Bismuth is an often-overlooked metal with a combination of properties that make it both scientifically fascinating and increasingly useful across industries. Although it sits near the bottom of the periodic table among the post-transition metals, its unusual physical and chemical behavior, striking crystalline forms and comparatively benign biological profile have driven renewed interest from researchers, artisans and manufacturers alike. This article explores where bismuth is found in nature, how it is extracted and processed, the many applications that take advantage of its distinctive traits, and several intriguing historical and scientific vignettes connected to this remarkable bismuth atom.

Occurrence, Mining and Extraction

Bismuth is considered a relatively scarce element in the Earth’s crust compared to common metals, but it is widely dispersed and frequently found together with other metal ores. It rarely occurs as the primary ore; instead, it is often recovered as a by-product from the processing of lead, copper, tin and tungsten deposits. Major modern producers have included China, Mexico, Peru and Bolivia, though deposits are also known in Europe and Canada.

Geological environments and ore minerals

Typical minerals that host bismuth include bismuthinite (Bi2S3), bismite (Bi2O3) and various sulfosalts where bismuth substitutes into complex structures. These minerals form in hydrothermal veins and in association with sulfide mineralization. The metal can also be concentrated in polymetallic veins and in some skarn-type deposits. In pegmatites and granitic systems, bismuth is less common but may appear in late-stage mineralization phases.

Recovery methods

Because bismuth is often a by-product, its recovery depends on the metallurgy used to treat the principal ore. Typical steps include:

- Roasting or oxidation of sulfide concentrates to liberate bismuth-bearing compounds.

- Hydrometallurgical leaching, often with acidic solutions, to dissolve bismuth selectively.

- Solvent extraction, precipitation and electrolytic refining to separate and purify bismuth metal.

Economically viable primary bismuth mining is rare; most supply originates from integrated smelters that extract bismuth after refining other metals. Recycling of bismuth-containing products and alloys is another growing source.

Physical and Chemical Properties

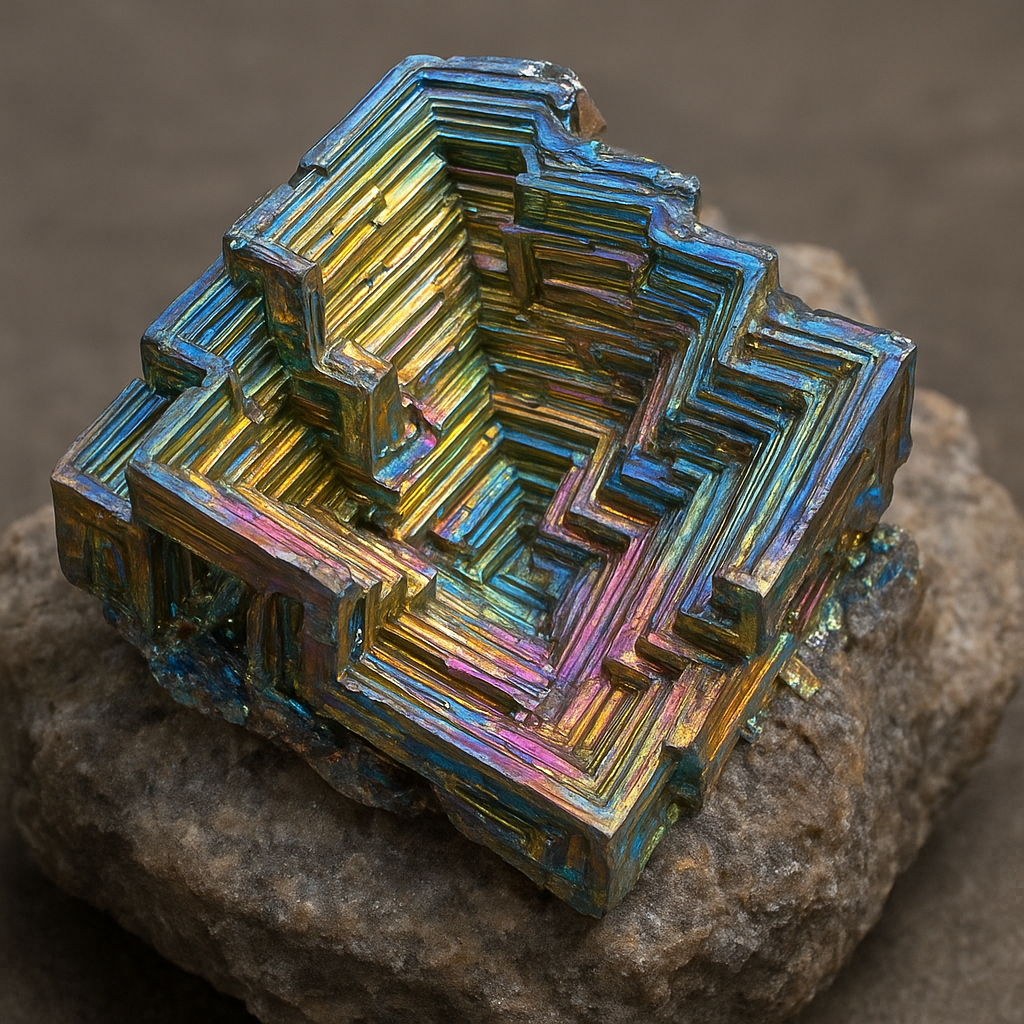

Bismuth occupies a unique niche among metals. It is brittle and crystalline at room temperature, with a silvery white appearance that often takes on iridescent tints due to surface oxidation. Chemically, bismuth shows a stable +3 oxidation state in most compounds, while the +5 state is less common and usually observed only under strong oxidizing conditions. One of its most striking physical features is its anomalously high electrical resistance compared to other metals and its unusual thermal conductivity behavior at low temperatures.

- Density and weight: Bismuth has a relatively high density (about 9.78 g/cm3), making it heavier than many common metals but lighter than lead.

- Low thermal conductivity compared to many metallic elements, yet with interesting temperature-dependent changes that have been studied for fundamental physics.

- Diamagnetism: bismuth is strongly diamagnetic among elemental metals, which leads to spectacular demonstrations such as magnetic levitation of small bismuth pieces over strong magnets.

- Crystal habit: when solidified slowly, molten bismuth readily forms intricate hopper and step-like crystals with vivid oxide colors—these are favored by artists and collectors.

From the electronic standpoint, bismuth is a semimetal with a very small overlap between valence and conduction bands. This gives it low carrier density and extremely long electron mean free paths at low temperatures, properties exploited in specialized electronic and thermoelectric research.

Applications and Uses

Bismuth’s combination of low toxicity (relative to lead), low melting point, distinctive alloying behavior and unusual electronic properties has led to a surprisingly wide range of applications in medicine, metallurgy, electronics, cosmetics, catalysts and the arts. Below are significant areas where bismuth contributes value.

Medicine and pharmaceuticals

One of the most well-known medical uses of bismuth is in compounds used to treat gastrointestinal ailments. Bismuth subsalicylate is the active ingredient in several over-the-counter remedies for upset stomach, diarrhea and dyspepsia. Other bismuth compounds have been used to treat H. pylori infections in combination therapy. The metal’s comparatively low biological toxicity (when used correctly) makes it a safer alternative to more hazardous heavy metals previously used for similar purposes.

- Antimicrobial properties: certain bismuth complexes exhibit antimicrobial activity, and researchers continue to investigate their potential as components in coatings or wound dressings.

- Radiological agents: radioactive isotope variants and bismuth-containing compounds have been studied in diagnostic and therapeutic nuclear medicine contexts.

Alloys, solders and metallurgy

Bismuth forms low-melting alloys with other metals—many of which are prized for their predictable melting points and non-toxicity compared with lead-containing solders. Examples include bismuth-tin and bismuth-indium alloys used as lead-free solder alternatives in plumbing, electrical work and fusible plugs (safety devices that melt at a set temperature to prevent fires or pressure build-up). Bismuth’s tendency to expand on solidification (an unusual trait shared with water and solid antimony in certain conditions) makes it useful for casting precision parts and as a substitute for hazardous lead-based materials in applications requiring a dense but safer metal.

Electronics, semiconductors and thermoelectrics

Because of its semimetallic nature and low carrier density, bismuth and its compounds have found niche use in electronic research. Bismuth telluride (Bi2Te3) is a prominent thermoelectric material used in cooling and power-generation devices; it converts temperature differences into electrical voltage and vice versa. Research into topological insulators—materials with insulating bulk and conductive surface states—has highlighted bismuth compounds as model systems due to their strong spin-orbit coupling.

- Bismuth telluride is a leading commercial thermoelectric for near-room-temperature applications.

- Thin films and nanostructures of bismuth compounds are studied for potential quantum electronic applications.

Cosmetics, pigments and artists’ materials

Bismuth oxychloride and related compounds have been used in cosmetics for their pearly luster and safe profile compared to contaminated alternatives. Artists enjoy bismuth crystals for their geometric hopper shapes and iridescent surfaces; melted and cast bismuth forms are often sold as decorative specimens. Pigments that contain bismuth derivatives can provide metallic sheen without the toxicity concerns associated with mercury or lead-based pigments.

Fire safety, fuses and refrigerants

Fusible alloys containing bismuth are used in safety devices that require predictable melting points, such as fire sprinkler systems, fire suppression plugs, and certain types of thermal fuses. Historically, bismuth compounds were also studied as components in refrigerant formulations, though environmental concerns and chemistry have limited some applications.

Environmental, Health and Safety Considerations

One of bismuth’s selling points is its relative environmental and biological benignness compared with heavy metals like lead, mercury and cadmium. Bismuth is often marketed as a safer alternative in consumer products and medical applications. Nevertheless, safety depends on form, dose and route of exposure; certain bismuth salts and nanoparticles require careful handling in industrial contexts.

- Bioavailability: elemental bismuth has low solubility and limited uptake in the human body; many bismuth salts are poorly absorbed, reducing systemic toxicity.

- Toxicity reports: while rare, overexposure to some bismuth compounds can lead to adverse effects such as encephalopathy when used inappropriately or at high doses. Medical formulations are regulated to avoid such risks.

- Environmental fate: bismuth tends to bind strongly in soils and sediments; however, mining and processing residues must be managed to prevent localized contamination.

Isotopes, Nuclear Properties and Research Uses

Elemental bismuth has several isotopes, the only stable isotope in nature being 209Bi, which until the late 20th century was considered absolutely stable. Subsequent measurements established that 209Bi is very slightly radioactive, with an extremely long half-life (far longer than the age of the universe for practical purposes), making it effectively stable for most applications. Artificially produced isotopes of bismuth are used in research and certain medical applications.

In nuclear physics research, bismuth has interesting roles because of its heavy nucleus and availability; it has been used in target materials and as a reference in various experimental setups. In addition, bismuth compounds have been investigated as potential converters or shielding components in specialized nuclear contexts due to their high atomic number and density.

History, Cultural Uses and Curious Facts

Bismuth has been known since ancient times but was often confused with tin and lead. The name likely comes from the German word “Wismut” (white mass), and it was systematically distinguished in early modern chemistry during the 15th–18th centuries. Historically it found minor use in alloys and small-scale medicinal preparations long before its broader technical roles emerged.

- Crystals as art: the ornate, stepped bismuth crystals produced by controlled cooling of molten metal are prized for decorative objects. The thin oxide film that forms on the surface produces a rainbow of colors, a feature exploited by artisans.

- Expansion on solidification: unlike most metals, bismuth typically expands as it freezes, which helps reduce casting defects and is useful in precision casting techniques.

- Magnetic levitation demonstrations: thanks to its strong diamagnetism, small pieces of bismuth can be levitated above strong magnets, an educational and visually impressive demonstration of electromagnetic principles.

Recycling, Supply Risk and Sustainability

Because global bismuth production is linked to the mining and refining of other metals, supply is sensitive to trends in those industries. Recycling bismuth-containing alloys and collecting by-products from electronics and specialty industrial waste streams can buffer supply constraints. As demand rises for lead-free solders and non-toxic alternatives across plumbing, electronics and consumer goods, responsible recycling and efficient extraction will be increasingly important.

Sustainable use strategies include:

- Improving separation and recovery techniques in smelters to minimize losses.

- Designing products for easier disassembly and recovery of bismuth-bearing components.

- Exploring primary deposits where environmentally acceptable mining can take place and encouraging responsible sourcing standards.

Frontiers of Research and Technological Opportunities

Contemporary scientific interest in bismuth centers on several cutting-edge areas:

- Topological materials: several bismuth-based compounds exhibit topological insulating behavior, making them platforms for quantum materials research.

- Nanostructures and catalysis: bismuth nanoparticles and bismuth-modified surfaces are being explored as catalysts in organic synthesis and in environmental remediation reactions.

- Thermoelectrics: improvements in performance for bismuth telluride-based materials continue to push their use in energy-harvesting and cooling systems.

- Biomedical engineering: targeted delivery and diagnostic agents using bismuth, including research into bismuth-containing nanoparticles with imaging contrast or antimicrobial function.

Practical Notes on Using Bismuth and Its Compounds

For hobbyists, artists and small-scale manufacturers, bismuth metal is relatively easy to work with due to its low melting point (about 271°C for pure bismuth) and attractive crystalline behavior. Common practical tips include:

- Use proper ventilation when melting to avoid inhaling fumes from fluxes or impurities.

- Employ molds and controlled cooling to produce well-formed hopper crystals; adding a small amount of tin or lead-free alloying metals changes the grain structure.

- Handle bismuth compounds with gloves and avoid ingestion; while the metal is low-toxicity relative to lead, good laboratory hygiene is essential.

Selected Interesting Case Studies

Several niche applications highlight bismuth’s versatility:

- Lead replacement in free-machining alloys: machinists have used bismuth-containing alloys that reproduce the desirable machining characteristics of leaded steels but without the environmental drawbacks.

- Medical formulations: bismuth subsalicylate’s enduring presence in consumer medicine underscores the element’s role in a public health context.

- High-performance thermoelectric modules: bismuth telluride devices power specialized cooling systems and energy recovery units in industrial and aerospace applications.

Wrapping Up the Exploration

Although bismuth is not as widely discussed as metals such as iron, copper or aluminum, its unique combination of properties—striking crystals, useful alloys, medical relevance in medicine, benign reputation relative to other heavy metals and modern roles in advanced electronic materials—ensures it remains a metal of practical and scientific interest. Continued research into bismuth-based technologies and improved recovery practices will likely expand its footprint in sustainable and high-tech applications, demonstrating that a less-celebrated element can play outsized roles across many fields.