Chalcedony is a fascinating member of the quartz family, admired for its subtle colors, fine texture and long history of human use. This article explores its natural formation, global occurrences, diverse varieties, practical and artistic applications, and cultural significance. Readers will find geological explanations, tips for collectors and lapidaries, information on synthetics and imitations, and a handful of intriguing facts that reveal why chalcedony has endured as a beloved stone through millennia.

Formation, Mineralogy and Physical Properties

Chalcedony is a form of microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline silica composed primarily of very fine intergrowths of quartz and moganite. Unlike macrocrystalline quartz, whose individual crystals are visible to the naked eye, chalcedony’s structure is so fine that it appears uniform and often waxy or vitreous in luster. Its formation typically occurs in low-temperature hydrothermal environments, in cavities of volcanic rocks, and as fillings in fractures and geodes.

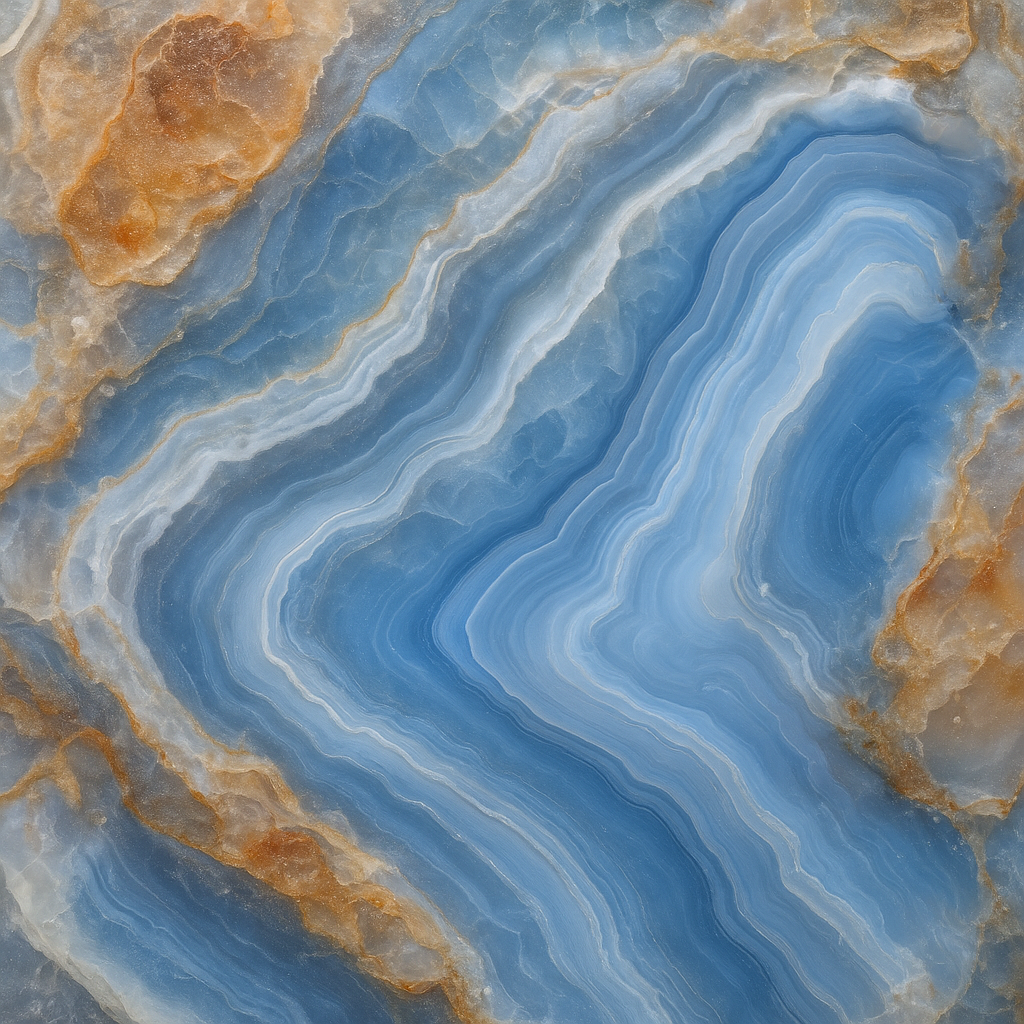

Key physical characteristics include a hardness around 6.5–7 on the Mohs scale, a specific gravity of approximately 2.6, and a conchoidal fracture. The subtle translucency of chalcedony distinguishes it from opaque varieties; when cut thinly it allows light to pass, creating a soft glow. A number of physical textures and growth habits are common: botryoidal (rounded, grape-like surfaces), stalactitic, fibrous and massive. These textural features influence both how the stone is cut and how it is valued by collectors.

Where Chalcedony Is Found

Chalcedony occurs worldwide wherever silica-rich fluids have deposited microcrystalline quartz in cavities and voids. Because of its widespread geological settings, many countries have notable deposits and distinct local varieties.

- Brazil — major source of agates and banded chalcedony, often from volcanic basalt geodes.

- Uruguay — famous for deep-colored agates and amethyst-geode associations.

- United States — states such as Oregon, Arizona, Montana and California yield agates, jasper-associated chalcedony and plume agates.

- India — large volumes of dyed and carved chalcedony, especially in Gujarat, including traditional carving material called onyx chalcedony.

- Madagascar — noted for colorful and patterned chalcedonies used in jewelry and ornamental stonework.

- Mexico — known for fire opal and chalcedony-filled pseudomorphs and Mexican lace agate.

- Botswana, Namibia and South Africa — producers of banded agates and various chalcedony materials.

Local geological settings such as volcanic flows, sedimentary basins with siliceous solutions, and metamorphic contact zones often govern the quality and appearance of chalcedony. Collectors seeking unusual patterns and colors may focus on specific localities known for unique agate banding, plume formations, or rare colors.

Varieties and Identifying Features

Chalcedony encompasses a broad family of varieties. Some are defined by color, pattern or form. Understanding these helps both collectors and jewelers identify and classify material:

- Agate — banded chalcedony with concentric or layered patterns; often found in geodes and nodules.

- Jasper — typically opaque chalcedony colored by mineral impurities (iron, manganese); valued for solid, vivid colors and patterns.

- Onyx — banded, often black-and-white or monochrome banding used classically in intaglio and cameos.

- Chrysoprase — apple-green to deep green chalcedony colored by nickel; prized for color and translucency.

- Bloodstone (heliotrope) — dark green jasper with red flecks of hematite.

- Moss and plume agates — contain dendritic or feather-like inclusions that create scenic patterns.

- Blue chalcedony — a soft, translucent blue variety used historically for beads and carvings.

Identification often combines visual inspection (banding, translucency and luster), simple tests (streak, hardness) and, when necessary, spectroscopy or microscopic analysis to distinguish natural chalcedony from glass, plastic or other silicated materials. The presence of natural, winding band patterns and subtle translucency are helpful pointers toward authenticity.

Applications: Jewelry, Art and Industry

The versatility of chalcedony has led to a wide array of applications, from refined jewelry to practical industrial uses. Its combination of durability, workability and aesthetic appeal has made it a staple material across cultures.

Jewelry and Lapidary

Chalcedony is a favorite among lapidaries because it responds well to cutting, polishing and carving. Its consistent texture allows for a high polish that emphasizes color and pattern. Common jewelry uses include:

- Cabochons for rings, pendants and earrings — especially for translucent varieties like blue chalcedony and chrysoprase.

- Cameos and intaglios carved from layered onyx or banded chalcedony.

- Beads and rosaries — a traditional use that continues in contemporary beadwork.

- Carved ornamental objects such as seals, small figurines and bookends.

Because chalcedony polishes to a subdued sheen rather than a glassy flash, it often appeals to designers seeking a soft, organic aesthetic. The stone is robust enough for everyday wear while being forgiving to complex carving work.

Historical, Decorative and Functional Uses

Historically, chalcedony has been used for signet rings, religious artifacts and decorative inlays. Ancient civilizations carved seals from it because its fine texture holds fine detail and resists wear. Decorative uses continue today in architecture accents, mosaic work, and collectible stones.

Industrial and Scientific Uses

While chalcedony is not a primary industrial mineral, its composition as silica makes it relevant in some applications: as a durable aggregate in specialized ceramics, in experimental gemstone enhancement studies, and as a subject of geological research into silica precipitation processes. Its stable chemical nature and hardness also make it useful as a standard mineral sample in educational contexts.

Care, Cutting and Lapidary Techniques

Working chalcedony requires familiarity with its fracture patterns and internal structure. Lapidaries typically use diamond tools and water-cooled laps for shaping and polishing. Steps include grinding to desired shape, pre-polishing with finer grits and final polishing with cerium oxide or tin oxide to bring out the lustrous finish.

- Store chalcedony pieces separately to avoid scratches from harder stones like diamond or corundum.

- Clean jewelry with warm soapy water and a soft brush; avoid harsh chemicals that can alter surface polish.

- Avoid thermal shock: sudden temperature changes can stress inclusions and cause fractures in nodules with internal voids.

For collectors, understanding the origin and treatments is important: some chalcedony is dyed to intensify color, stabilized with resins to fill fractures, or heat-treated. Ask sellers about treatments and, when in doubt, seek a gemological lab report for high-value pieces.

Imitations, Synthetics and Treatments

Because chalcedony is relatively affordable and attractive, imitations and treatments are common. Glass, plastic and agglomerated stone can mimic chalcedony’s appearance. Common indicators of imitation include unnatural uniform color, air bubbles (in glass), and very low hardness.

Treatments include dyeing — particularly to create vivid blues, greens or pinks — and impregnation with polymers to improve stability. Modern gemological labs can use UV, spectroscopy and magnification to detect these changes. Authentic natural specimens often show subtle variations in color and banding that are difficult to reproduce artificially.

Cultural, Historical and Metaphysical Associations

Throughout history, chalcedony has appeared in numerous cultural contexts. Ancient Greeks and Romans fashioned signet rings and intaglios from it; Islamic art often used chalcedony for seals and amulets; and in some Native American traditions, agate and jasper carried symbolic meanings.

In the realm of metaphysical beliefs, chalcedony is commonly associated with emotional balance, communication and protection. Healers and crystal enthusiasts might use chalcedony beads in meditation, suggesting that the stone soothes emotional stress and fosters harmony. While such claims are not scientifically proven, they form part of the social and spiritual value the stone holds for many people.

Collecting, Valuation and Ethical Considerations

Collectors prize chalcedony for rarity of pattern, color intensity and historical provenance. Factors that influence value include clarity, translucency, uniqueness of pattern (for agates and plumes), size and quality of polish. Rare varieties such as intense green chrysoprase or uniquely patterned plume agates command higher prices in the collector market.

- Provenance: documented origin adds value, particularly for famous localities.

- Treatment disclosure: natural, untreated stones are generally preferred and more valuable.

- Condition: chips, deep scratches or fractures lower value; excellent polish and intact patterns increase desirability.

Ethical sourcing is increasingly important. Many modern buyers seek stones sourced with fair labor practices and minimal environmental impact. Look for suppliers willing to discuss mining practices, local community benefits and transparency about treatments.

Interesting Scientific and Artistic Facts

- Chalcedony’s fine-grained microstructure can only be resolved with high-power microscopy and sometimes X-ray diffraction, revealing the intergrown quartz and moganite phases.

- Some ancient cylinders and seals carved from chalcedony survive in museum collections with remarkable detail because the stone wears slowly and holds engraving sharply.

- In the 19th century, chalcedony was popular in Victorian jewelry for hairwork lockets and mourning pieces, prized for its subtle colors and gentle translucency.

- Certain agate formations can take millions of years to develop, recording changes in mineral chemistry and temperature as layered bands. These bands can be read by geologists much like rings in trees, offering clues about ancient environments.

- Artists today use chalcedony in contemporary sculpture and inlay work where its muted glow provides a contrast to metals and glass.

Practical Tips for Buyers and Enthusiasts

When purchasing chalcedony, whether as a collector, jewelry buyer or lapidary material, consider these practical steps:

- Ask for origin information and treatment disclosure—vendors who are transparent are more trustworthy.

- Examine stones under different lighting: chalcedony’s translucency often reveals itself with backlighting.

- For mounted jewelry, consider the setting: bezel settings protect softer edges, while prongs may expose delicate cabochon edges to knocks.

- Buy from reputable dealers and, for higher-value pieces, request a gemological report that notes treatment and identification.

Further Reading and Study

Those who want to explore chalcedony further can consult geological texts on silica mineralogy, lapidary manuals detailing cutting and polishing methods, and museum catalogs that showcase historical uses. Gemological institutes often publish articles on identification techniques and treatment detection that are especially useful for serious collectors.

Suggested Topics to Explore

- Comparative studies of agate banding patterns across global localities.

- The role of trace elements (nickel, iron, manganese) in producing chalcedony color variations.

- Traditional carving techniques in India and their evolution with modern tools.

- Non-destructive testing methods for treatment detection.

Chalcedony’s blend of scientific interest and aesthetic appeal ensures its continued presence in collections, workshops and galleries. Whether approached from the perspective of geology, craft, or cultural history, it is a material that rewards closer observation and study for its subtleties and stories.