Pallasites are one of the most visually striking and scientifically important classes of meteorites: specimens that combine translucent greenish crystals with bright metallic matrix, capturing both the imagination of collectors and the curiosity of planetary scientists. This article explores their composition, where they are found, how they form, what makes them useful for research and industry, and several intriguing aspects that make pallasites stand out among extraterrestrial rocks.

Nature and Composition of Pallasites

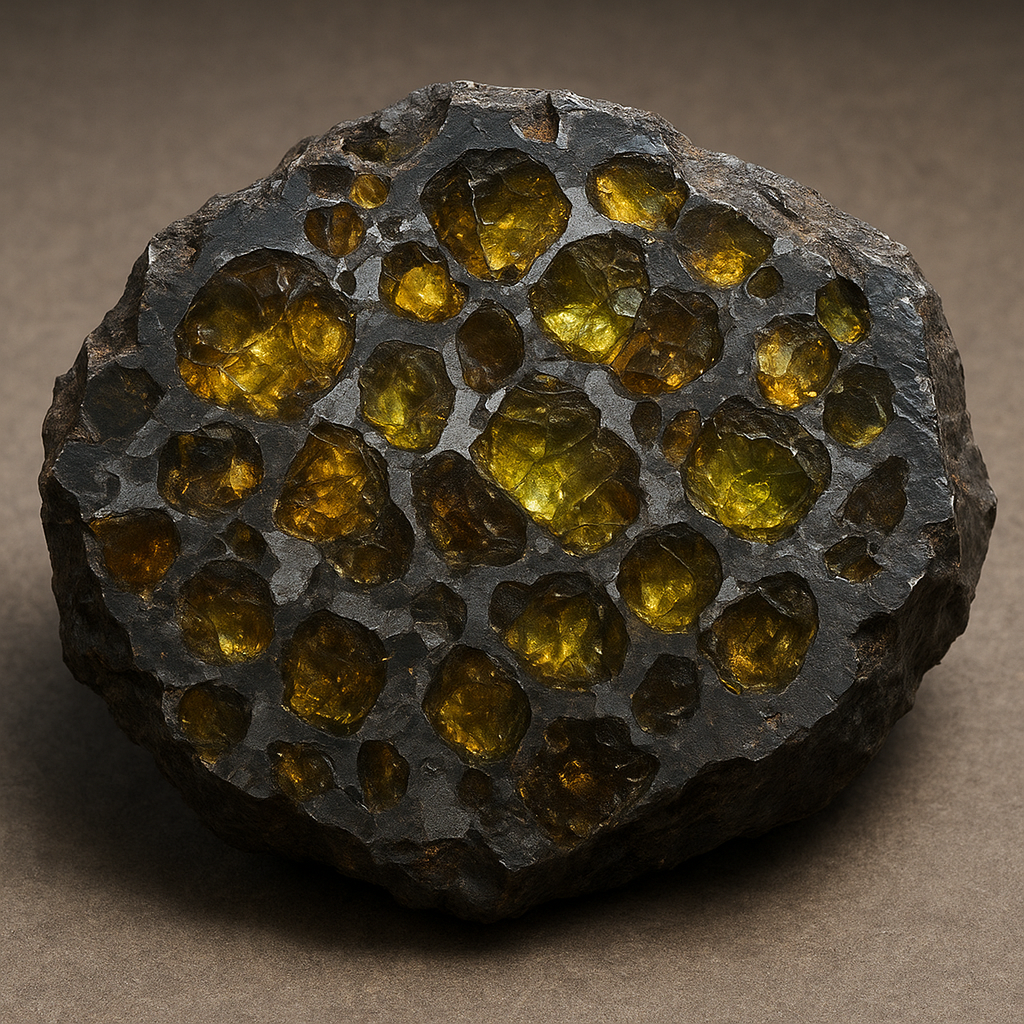

Pallasites belong to the broader group of stony-iron meteorites, characterized by an intimate mixture of silicate minerals and metal. Their most recognizable feature is the presence of gem-quality olivine crystals—commonly the mineral forsterite—embedded within a matrix of iron-nickel alloy. In polished and etched slices, the olivine crystals appear as translucent, often yellow-green to olive-colored gems set into a network of metallic host, producing a striking appearance that has made them prized by collectors and museums worldwide.

On a mineralogical level, pallasites typically contain:

- Olivine (Mg-rich, often near-forsteritic composition)

- Iron-nickel metal phases (kamacite and taenite)

- Minor phases including chromite, troilite, phosphate, and rare silicates

These meteorites often show well-preserved crystallographic textures and, under microscope, can reveal shock features, deformation in the metal, and zoning in olivine. The olivine crystals can be large—centimeter-scale in many famous specimens—and occasionally are transparent enough to be cut into cabochons or faceted gems, marketed as “space peridot” by some dealers.

Occurrence and Notable Finds

Pallasites are rare relative to other meteorite types, accounting for roughly one percent or less of all observed meteorite falls and finds. They have, however, been recovered from diverse climatic and geographic settings across the globe. Notable localities and specimens include:

- Krasnojarsk (Pallas’ discovery) — Often cited historically because Peter Simon Pallas described a large meteorite found in Siberia in the 18th century that later gave the group its name.

- Imilac (Chile) — A well-known and relatively old pallasite fall with many specimens recovered and distributed among collectors and institutions.

- Esquel (Argentina) — One of the most famous pallasites, prized for its large, gemmy olivine crystals and beautiful slices often displayed in museums.

- Fukang (China) — Discovered only in recent decades, Fukang specimens include spectacular olivine crystals and have become iconic in the meteorite trade.

- Brenham (USA) — A strewn field in Kansas with many fragments recovered over the years; metallic-dominant and often used in educational displays.

- Seymchan (Russia) — Initially found with mostly metallic material but later revealed to contain pallasitic sections; illustrates the diversity of pallasite preservation.

Most pallasite discoveries are single finds or small strewn fields rather than multiple widespread falls. Their rarity and aesthetic appeal mean that well-preserved slices with large olivine crystals command high prices on the meteorite market.

Formation Theories and the Parent Body

Pallasites are widely interpreted as samples from the boundary region between the mantle and core of a differentiated asteroid. Differentiation refers to the process by which early planetesimals separated into metal-rich cores and silicate-rich mantles due to heating and partial melting. The presence of large, sometimes euhedral olivine crystals surrounded by a continuous metal matrix strongly suggests that pallasites formed where molten metal and crystallizing silicate coexisted—an environment consistent with the interface between metal core and silicate mantle.

Competing and complementary formation models include:

- Mixing at the mantle-core boundary following impact-induced disruption and reassembly of a differentiated parent body.

- Slow cooling within a stable and layered parent asteroid, allowing metal-silicate mingling and growth of large olivine crystals at the interface.

- Local melting and injection of iron-rich melt into a partially solid silicate mantle, producing hybrid textures.

Isotope studies (oxygen isotopes, Hf–W, etc.) suggest that many pallasites share a common parentage or formation environment and are related to the so-called Main Group pallasites. However, others form distinct chemical and isotopic groupings—such as the Eagle Station group or several ungrouped pallasites—indicating multiple parent bodies or different processes of formation. The diversity in chemistry and texture implies that pallasites are not monolithic in origin, but the dominant interpretation remains their origin at or near the mantle-core boundary of differentiated asteroidal bodies.

Classification and Types

Scientists classify pallasites based on their chemistry, oxygen isotope composition, and mineralogy. The major categories include:

- Main Group pallasites — Represent the majority of known pallasites and show consistent geochemical signatures suggesting a related origin.

- Eagle Station Group — A chemically distinct cluster with different trace element and isotopic characteristics.

- Pyroxene-bearing pallasites — A small subset in which pyroxene occurs alongside olivine, offering clues about local variations in silicate composition.

- Ungrouped pallasites — Individual specimens that do not fit established groups and may represent unique parent bodies.

Classification remains active research territory; as new analytical techniques refine isotopic and elemental measurements, our understanding of pallasite linkages and their parent bodies continues to evolve.

Scientific Applications and Value

Pallasites are invaluable to planetary science because they provide a rare window into processes that shaped early differentiated planetesimals. Key scientific uses include:

- Constraining planetary differentiation: The coexistence of metallic and silicate phases in pallasites helps constrain models for core formation, metal-silicate segregation, and heat sources (e.g., radioactive decay of 26Al).

- Isotopic dating and chronology: Radiometric systems such as Hf–W, U–Pb, and cosmogenic nuclide analyses allow researchers to determine timing of differentiation, impact events, and cosmic-ray exposure.

- High-pressure experiments: Pallasite compositions guide laboratory experiments that simulate deep-planetary conditions, offering analogues to core-mantle interactions.

- Comparative planetology: Studying pallasites alongside terrestrial mantle materials and iron meteorites helps constrain bulk compositions and evolutionary pathways of small planetary bodies.

Because pallasites sample a unique geologic environment, they act as natural experiments recording thermal history, impact processing, and chemical exchange between metal and silicate. For many research questions about small-body differentiation and early Solar System chronology, pallasites are among the most informative meteorite classes.

Analytical Techniques Used on Pallasites

Modern analysis of pallasites combines classical petrography with state-of-the-art geochemical and imaging tools. Common techniques include:

- Optical microscopy and electron microprobe analysis to determine mineral chemistry and textural relationships.

- Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) for fine-scale microstructure and phase identification.

- X-ray computed tomography (XCT) to non-destructively visualize three-dimensional crystal distributions and internal structure.

- Mass spectrometry methods (e.g., SIMS, ICP-MS, TIMS) for trace element and isotopic analysis.

- Mössbauer spectroscopy and magnetic measurements to examine iron phases and cooling histories.

These analyses allow scientists to construct detailed histories for each specimen: its crystallization, subsequent shock events, cosmic-ray exposure, and terrestrial weathering. For particularly famous pallasites, multi-method studies can reveal subtle differences that change how groups are linked to parent bodies.

Practical Uses, Market, and Ethical Considerations

Pallasites have three broad domains of practical value: scientific, aesthetic, and commercial.

- Scientific: As discussed, museums and research institutions collect pallasites for long-term study and public education.

- Aesthetic and commercial: Polished pallasite slices are highly sought after. The translucent olivine nodules are sometimes fashioned into cabochons or jewelry, and large museum-quality slabs sell for significant sums. The combination of metal and crystal gives these pieces a unique visual appeal.

- Educational and outreach: Pallasite samples serve as compelling teaching specimens to illustrate planetary differentiation and the nature of meteorites in classrooms and public exhibits.

However, the market and collecting practices raise several ethical and legal issues. Laws regarding ownership and export of meteorites vary by country—nations such as Chile and Argentina have strict regulations, while many finds in desert regions are sold commercially. Provenance documentation is important for scientific integrity; once a specimen is sold without proper records, its research value may be diminished. Responsible collecting emphasizes recording find location, recovery context, and ensuring legal export/import compliance.

Cultural and Collecting Perspectives

Pallasites have long captured human attention. The historical discovery by Pallas in Siberia helped stimulate early scientific interest in meteorites and their extraterrestrial origin. In contemporary culture, pallasite slices are displayed as “space gems.” Collectors prize particularly large, transparent olivine crystals or historically significant finds.

Collecting communities often share information about new finds, but they also face tension between commercialization and science. Scientists prefer large whole specimens or well-documented falls for analysis; collectors often seek visually stunning slices. Museums sometimes collaborate with private collectors to secure access to high-quality pieces for public display or research.

Interesting and Lesser-Known Facts

- Gem-quality olivine: Some pallasite olivines are transparent enough to be faceted. Although not common in jewelry stores due to rarity and legal/ethical concerns, these “space peridots” are real and occasionally appear in private collections.

- Window into a boundary: Pallasites likely record conditions exactly where metal met silicate inside an asteroid, providing a rare natural sample of a geological boundary that otherwise requires drilling into large planetary bodies to study.

- Variable preservation: Some pallasites weather rapidly on Earth, leading to rust and olivine alteration, while others from cold deserts (e.g., Antarctic finds) can be exceptionally well-preserved.

- Market dynamics: High-quality pallasite slices from famous meteorites can fetch more per gram than many terrestrial gemstones, reflecting their rarity and collector demand.

- Scientific surprises: New analytical techniques continue to reveal unexpected variability among pallasites—differences in oxygen isotopes, trace elements, and shock histories that hint at complex formation pathways and multiple parent bodies.

Future Directions in Pallasite Research

Research on pallasites will continue to benefit from improved analytical precision and non-destructive imaging. Future directions include:

- Refined isotopic studies to better tie pallasites to specific parent bodies or dynamical families of asteroids.

- High-resolution 3-D mapping of olivine-metal textures to reconstruct cooling rates and metal flow.

- Experimental work that simulates metal infiltration into solid silicates to test competing formation scenarios.

- Integration with spacecraft data as asteroid missions return information about surface composition and internal structure of small bodies.

As remote sensing and sample-return missions expand our knowledge of asteroid diversity, pallasites will remain a vital ground truth: tangible, studied, and evocative pieces of the early Solar System that bridge the disciplines of mineralogy, geochemistry, and planetary science.