Chalcedony is a quietly fascinating mineral that sits at the crossroads of geology, art, history and culture. Its subtle translucency, pastel colors and capacity for fine polishing have made it a favorite of artisans and collectors for millennia. This article explores what chalcedony is, how and where it forms, the many ways humans have used it, and interesting facts that reveal its broader significance. Along the way you will encounter its varieties, extraction contexts, identification tips, and practical advice for those who handle or collect it.

What Chalcedony Is and How It Forms

The word chalcedony names a family of cryptocrystalline quartz composed of very fine intergrowths of the minerals quartz and moganite. At the microscopic scale the structure is tightly packed, giving chalcedony a characteristic waxy to vitreous luster and a distinctive translucency. Chemically it is silicon dioxide, or silica, and its crystalline texture is so fine that individual crystals are not visible without high magnification. Because of this texture, chalcedony is usually called microcrystalline quartz.

Chalcedony forms in a range of geological settings where silica-bearing fluids can precipitate matter into cavities or replace existing rock. Typical formation modes include:

- Hydrothermal deposition in cavities and veins where silica-rich fluids cool and crystallize.

- Volcanic contexts, such as gas cavities (vesicles) and geodes inside basalt and other lavas, where silica precipitates as the gas-filled cavities are filled with mineral-rich solutions.

- Diagenetic replacement in sedimentary rocks, where silica replaces organic or inorganic materials slowly over geological time.

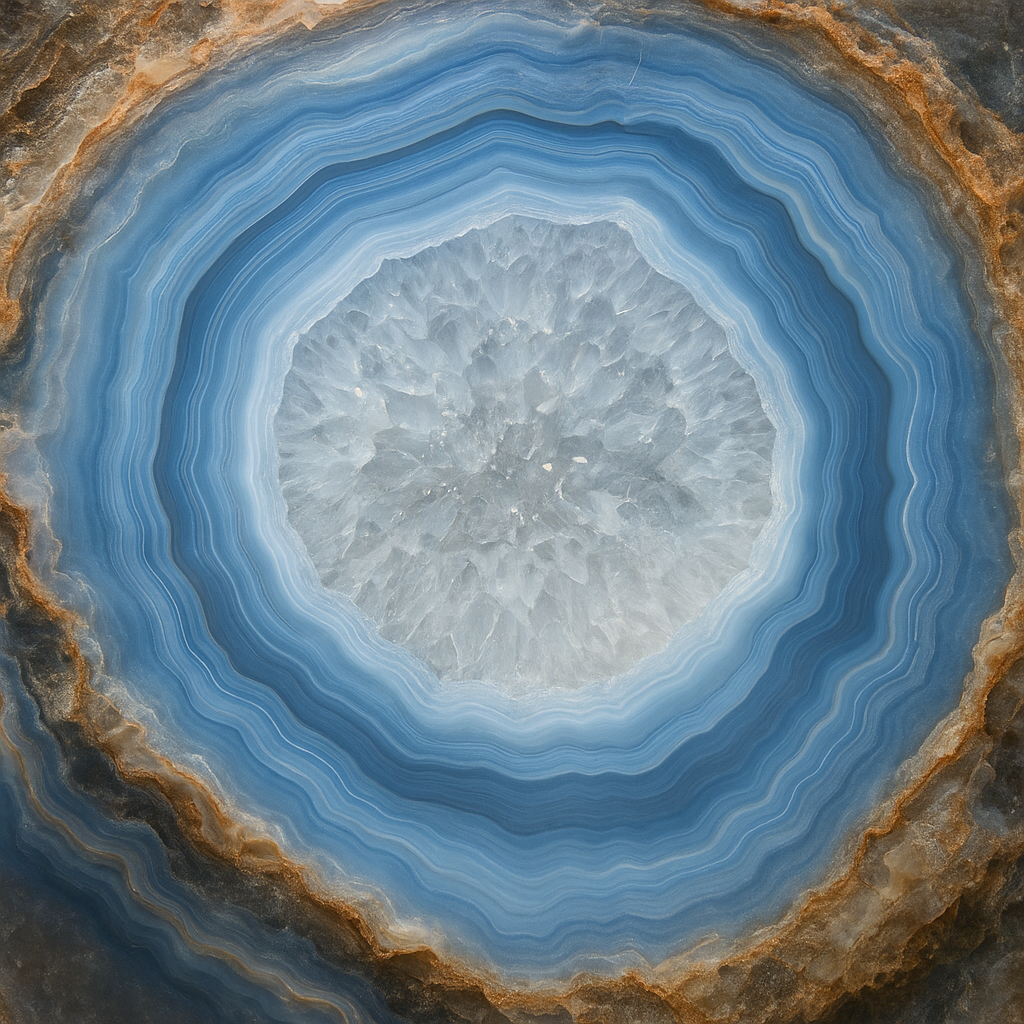

Within the chalcedony family are many recognizable varieties and trade names. Examples include banded agate, opaque jasper, translucent chrysoprase, carnelian, onyx and more specialized names like bloodstone. Banded varieties show striking layers produced by rhythmic changes in fluid composition or conditions during growth; banding is one of chalcedony’s most admired features and can produce intricate patterns.

Where Chalcedony Occurs: Global Deposits and Geological Settings

Chalcedony is globally distributed because silica is abundant in the Earth’s crust and the conditions for its precipitation are common. However, certain regions are famous for their particularly fine or unusual material.

Major producing regions

- Brazil and Uruguay: Known for large geodes and well-banded agate, often associated with volcanic rocks.

- India: A historic and contemporary source of carnelian and other beads; the Deccan Traps and surrounding regions have produced high-quality material used in jewelry for centuries.

- Madagascar: Supplies colorful chalcedony varieties including scenic and dyed materials, with modern lapidary processing creating popular cabochons.

- United States: Oregon is famous for thundereggs (filled with agate and chalcedony), while parts of Arizona, California, Idaho and New Mexico produce jasper and blue chalcedony types prized by collectors and artisans.

- Turkey and Germany: Historically important centers for cutting and trading agates and onyx; Germany’s Idar-Oberstein is well-known for its gemworking tradition.

Within these regions, chalcedony is often found filling vesicles in volcanic rock or as nodules in sedimentary formations. Agates frequently occur as concentric banded fillings of cavities, while jasper tends to be a more massive, opaque form that may result from pervasive silica replacement of host rocks.

Uses: Jewelry, Lapidary Work, and Broader Applications

Chalcedony’s combination of robustness, fine texture, and range of colors make it a versatile material. Its Mohs hardness of about 6.5–7 allows it to take a smooth polish and maintain a wearable durability, which is why it has been preferred for personal adornment and decorative objects.

Jewelry and ornamentation

- Beads and cabochons: Carnelian and other chalcedonies have been fashioned into beads for thousands of years, from Chalcolithic and Bronze Age artifacts to modern designer pieces.

- Carved objects and intaglios: In antiquity, chalcedony was commonly carved for signet rings and seals because it takes detailed incisions well and resists wear.

- Inlay and cameos: Owing to fine banding and layered colors, banded agates and onyx have been used for cameos and decorative inlays.

Lapidary arts and sculpture

The work of cutting and polishing chalcedony is a core part of lapidary practice. Lapidaries often exploit the stone’s translucency to create pieces that play with light. Techniques include cabbing, doming, carving and intricate intaglio work. Because color and banding can vary dramatically across the same nodule, skilled cutters can produce dramatically different aesthetics from a single rough piece.

Industrial and practical roles

While chalcedony’s primary human value is ornamental, silica minerals in general have broad industrial importance. Chalcedony itself is not widely used as raw industrial silica, but in some local contexts low-grade chalcedony can be used as aggregate, and historically certain forms were fashioned into tools and scrapers prior to metal adoption. In modern times, its role remains primarily in jewelry, art and lapidary education rather than heavy industry.

Traditional and contemporary metaphysical uses

Chalcedony varieties are often attributed with healing and protective properties in many cultural traditions. Carnelian is associated with vitality and courage; chrysoprase with renewal and calm. These uses are cultural and symbolic rather than scientifically validated, but they continue to influence demand and design in markets for spiritual and wellness jewelry. The stone’s gentle translucency and calming colors contribute to its popularity in this sphere; in trade descriptions you will frequently see mentions of metaphysical attributes.

Varieties and Visual Characteristics

Understanding chalcedony’s varieties helps collectors and consumers identify what they have and appreciate the range of possible appearances. Some prominent varieties include:

- Agate — typically banded and translucent; patterns range from concentric rings to dendritic “tree-like” inclusions.

- Onyx — banded similar to agate but with parallel bands often in white and black or white and brown.

- Carnelian — a warm orange to reddish variety, historically popular for beads and seals.

- Chrysoprase — apple-green to deep green chalcedony colored by nickel inclusions.

- Jasper — opaque, often richly colored and patterned; technically part of the chalcedony group though physically distinct in appearance.

- Bloodstone (heliotrope) — dark green jasper with red spots of hematite.

Color in chalcedony arises from trace impurities or included minerals. Iron oxides commonly produce yellow, brown and red tones, while nickel can impart green hues. The presence and arrangement of inclusions also produce dendrites, moss-like patterns and landscapes in polished stones.

Identification, Treatments and Imitations

Knowing how to identify chalcedony and distinguish it from imitations is important for buyers and collectors.

Key identification points

- Translucency: Many chalcedony types are translucent to semi-translucent—light passes through the edges of well-polished cabochons.

- Luster: A waxy to vitreous surface luster, especially after polishing.

- Hardness: A durable stone around Mohs 6.5–7; it can scratch glass and resists everyday wear.

- Fine texture: Under magnification the texture appears fibrous or cryptocrystalline rather than showing individual quartz crystals.

Treatments and enhancements

Chalcedony is often dyed to enhance or change color; carnelian has historically been heat-treated to deepen the red tones. Some banded agates are dyed or heat-enhanced to intensify band contrast. Buyers should ask sellers about treatments and expect properly described enhancements in reputable markets.

Common imitations

- Glass and slag glass can be fashioned to mimic agate banding; however, glass usually has a lower hardness and different fracture characteristics.

- Plastic or resin imitations may mimic translucency but will be lighter and softer.

- Reconstituted materials: Small fragments can be assembled with resin to make “reconstituted” agate-like slabs; such products should be clearly labeled as treated or composite.

Care, Handling and Longevity

Chalcedony is generally low-maintenance but benefits from thoughtful care to preserve appearance:

- Cleaning: Use warm, soapy water and a soft brush. Rinse thoroughly and dry with a soft cloth.

- Avoid harsh chemicals: Household bleaches or strong acids can damage or discolor some varieties or treated stones.

- Ultrasonic cleaners: Generally acceptable for stable, intact chalcedony, but avoid if the stone has surface fractures or fragile inlay settings.

- Storage: Keep pieces separate to prevent abrasion—wrap in soft cloth or store in individual compartments.

With proper care, chalcedony jewelry and ornamental objects can last generations. Its durability and polishability are reasons it remains popular for functional adornments such as signet rings and beads.

Historical and Cultural Perspectives

Chalcedony has been valued since antiquity. Civilizations from Mesopotamia and Egypt to the Roman Empire used chalcedony for seals, amulets and jewelry. The ability to carve fine detail made it ideal for signets and engraved gems used to authenticate documents. In many cultures carnelian beads and amulets were worn for protection, status or spiritual reasons.

During the Renaissance and later, chalcedony and agate were again prized for cameos, intaglios and cabinet pieces. In some regions, traditional lapidary crafts and bead-making techniques were passed down through generations, forming an artisanal heritage still practiced today.

Collecting, Market Trends and Ethical Considerations

Collectors value chalcedony for its diversity of color, pattern and the skill shown in lapidary work. Market prices depend on color saturation, pattern rarity, translucency, and the quality of the cut. Notable collector pieces—such as perfectly banded agates, rare chrysoprase, or historically significant intaglios—can command substantial sums.

Ethical considerations in chalcedony production mirror concerns in other gem and mineral trades: mining impacts on local communities and ecosystems, transparency in treatment disclosures, and fair compensation for artisanal miners. Consumers are increasingly seeking stones with clear provenance and ethical supply chains. Supporting responsible dealers and learning about the origins of pieces helps promote sustainable practices.

Interesting Facts and Lesser-Known Uses

- The phrase “bloodstone” comes from the red spots on certain jasper that resemble droplets of blood and were believed to have curative properties in folklore.

- Some chalcedony types fluoresce under ultraviolet light depending on impurities and treatments, which can be a useful identification aid.

- Idar-Oberstein in Germany became a center of gem cutting and trading by importing rough material and developing sophisticated cutting techniques that shaped modern lapidary standards.

- Because chalcedony can be worked into thin translucent slices, artisans sometimes mount slices over light sources to exploit backlighting effects in decorative displays.

Chalcedony’s understated beauty, remarkable variety and deep historical roots mean it will remain a subject of interest for geologists, jewelers and collectors. Whether appreciated for its geological story, its capacity to be carved and polished into wearable art, or its place in cultural history, chalcedony continues to offer surprises and enduring appeal.