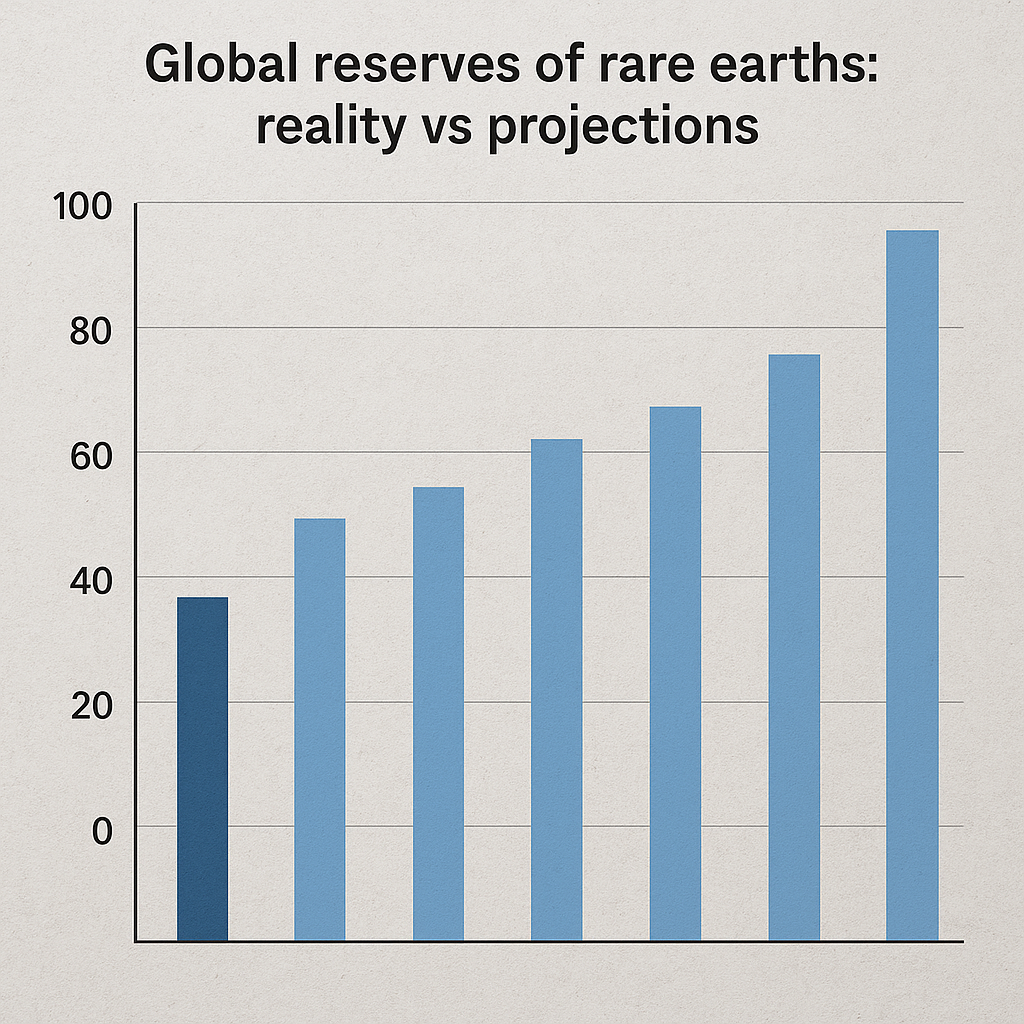

The global conversation about minerals essential for modern technology increasingly centers on the often-misunderstood category known as rare earths. Despite their name, these elements are relatively abundant in the Earth’s crust, yet their extraction, processing, and distribution present complex challenges. This article examines the difference between reported global reserves and the projections frequently cited by industry analysts, governments, and the media. It explores the technical, economic, and geopolitical factors that create divergence between what is measured, what is claimed, and what can realistically be produced to meet future demand.

Understanding reported reserves vs geological reality

Publicly reported figures for rare earth reserves typically derive from national geological surveys, company disclosures, and international agencies. These datasets classify material into categories such as resources (geological occurrences with potential economic value) and reserves (the portion that is economically extractable under current conditions). Confusion arises because many citations conflate these categories or fail to update numbers as economic, technological, and regulatory conditions change.

Key points to consider:

- Reserves are dynamic. A deposit labeled as a reserve today may fall out of that category if processing costs rise, environmental regulations tighten, or market prices fall.

- Reported numbers vary by methodology. Different countries apply distinct standards for classifying mineral concentrations, which makes cross-country comparisons difficult.

- Data latency and secrecy. Strategic considerations, proprietary company data, and limited geological surveys in some regions mean that available figures may be outdated or incomplete.

The practical implication is that headline statistics — for example, “Country X holds Y% of global reserves” — can be misleading. They are snapshots, not guarantees of long-term supply. Moreover, the concentration of refining and separation capacity in certain places further complicates the picture: even when raw ore exists in quantity, the global supply chain depends on the ability to convert ore into usable high-purity elements.

Why projections diverge from reality

Projections about future availability of rare earths hinge on a set of assumptions that are often optimistic or insufficiently transparent. Common reasons for divergence include:

- Demand growth underestimation. Emerging technologies — electric vehicles, permanent magnet wind turbines, advanced optics, and new consumer electronics — have driven sudden surges in demand for specific rare earth elements like neodymium, praseodymium, and dysprosium.

- Processing bottlenecks. The ability to mine ore is one constraint; the more critical one is chemical separation and refining. Capacity limitations here mean that physical ore reserves do not translate directly into marketable output.

- Environmental and social constraints. Strict environmental standards, permitting delays, and local opposition can curtail or delay mining and processing projects. Many rare earth ore bodies are associated with other hazardous materials, making remediation costly.

- Geopolitics. Export controls, trade disputes, and strategic stockpiling can disrupt supply irrespective of geological abundance.

- Recycling rates and substitution. Analysts sometimes assume rapid improvements in recycling technologies or substitution by other materials, which may not materialize at scale within expected timeframes.

Because projections are sensitive to these variables, scenario analyses that show widely divergent outcomes are common. A base-case projection might assume steady technological progress and moderate policy stability, while a stress-case model will show acute shortages if processing remains concentrated or if permitting becomes more onerous.

Country and company case studies: where numbers meet practice

Reality becomes clearer when looking at real-world examples. The global rare earth industry is notable for the mismatch between resource locations and processing capabilities.

China

China frequently features in headlines as the dominant actor. It holds large documented deposits and, crucially, the vast majority of global processing and separation capacity. This dominance is not simply a matter of geology but the outcome of long-term industrial policy, investment in refining infrastructure, and willingness to tolerate environmental externalities historically. Because of that integrated chain, China’s role in the market has been as much about supply control as about reserve ownership.

Australia and the United States

Both countries possess significant geological resources, and recent years have seen investments aimed at reviving domestic processing capacity. However, ramping up production requires not only extracting ore but building separation and magnet-making facilities, securing long-term offtake agreements, and meeting environmental standards. The United States and Australia illustrate how converting resources into reliable supply is a multi-year, capital-intensive process.

Smaller or emerging producers

Places such as Greenland, Russia, and parts of Africa show geological potential, but the path to becoming meaningful global suppliers is long. Challenges include poor infrastructure, political instability, and the need to develop environmentally responsible processing methods. In some cases, newly discovered resources remain undeveloped because the cost and complexity of processing rare earths outweigh potential benefits under current market conditions.

Modeling reserves: assumptions, metrics, and common pitfalls

Analysts use a variety of metrics to communicate supply-side strength. One commonly referenced metric is the reserves-to-production (R/P) ratio, which estimates how many years reserves would last at current production rates. While intuitively attractive, R/P has limitations:

- It assumes constant production, ignoring demand spikes or reductions driven by market conditions.

- It treats reserves as fully recoverable and economically viable throughout the period, which is rarely true.

- It omits the importance of processing capacity and geopolitical risk.

Better modeling approaches incorporate stochastic elements (uncertainty), scenario analysis, and supply-chain granularity. Useful practices include:

- Separating geological availability from economic availability in forecasts.

- Modeling processing and refining capacity separately from mining output.

- Including policy risk factors such as export restrictions and permitting timelines.

- Factoring in recycling penetration rates and technological substitution curves.

These methods require more data and make forecasts less tidy, but they produce projections that better reflect the range of plausible futures. It is also important to assess element-specific markets: not all rare earths behave the same way. For instance, cerium has very different demand drivers and recyclability characteristics compared to heavy rare earths like dysprosium.

Industry responses and policy options

Recognizing the gap between reported reserves and deliverable supply, governments and industries are pursuing several strategies to reduce risk:

- Investment in domestic processing. Building separation plants and magnet production lines reduces reliance on single-source suppliers.

- Recycling initiatives. Increasing the rate at which rare earths are recovered from end-of-life products can alleviate pressure on primary extraction, though technological and economic barriers persist.

- Diversification of supply chains and strategic stockpiles. Governments may maintain reserves of critical materials to cushion short-term disruptions.

- Support for research into technology that reduces rare earth content per device, enables substitution, or improves extraction efficiency.

- International cooperation to develop transparent reporting standards for reserves and processing capacity.

Each approach carries trade-offs. Building new mining and processing capacity can take a decade or more and may face environmental opposition. Recycling can help, but current recycling volumes are small relative to demand, and collection infrastructure is uneven. Substitution or reduced content in devices is possible for some applications but not for others where unique material properties are required.

Measuring progress: indicators to watch

To assess whether projections are converging toward reality, stakeholders should monitor a set of indicators rather than single metrics. Useful indicators include:

- Actual commissioning dates and output of new processing plants (not just mine openings).

- Annual material balance sheets showing primary production, net imports/exports, and recycling inputs.

- Price volatility and spreads for specific rare earth oxides, which signal supply stress.

- Permitting timelines and environmental compliance costs for new projects.

- Public and private investment flows into upstream (mining), midstream (refining), and downstream (manufacturing/magnet) segments.

Tracking these indicators helps distinguish between optimistic projections based on geological optimism and realistic supply estimates that account for industrial capacity and policy constraints.

Concluding observations

Reconciling global rare earth reserves with credible supply projections requires careful attention to the entire value chain: from ore body to refined element to manufactured component. The interplay of mining, supply chain concentration, environmental regulation, and geopolitics means that abundance on paper does not equal secure access in practice. For policymakers and companies, the prudent approach blends investment in diversified capacity, incentives for recycling, and support for innovation that reduces criticality in demanding applications. Only by moving beyond simplistic reserve tallies to integrated, dynamic analysis can stakeholders prepare for plausible futures where these essential materials continue to power technological progress with greater resilience and sustainability.