Pseudomalachite is a compelling and often overlooked copper mineral that frequently fools casual observers and even collectors because of its striking resemblance to the more familiar malachite. Although it shares the same verdant palette, this mineral is chemically and structurally distinct, belonging to the family of copper phosphate hydroxides. Its study illuminates the diversity of secondary mineralogy in weathered copper deposits, informs identification techniques important to miners and collectors, and provides attractive material for lapidary use despite some limitations. This article explores the mineral’s chemistry, formation, notable localities, practical applications, and other intriguing facets that make pseudomalachite a rewarding subject for both amateur enthusiasts and professional mineralogists.

Appearance, Chemistry and Crystal Structure

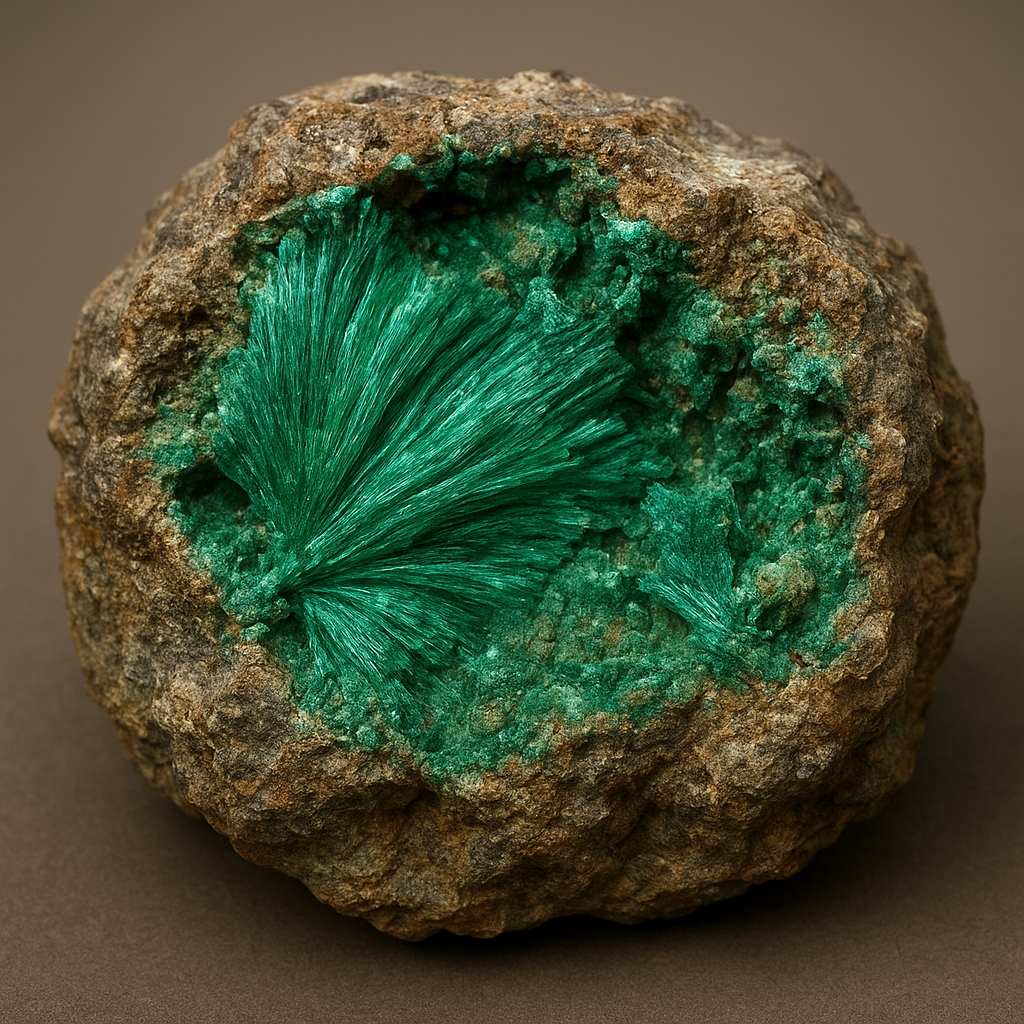

Pseudomalachite typically presents in deep green to dark green hues, often with an attractive radial, botryoidal, or massive habit that can closely mimic the banding and color of true malachite. Chemically it is a copper phosphate with the approximate formula Cu5(PO4)2(OH)4, in which copper cations are bound to phosphate groups and hydroxyls. This composition places it firmly among secondary copper phosphates rather than the copper carbonates to which malachite belongs.

Crystallographically, pseudomalachite crystallizes in the monoclinic system, but well-formed crystals are comparatively rare. More commonly it is encountered as compact aggregates, microcrystalline crusts, or botryoidal (grape-like) masses. The luster can range from vitreous to subadamantine, and specimens often exhibit a fine fibrous or radiating internal texture when examined closely.

Key physical properties that collectors and field geologists note include a moderate hardness (around Mohs 4), a characteristic green streak, and a specific gravity that is relatively high compared to many silicates because of the copper content. Under a hand lens or microscope, pseudomalachite can show distinctive radial or fibrous microstructures which are diagnostic when combined with other tests.

Formation Processes and Geological Settings

Pseudomalachite forms predominantly in the oxidation zones of copper deposits where primary copper sulfides or native copper interact with phosphate-bearing solutions. These solutions may derive their phosphate from the breakdown of phosphate-rich country rocks, hydrothermal alteration, or even biological sources such as the decomposition of organic matter and guano in some environments. In this supergene environment, copper released from primary ore minerals recombines with available phosphate anions and hydroxyl groups to precipitate copper phosphate minerals, including pseudomalachite.

The role of supergene processes is central: oxygenated meteoric waters percolate through a deposit, oxidizing primary sulfides and mobilizing copper. Where those copper-laden fluids encounter sources of phosphate and appropriate pH conditions, secondary phosphate minerals can form. These processes tend to occur near the surface or in the upper parts of ore bodies, so pseudomalachite is typically associated with the weathered caps of copper lodes and veins.

Environmental factors such as pH, redox state, and the relative abundance of competing anions (carbonate versus phosphate, for instance) influence whether copper precipitates as carbonates (e.g., malachite, azurite), phosphates (e.g., pseudomalachite, libethenite), or other species like sulfates and arsenates. This sensitivity makes the mineral a useful indicator of geochemical microenvironments within oxidized zones.

Where It Occurs — Notable Localities

Pseudomalachite is globally distributed but occurs in relatively modest abundance compared with some copper minerals. Notable localities that have produced fine specimens include:

- Tsumeb, Namibia — celebrated for its diverse and well-preserved secondary minerals, Tsumeb remains one of the most famous localities for attractive pseudomalachite specimens with excellent color and crystallinity.

- Cornwall, England — historic copper mining districts in Cornwall have yielded classic specimens, often associated with other secondary copper minerals from old workings and mine dumps.

- Arizona, USA — several copper districts in Arizona, including classic mining camps, have produced pseudomalachite; specimens are frequently recovered from oxidized mine zones and dumps.

- Germany and central Europe — early descriptions and collections of pseudomalachite came from European copper mines, where weathered ore bodies host a variety of copper phosphates.

- Katanga (DR Congo) and other African copper belts — areas of extensive copper mineralization sometimes produce interesting secondary phosphates, including pseudomalachite.

These localities are representative rather than exhaustive. Because pseudomalachite forms wherever copper and phosphate meet under suitable oxidizing conditions, it may be encountered at many copper-producing districts worldwide.

Identification and How to Distinguish Pseudomalachite from Malachite

Confusion with malachite is common because both minerals share a similar green coloration and can form botryoidal masses. However, several practical tests and observational clues help to distinguish them:

Simple field tests

- Reaction with dilute hydrochloric acid: Malachite (a copper carbonate hydroxide) effervesces readily with dilute HCl, producing bubbles of carbon dioxide. Pseudomalachite, being a phosphate hydroxide, does not effervesce with HCl. This is one of the clearest and most useful field distinctions.

- Hardness: Pseudomalachite tends to be slightly harder (around Mohs 4) than malachite (about 3.5–4). A scratch test with reference materials can help, though tests should be done carefully to preserve specimen integrity.

- Streak and luster: Both have green streaks, but subtle differences in luster and internal texture—pseudomalachite’s often more vitreous or fibrous appearance—can be diagnostic under magnification.

Analytical methods

- X-ray diffraction (XRD) and electron microprobe analysis provide unambiguous identification by revealing the crystallographic and chemical nature of the sample.

- Raman spectroscopy and infrared spectroscopy can identify phosphate functional groups and distinguish them from carbonate-bearing species.

- Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) combined with energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) offers high-resolution imaging and elemental analysis to confirm the presence of copper and phosphorus ratios consistent with pseudomalachite.

Together, field tests and laboratory analyses allow reliable differentiation between these visually similar minerals.

Associated Minerals and Typical Assemblages

Pseudomalachite is commonly found with other secondary copper minerals. Typical associates include:

- Malachite and azurite (copper carbonates) — formed under carbonate-rich conditions or adjacent microenvironments.

- Libethenite and other copper phosphates — reflecting the local phosphate chemistry.

- Chrysocolla and cuprite — common in oxidized copper zones and mine dumps.

- Adamite, brochantite, and various arsenates or sulfates where local chemistry permits.

The exact assemblage depends on subtle shifts in fluid chemistry, the presence of competing anions, and the geological history of the ore body. Studying these associations helps reconstruct the paragenesis—the sequence of mineral formation—within the weathering profile.

Practical Uses: Collecting, Lapidary Work and Beyond

While pseudomalachite is not an ore of copper in modern mining contexts, it has several practical and cultural uses:

- Collectors: Pseudomalachite is sought after by mineral collectors for its color and the way it mimics malachite. High-quality specimens with radial textures or distinct crystal faces are prized.

- Lapidary and jewelry: It is occasionally cut into cabochons or used as a decorative stone. However, its relative softness and tendency to be brittle compared to more conventional gemstones limit its mainstream use in jewelry. When used, it is typically stabilized or set in items that are not subject to rough wear.

- Educational and scientific: Because it demonstrates supergene phosphate mineralization and can be confused with malachite, pseudomalachite is valuable in teaching mineral identification, geochemistry, and paragenetic relationships in ore deposits.

- Environmental mineralogy: The occurrence of copper phosphate minerals can record aspects of the geochemical evolution of a site. In some remediation contexts, natural or induced precipitation of copper phosphates might influence metal mobility, though practical applications are specialized and not widespread.

Overall, pseudomalachite’s primary value today lies in its scientific interest and appeal to collectors and lapidaries rather than in industrial applications.

Interesting Notes, Misidentifications and Cultural Aspects

The name pseudomalachite literally means “false malachite,” reflecting taxonomic history and the mineral’s propensity to be mistaken for the much better-known copper carbonate. This naming also highlights an important lesson in mineralogy: visual similarity does not imply chemical equivalence.

Historically, specimens from old mine dumps have been mistaken in catalogs and local collections, leading to mislabeling that later research corrected. The availability of modern analytical tools—such as portable Raman spectrometers—has made field identification more reliable and has reduced longstanding confusion in many collections.

Beyond scientific circles, pseudomalachite sometimes appears in metaphysical and healing circles where green copper minerals are prized for various symbolic properties. While such uses are cultural and not scientifically supported, they have contributed to popular interest and demand for attractive specimens suitable for ornamental use.

Tips for Collectors and Conservators

- Handle specimens carefully: pseudomalachite can be brittle and may flake if struck or pried from matrix rock.

- Avoid unnecessary acid testing on museum-grade specimens; use non-destructive spectroscopic methods when possible for identification.

- Store specimens away from direct sunlight and extreme humidity; like many hydrated minerals, some copper phosphates can degrade under adverse environmental conditions.

- When used in jewelry, consider protective settings and gentle wear conditions to preserve polish and prevent fracture.

Concluding Observations

Pseudomalachite bridges practical mineralogy, lapidary appeal, and geochemical significance. Its presence in oxidized copper deposits serves as a fingerprint of phosphate-bearing fluids and supergene alteration, while its attractive green tones make it a valued specimen among enthusiasts. By understanding its chemical nature, formation context, and distinguishing characteristics—especially how it differs from malachite—one gains a richer appreciation for the complexity and beauty of secondary mineral assemblages in copper-bearing terrains.