Epidote is a common yet fascinating member of the silicate mineral world, valued by geologists, collectors and occasional lapidaries for its distinctive color, crystal habits and the geological stories it tells. This article explores the mineral’s chemistry, environments of formation, practical and scientific uses, and a few intriguing aspects that make epidote more than just another green stone in the rock pile. Expect discussions of field recognition, classic localities, and why epidote often appears where fluids have altered the original rock chemistry.

Description and composition

The mineral commonly called Epidote belongs to a group of sorosilicates characterized by chains of SiO4 tetrahedra linked to octahedral sites occupied by cations such as calcium, aluminum and iron. Its general chemical formula is often written as Ca2(Al,Fe)3(SiO4)3(OH), reflecting the variable substitution between aluminum and iron that controls many of its properties. Some close relatives and compositional variants include clinozoisite (an Al-rich endmember) and manganese-bearing varieties such as piemontite.

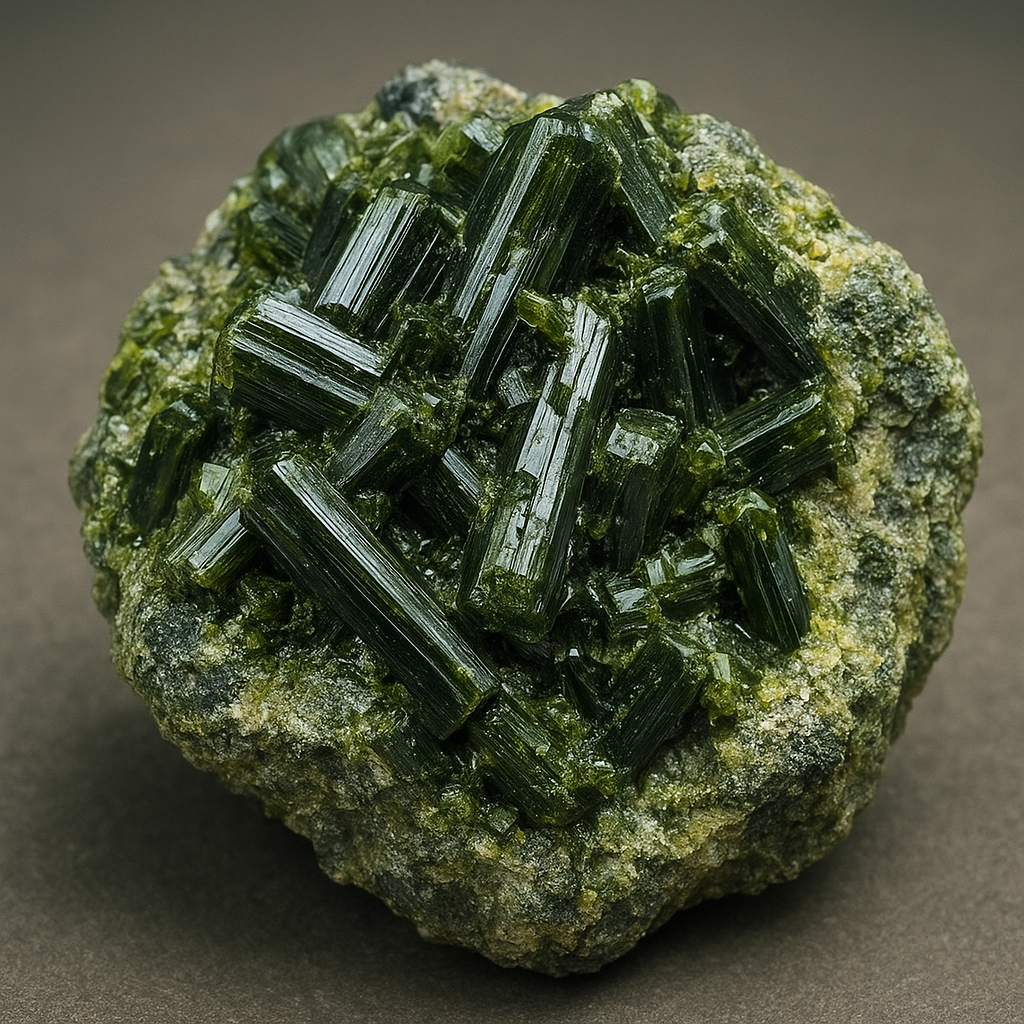

Physical appearance is practical for field recognition. Epidote typically exhibits a distinctive pistachio to yellow-green color, sometimes olive or brownish in iron-rich specimens. Many hand specimens show elongated, striated prismatic crystals with vitreous luster. Hardness generally ranges near 6–7 on the Mohs scale and specific gravity is moderate to high, often around 3.3–3.5 depending on iron content. Optical behavior in thin section shows biaxial interference, and many epidote crystals display strong pleochroism—color changes when viewed from different angles under polarized light.

Where epidote is found: geological settings and classic localities

Epidote forms in a range of geological environments where metamorphism and hydrothermal activity modify rock chemistry. Key settings include:

- Regional metamorphism of basaltic to intermediate volcanic rocks, commonly in greenschist to amphibolite facies.

- Hydrothermal veins and fracture zones, where hot fluids precipitate epidote as part of alteration assemblages.

- Contact metamorphic skarns, formed where magmas react with carbonate rocks; epidote is a frequent constituent of calc-silicate assemblages.

- Metasomatic zones and altered igneous rocks, including albitized plutonic rocks.

Because epidote forms at moderate temperatures and in the presence of fluids, it is especially common in mountain belts with complex metamorphic histories. Classic and well-known localities include alpine fissures in the European Alps (notably the Knappenwand area in Austria), parts of Norway, the Italian Alps, and pockets in Pakistan and Afghanistan that produce gemmy, translucent crystals. In North America, epidote occurs in California, Alaska and many metamorphic terranes in the western United States. Brazil and Chile supply material from hydrothermal and skarn environments. Small but attractive epidote crystals can be found worldwide wherever the right combination of calcium, silica and oxidized iron meets metamorphic fluids.

Formation processes and mineral associations

On a microscopic and chemical level, epidote records fluid-rock interaction. During prograde metamorphism of mafic rocks, original minerals such as plagioclase and pyroxene may react with infiltrating fluids to form epidote plus quartz and other phases. In contact metamorphic skarns, epidote commonly associates with garnet, wollastonite, diopside and magnetite, forming during decarbonation and silicate exchange reactions.

Hydrothermal alteration zones often exhibit epidote together with chlorite, sericite, calcite and quartz. Because it can develop under a wide range of pH and oxygen fugacity conditions, the presence of epidote is sometimes used to infer the chemistry of alteration fluids. In many ore systems, epidote occurs adjacent to or within mineralized veins, providing important paragenetic evidence about the timing and temperature of mineralization. For example, an epidote-rich alteration halo can mark the pathway of hydrothermal fluids that later deposited metals such as gold or copper.

Uses and applications

Although epidote has no large-scale industrial applications, it is valuable in several niches:

- Gemstone and ornamental use: Transparent, well-colored crystals—especially the attractive green varieties—are sometimes faceted or cut as cabochons. Most epidote used in jewelry is collector or artisanal work rather than mass-market fashion jewelry, because consistent clarity and toughness are uncommon.

- Geological and petrological indicator: Epidote is widely used by geologists as an indicator mineral for metamorphic grade and hydrothermal alteration. Its presence in metamorphosed basalt, for example, suggests certain pressure-temperature conditions and fluid activity.

- Exploration and prospecting: In mineral exploration, epidote-bearing alteration zones may flag proximity to ore deposits. The mineral’s stability field overlaps with conditions favorable for certain types of metal transport and deposition, so mapping epidote can guide further drilling or sampling.

- Educational and collecting: Epidote crystals—particularly those with sharp form and good color—are staples of mineral collections and teaching collections, helping students visualize metamorphic and hydrothermal processes.

Identification and practical handling

Identifying epidote in the field or lab uses a mix of macroscopic and microscopic clues. Look for characteristic green hues (often described as pistachio green), prismatic, often striated crystals, brittle fracture and a vitreous to resinous luster. A streak test yields a white to gray powder. Because cleavage is not prominent, epidote typically breaks with uneven fracture.

Under the microscope, epidote’s optical properties—high relief, strong pleochroism and distinctive interference colors—help distinguish it from other green minerals like chlorite, actinolite or zoisite. X-ray diffraction and electron microprobe analysis provide definitive compositional and structural confirmation when needed.

When used as a gem or cabochon, epidote requires some care. Its moderate hardness makes it suitable for occasional wear but susceptible to scratches over time. Avoid ultrasonic cleaners for heavily fractured or included specimens and protect epidote jewelry from hard bangs that could produce cleavage or fracture damage. Common cleaning by warm soapy water and a soft brush is usually adequate.

Varieties, related minerals and nomenclature

The epidote group includes a range of compositions and named varieties. Notable among them:

- Clinozoisite: an aluminum-dominant member of the group that is often pale green to colorless and forms in similar environments as epidote.

- Piemontite: a manganese-bearing member that can be reddish to brownish and is sometimes grouped with epidote-type minerals.

- “Pistacite” or pistachio epidote: informal names used by collectors for richly green crystals prized for their color.

Taxonomy in the epidote group remains an active subject for mineralogists because cation substitutions (Fe, Al, Mn) create compositional continua rather than sharply distinct species. Modern classification increasingly leans on precise chemical analyses to assign specimens to the correct group member.

Interesting facts and modern research directions

Several aspects of epidote make it interesting beyond simple identification:

- Because epidote commonly forms by fluid-rock interaction, it serves as a natural archive of fluid compositions in mountain belts and hydrothermal systems. Isotopic studies of oxygen and hydrogen in epidote help reconstruct fluid temperatures and sources.

- Thermodynamic and experimental petrology work uses epidote stability to constrain pressure-temperature paths during metamorphism. The presence or absence of epidote in certain rock types can change with small shifts in bulk chemistry or fluid availability, making it a sensitive recorder of metamorphic history.

- In the context of mineral exploration, mapping of epidote and associated minerals with remote sensing and field spectroscopy is an evolving tool. Because epidote has characteristic spectral features, hyperspectral remote sensing can sometimes detect alteration halos on a landscape scale and focus on targets for more detailed ground work.

- Collectors prize certain well-formed epidote crystals from alpine fissures not only for color but for exceptionally elongated, terminated forms—some specimens show highly lustrous, gemmy terminations suitable for small faceted stones.

Short note on cultural and metaphysical contexts

Outside scientific uses, epidote enjoys a modest presence in metaphysical and crystal-healing communities. It is often ascribed properties related to growth, recovery and resilience—perhaps a poetic reflection of the mineral’s tendency to form during transformative geological processes. While interesting from a social and cultural perspective, such claims are outside scientific validation and should be understood as folklore rather than evidence-based fact.

Practical tips for collectors

Collectors seeking epidote specimens should consider the following:

- Look for well-terminated, translucent crystals if you want material suitable for cutting or display. Alpine fissure specimens often yield the most aesthetic crystals.

- Examine specimens for associated minerals—epidote plus quartz, calcite or garnet makes for attractive and informative samples.

- Document locality information carefully; epidote’s geology ties its appearance to specific metamorphic or hydrothermal histories, and good provenance increases scientific and collector value.

The mineral rubric around epidote is broad: it is a practical field indicator of metamorphic and hydrothermal conditions, a sometimes-beautiful gem material, and a subject of ongoing research into fluid-rock interaction, metamorphic reactions and mineral taxonomy. Its presence in rocks often signals change—a record of the chemical conversations between fluids, heat and the solid Earth. For geologists and collectors alike, that combination of beauty and information makes epidote a mineral worth recognizing and studying further.