Analcime is a distinctive mineral that sits at the crossroads of several mineralogical categories. Appreciated by collectors and studied by geologists, it raises intriguing questions about crystal chemistry, formation conditions, and industrial potential. This article explores where analcime occurs, how it forms, what it is used for, and several lesser-known but fascinating aspects of its chemistry and history.

Crystal chemistry and physical characteristics

Analcime is commonly represented by the chemical formula NaAlSi2O6·H2O, though natural specimens may contain variable amounts of potassium, calcium or other cations substituting for sodium. It occupies a curious position in the classification of framework silicates: classically treated as a member of the zeolite group because it contains water molecules in cavities within a silicate framework, but also regarded by many modern classifications as a tectosilicate closely related to feldspathoids. This borderline status has made analcime a subject of continued structural and theoretical interest.

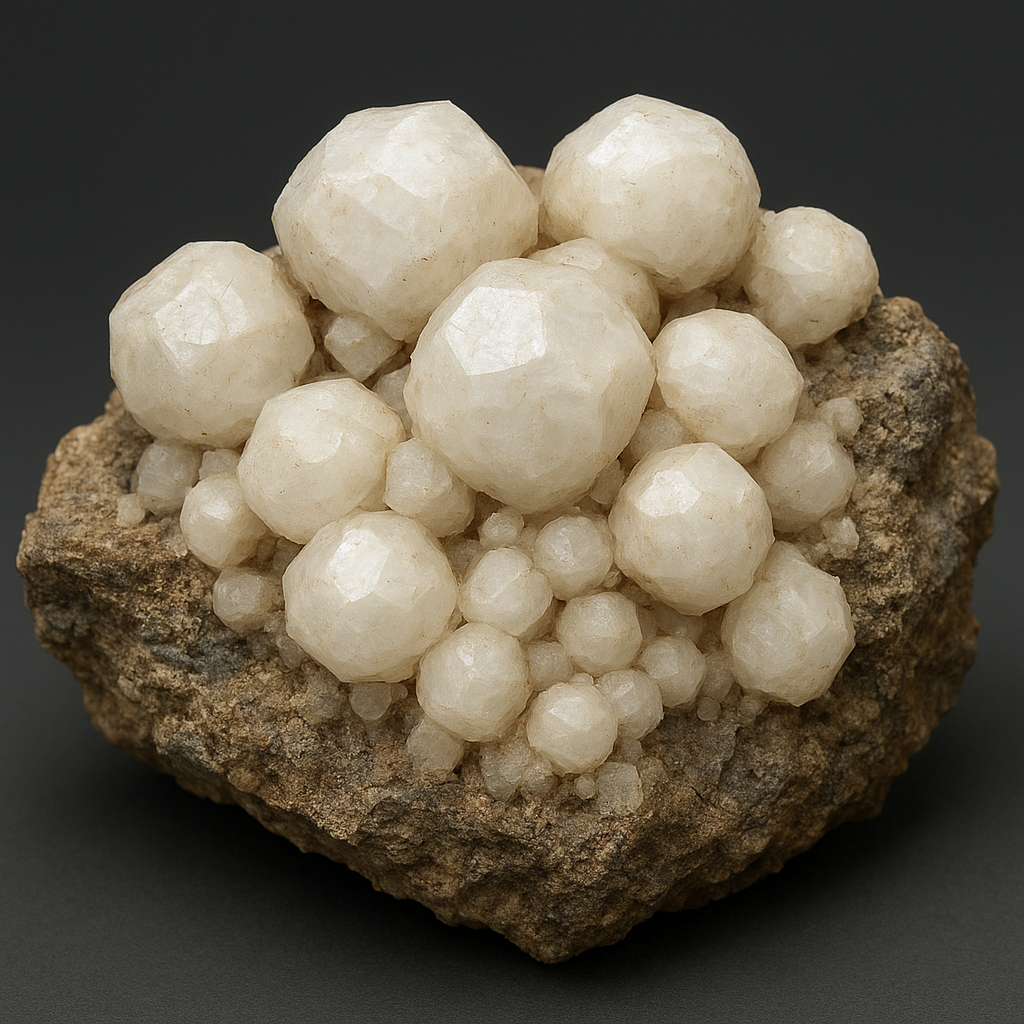

Crystals of analcime most often appear as trapezohedra or as pseudo-cubic forms and may show distortions that reduce the ideal symmetry. In hand specimen the mineral is usually colorless to white, but it commonly shows shades of gray, pink, or reddish-brown from impurities and staining. Its luster ranges from vitreous to slightly greasy, and it is typically transparent to translucent. Analcime has a Mohs hardness of about 5 to 5.5 and a specific gravity close to 2.2–2.3, making it moderate in hardness and relatively light in weight compared with many other common rock-forming minerals.

Structure and cation exchange

The analcime framework consists of linked AlO4 and SiO4 tetrahedra forming cages and channels that host water molecules and exchangeable cations. Although the channels are smaller and less open than those of many true zeolites, they still permit partial ion exchange and dehydration-rehydration behavior. This capacity to hold and release water and cations is one reason analcime attracted early attention as a zeolite analogue and why synthetic analogues are studied for adsorption and catalytic applications.

Geological environments and global occurrences

Analcime forms in a variety of geological settings, but it is most often associated with alkaline and mafic volcanic rocks. Its mode of occurrence and the minerals commonly associated with it give geologists useful clues about the temperature, composition, and evolution of the host rocks.

- Vesicles and amygdales in basaltic lavas — Analcime frequently crystallizes in cavities (amygdales) within basaltic and other mafic volcanic flows. Here it typically grows from late-stage hydrothermal fluids that circulate through the cooling rock. In these settings it is commonly associated with other zeolites, calcite, and chlorite.

- Alkaline intrusive rocks — In nepheline syenites, phonolites, and other silica-undersaturated intrusive rocks, analcime may appear as phenocrysts or as late-stage vein and cavity fillings. It can be present alongside minerals such as nepheline, leucite, and sodalite.

- Hydrothermal alteration zones — Low- to moderate-temperature hydrothermal alteration often produces analcime where fluids react with glassy volcanic material or earlier-formed feldspathoids.

- Metamorphic and sedimentary occurrences — Less commonly, analcime may form in low-grade metamorphic rocks or in diagenetic settings where alkaline fluids alter volcaniclastics or tuffs.

Prominent localities for attractive analcime crystals include classic volcanic districts in Italy (notably areas near Mount Vesuvius and other Neapolitan volcanics), Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and certain localities in the United States, Canada, and Russia. Fine, well-formed crystals have been recovered from vugs and cavities in continental basalts and from pegmatitic pockets in alkaline complexes. Collectors prize sharply formed, colorless to pink crystals that achieve centimeter scale in exceptional specimens.

Uses, applications, and limitations

Unlike many of the true zeolites that are exploited industrially for ion exchange, water purification, catalysis, or gas separation, natural analcime has seen relatively limited large-scale commercial use. Several factors contribute to this:

- Restricted channel size — The internal cavities and channels in analcime are smaller and less accessible than those found in many zeolites, limiting ion mobility and reducing its effectiveness for some adsorption and molecular-sieve applications.

- Variable composition — Natural analcime often contains significant substitution by potassium or calcium, and deposits are not as abundant or as uniform as industrial zeolite sources.

- Better alternatives — Synthetic zeolites and other naturally abundant zeolites such as clinoptilolite and mordenite often outperform analcime in commercial roles and are produced at scale.

Nonetheless, analcime is valuable in several contexts:

- Petrological indicator — Because its formation is favored under particular chemical and thermal conditions, analcime is used by geologists as an indicator mineral. Its presence suggests relatively low-temperature hydrothermal alteration in silica-undersaturated systems and can inform interpretations of magmatic differentiation and volatile evolution.

- Research and model systems — Scientists study analcime and its synthetic analogues to understand framework silicate behavior, cation-water interactions, and phase relations among feldspathoid- and zeolite-bearing assemblages. Its intermediate character between feldspathoids and zeolites makes it a useful model for structural and thermodynamic studies.

- Collector and gem material — Well-formed, transparent crystals are valued by mineral collectors. Although rare, some clean, glassy pieces are cut and fashioned into cabochons or small gems. Their low hardness limits wearability, but unusual colors and crystal forms make them attractive in specialist jewelry and lapidary applications.

- Potential niche uses — Synthetic analcime-like materials can be tailored for specific ion-exchange, catalytic, or adsorption tasks. Such engineered phases have found experimental use in environmental remediation and as catalysts, though they rarely eclipse established zeolites.

Formation processes and paragenesis

Analcime may form directly from magmatic crystallization in silica-undersaturated magmas, or it may precipitate during late-stage hydrothermal alteration of volcanic glass and primary minerals. The specific paragenetic pathway influences crystal habit, zonation, and associated minerals.

Primary crystallization

In some alkaline igneous environments, analcime crystallizes as a primary phase from the melt. It can appear as euhedral to subhedral crystals within nepheline syenites and related rocks. These primary analcimes often show chemical continuity with the host rock’s alkali budget and reflect magmatic conditions where silicon activity is lower than in typical silica-saturated magmas.

Secondary hydrothermal growth

A more common scenario in volcanic fields is the secondary growth of analcime in cavities and vesicles. Hydrothermal fluids, cooling volcanic glass, and circulating meteoric waters that have reacted with host rock can precipitate analcime along with calcite, zeolites, and clay minerals. Temperature and pH control the stability fields of analcime versus competing zeolite species; as a rule, analcime tends to form under relatively low-temperature, alkaline conditions where the sodium activity is significant.

Identification and analytical techniques

Analcime can be identified in hand specimen by its typical crystal shapes, vitreous luster, and relatively low specific gravity. However, it can resemble other white, translucent minerals, so analytical confirmation is often required.

- X-ray diffraction (XRD) — XRD provides definitive identification and can help distinguish analcime from closely related framework silicates or poorly crystalline zeolites.

- Optical petrography — In thin section, analcime may appear nearly isotropic if it displays its ideal cubic symmetry, but many natural crystals show anomalous birefringence due to structural distortions. Characteristic relief and extinction behavior, combined with association within a rock, aid identification.

- Electron microprobe and SEM — These tools allow precise measurement of major and minor elements, revealing substitutions by K, Ca, or other cations, and can image crystal morphology and zoning.

- Infrared and Raman spectroscopy — These spectroscopic methods probe water content and framework vibrations and are useful in comparing natural and synthetic samples or assessing dehydration behavior.

Historical context and mineralogical debates

Analcime has been known to mineral collectors and geologists for centuries and has played a role in the development of mineral classification. Historically lumped with zeolites because of its water-bearing framework, it later was reclassified by some workers as a feldspathoid-like tectosilicate due to its framework connectivity and compositional features. This dual identity has made analcime an instructive example in the history of silicate mineralogy, illustrating how classification schemes evolve with improved structural and chemical data.

Collectors and early mineralogists admired analcime for its often well-formed, aesthetic crystals. Significant localities produced specimens that found their way into museums and private collections, helping to spark scientific interest in volcanic and alkaline systems. Today, analcime continues to be a mineralogical touchstone for students learning about framework silicates, hydrothermal alteration, and mineral paragenesis.

Practical notes for collectors and enthusiasts

If you are a collector or a student planning to handle analcime specimens, a few practical aspects are worth knowing:

- Care and durability — With a Mohs hardness near 5, analcime is not as robust as quartz or many gemstones. Clean specimens gently with warm water and a soft brush; avoid harsh acids that can alter the surface.

- Display and storage — Because some analcime crystals can uptake or lose water with changing humidity, keep notable specimens in stable environmental conditions to preserve luster and prevent surface changes.

- Value — Most analcime is modestly priced, but unusually large, transparent, or sharply terminated crystals command higher prices among collectors. Specimens with rare colors or from celebrated localities are the most sought after.

Scientific interest and future directions

Analcime remains a subject of active research in several domains. Structural studies continue to probe the limits of framework distortions and the consequences for optical and physical properties. Synthetic analogues are investigated for specialized adsorption, catalytic, or environmental applications where unique cage sizes and exchange properties could be advantageous. In petrology, quantifying the stability fields of analcime versus other zeolites and feldspathoids helps refine models of magma evolution and low-temperature alteration processes.

Finally, analcime’s role as a bridge between classical zeolites and feldspathoids makes it valuable as a teaching mineral: it prompts discussion about classification philosophies, the interplay between composition and structure, and how subtle changes at the atomic scale produce measurable macroscopic effects. For anyone intrigued by the intersection of crystallography, chemistry, and geology, analcime offers both beautiful specimens and deep scientific questions to explore.