Gabbro is a coarse-grained, dark-colored igneous rock that forms a fundamental part of the Earth’s oceanic and continental crust. Its dense textures, distinctive mineral composition and broad range of occurrences make it a subject of interest across geology, engineering and industry. This article explores how gabbro forms, where it occurs, how it is used, and several related topics that illuminate its scientific and practical importance.

Origin, Composition and Formation Processes

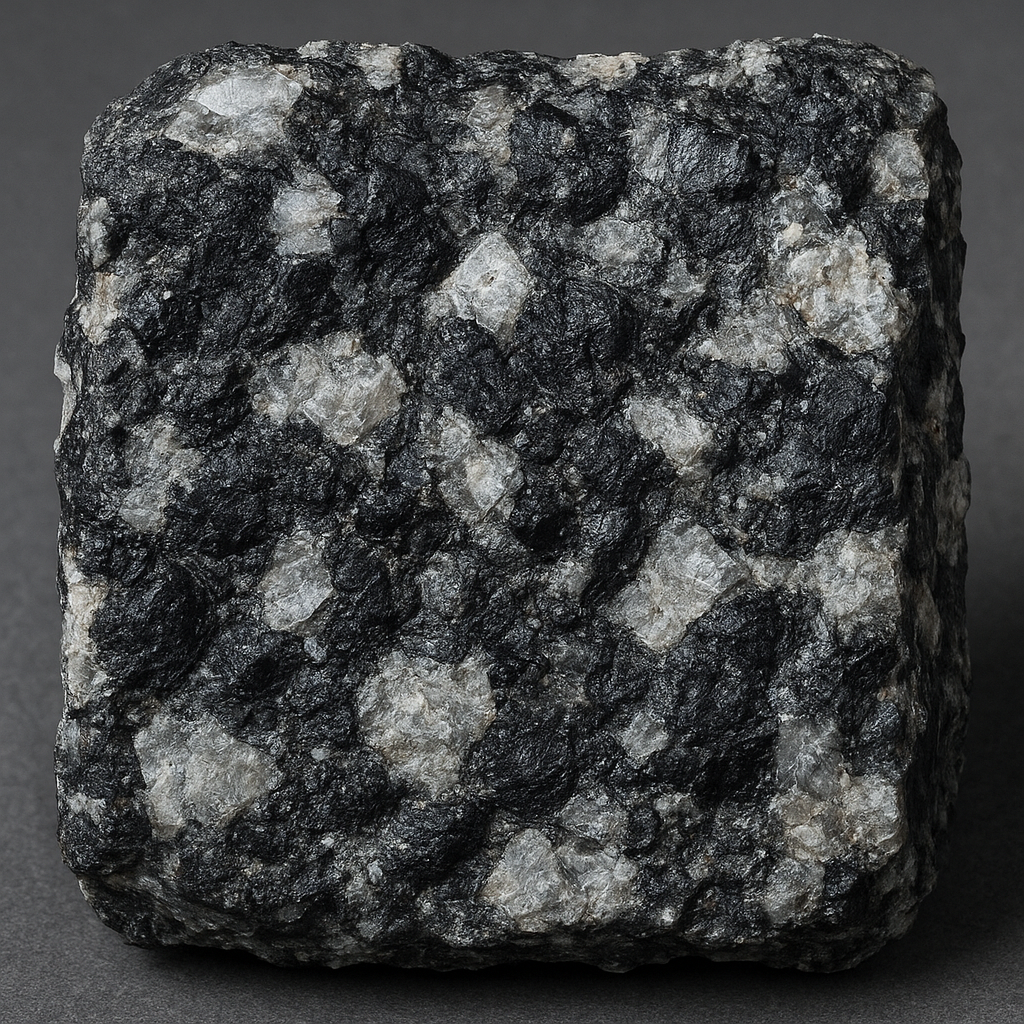

The most salient characteristic of gabbro is its mineralogy: it is a mafic intrusive rock dominated by coarse-grained crystals of plagioclase feldspar and pyroxene, with lesser amounts of olivine and accessory oxides and sulfides. Mafic denotes a composition relatively rich in iron and magnesium and poorer in silica compared to felsic rocks like granite. In chemical terms gabbro typically has silica contents around 45–52 wt% SiO2, with appreciable Fe, Mg, Ca and Al.

Gabbro forms when basaltic magma intrudes into the crust and cools slowly at depth, allowing large crystals to grow. This contrasts with basalt, which is the fine-grained extrusive equivalent produced when similar magma erupts at the surface and cools quickly. Thus, under the microscope and in hand sample, one can see that intrusive cooling regimes produce the coarse-grained textures that define gabbro, whereas rapid cooling produces the fine-grained matrix of basalt.

Crystallization and Cumulate Processes

Large magma chambers can produce gabbro by fractional crystallization, where early-formed minerals settle under gravity to form cumulate layers. These cumulate textures—zones enriched in particular minerals—are common in large layered gabbroic intrusions. In such environments, minerals may settle out in predictable sequences, producing stratified bodies where composition and texture change with depth.

Cumulate layering is especially important because it concentrates economically valuable elements. For example, sulfide liquids can segregate and collect metals such as nickel, copper and the platinum group elements, often associated with particular horizons within layered gabbroic intrusions.

Metamorphism and Alteration

Gabbro may undergo metamorphism if it is later subjected to high temperatures and pressures. Low-grade alteration often includes serpentinization where olivine and pyroxene react with water to form serpentine minerals, altering color and mechanical properties. Higher-grade metamorphism can transform gabbroic protoliths into amphibolite or granulite facies rocks, depending on pressure-temperature conditions.

Where Gabbro Occurs: Geological Settings and Notable Localities

Gabbro is ubiquitous in many tectonic settings, but it is most characteristically associated with oceanic crust and large mafic intrusions on continents. Below are the principal settings in which gabbro occurs:

- Mid-ocean ridges and oceanic crust: The lower portion of oceanic crust is commonly gabbroic. Seismic and drilling studies indicate a layered oceanic crust model where sheeted basaltic dikes and lava flows overlie gabbroic plutons.

- Ophiolite complexes: Fragments of oceanic crust uplifted onto continents (ophiolites) often expose gabbro directly. Classic ophiolites include the Semail Ophiolite (Oman), Troodos Ophiolite (Cyprus) and sections of the Mediterranean and California Coast Ranges.

- Large layered intrusions: On continents, enormous mafic intrusions such as the Bushveld Complex (South Africa), the Stillwater Complex (USA), the Skaergaard intrusion (Greenland) and the Rum intrusion (Scotland) contain extensive gabbroic sequences with striking layering and economic mineralization.

- Orogenic and rift settings: Gabbro may be emplaced in continental rifts and as part of intrusive suites associated with extensional tectonics.

Notable examples for field visits and study include the exposed gabbroic sequences in the Lofoten islands of Norway, the Isle of Rum in Scotland, and the gabbro of the Sierra de Guadarrama (Spain). Oceanographic expeditions have recovered gabbroic rocks from mid-ocean ridges and transform faults, providing direct evidence of deep crustal processes.

Gabbro in the Oceanic Crust

Geophysical studies of the oceanic crust show a characteristic layering: volcanic lavas at the top, sheeted dike complexes below, and gabbros at greater depth. Where tectonic uplift or obduction exposes oceanic lithosphere, geologists can examine the gabbros directly. Because gabbro crystallizes at depth, rocks recovered by drilling or uplift preserve records of slow cooling, cumulate processes and hydrothermal alteration that are not visible in surface basalts.

Physical Properties and Identification

Gabbro can be identified in hand specimen by its dark color, coarse-grained texture and a composition dominated by blocky white to gray plagioclase crystals surrounded by dark green to black pyroxene. When olivine is present, it appears as greenish grains, and significant olivine content may give the rock a darker green hue.

- Texture: phaneritic (coarse-grained), occasionally porphyritic if some crystals grew earlier than others.

- Color: dark gray to black, sometimes greenish when altered.

- Density: relatively high for igneous rocks due to Fe-Mg minerals—typical densities range from about 2.7 to 3.3 g/cm3 depending on mineral content.

- Hardness and durability: gabbro is hard and generally durable, making it useful as crushed stone and as dimension stone where aesthetic properties are acceptable.

Petrographic thin section analysis reveals clinopyroxene (augite) as a dominant mafic phase and plagioclase of labradorite to bytownite composition. Accessory minerals may include magnetite, ilmenite, apatite and sulfide minerals. Geochemical classification following IUGS principles distinguishes gabbro from related rocks by modal mineralogy and silica-alkali composition.

Practical Uses and Industrial Applications

Gabbro has found a variety of uses from bulk engineering applications to decorative stone. Its properties—hardness, availability and attractive polish in some varieties—contribute to its value.

Construction and Aggregate

Crushed gabbro serves as aggregate for road construction, railway ballast and concrete base. Its angular fragments interlock well, providing mechanical strength for pavements and foundations. Because it is durable and abrasion-resistant, gabbro is a preferred material in areas where long-term wear is a concern.

Dimension Stone and Ornamentation

Some gabbro varieties polish well and are marketed as ornamental stone under trade names such as “black granite” (a commercial, non-geological term for many dark igneous rocks used decoratively). Polished gabbro slabs are used for countertops, flooring, monuments and building facades. The dark, often speckled appearance makes it a visually pleasing choice for modern architecture and memorial stones.

Industrial Minerals and Mining

Large layered gabbroic intrusions can host concentrations of sulfide minerals enriched in nickel, copper and the PGE (platinum group elements). The economic significance of these intrusions is immense: the Bushveld Complex in South Africa remains the world’s largest source of platinum and related metals, and similar gabbroic bodies elsewhere are mined for base and precious metals.

Other Uses

- Dimension stone blocks for curbing, pavements and landscaping.

- Specialized crushed stone for heavy-duty surfaces and drainage.

- Geochemical exploration targets: gabbroic intrusions are primary targets when searching for magmatic sulfide deposits and associated mineralization.

Engineering Considerations and Weathering

When gabbro is used in construction, engineers evaluate its mechanical and petrophysical properties. It typically has high compressive strength, low porosity and good abrasion resistance, but local variations—due to fractures, alteration, or compositional heterogeneity—can affect performance. Serpentinization or hydrothermal alteration can reduce strength and increase susceptibility to weathering.

Freeze-thaw cycles and chemical weathering can lead to surface scaling on polished dimension stone if microfractures or alteration products are present. Proper selection, testing and installation mitigate these issues. In heavy civil works, geotechnical characterization (uniaxial compressive strength, point-load tests, and durability indices) is standard practice for determining suitability.

Scientific Importance and Research Topics

Gabbro plays a central role in several active research areas in Earth sciences. Because it records magmatic processes at depths not directly accessible at the surface, gabbro bodies are natural laboratories for studying magma chamber dynamics, crystal settling, and the development of layered intrusions.

Magma Chamber Dynamics and Layered Intrusions

Layered gabbroic intrusions display spectacular stratigraphy that documents the order of mineral crystallization and the movement of crystals and liquids within magma chambers. Researchers use field mapping, petrography, geochemistry and numerical modeling to reconstruct the history of these chambers—how they fill, differentiate and evolve over millions of years.

Oceanic Crust and Plate Tectonics

Understanding gabbro is essential to interpreting the structure and evolution of the oceanic crust. Drilling projects (such as those conducted by the International Ocean Discovery Program) and deep-sea dredging have recovered gabbros that constrain models of crustal accretion at spreading centers. Studies of ophiolites exposed on land provide complementary, easier-to-access records of oceanic crust formation and subsequent tectonic history.

Mineralization and Economic Geology

Research into sulfide segregation, metal partitioning and the physical processes that concentrate metals within gabbroic systems remains a high-priority economic geology topic. Understanding how and where metals accumulate informs mineral exploration and helps locate critical resources such as nickel and platinum-group metals.

Interesting and Lesser-known Facts

- The name gabbro comes from a small village in Tuscany, Italy, where early descriptions of dark coarse-grained rocks were made; the term was later adopted by geologists for this rock type.

- Commercially, many dark igneous rocks are sold as “black granite” even when they are true gabbros or diabases—this is a trade name rather than a geological classification.

- Gabbro and basalt are chemically very similar; their primary difference lies in texture caused by cooling rate. They are therefore petrologic equivalents—one form cooled slowly underground (intrusive), the other quickly at the surface.

- Large layered gabbroic intrusions can be hundreds of meters to many kilometers thick, preserving records of repeated magma injections and long-lived magmatic systems.

- When gabbroic rocks are uplifted and exposed at the surface, they can create rugged landscapes with resistant outcrops favored by climbers and outdoor enthusiasts.

Identification Tips for Students and Rock Collectors

For a quick field identification of gabbro:

- Look for a coarse-grained texture—individual mineral crystals should be visible to the naked eye.

- Identify the dominant minerals: blocky white-to-gray plagioclase crystals set in a darker matrix of pyroxene; olivine may be greenish.

- Compare density and hardness to nearby rocks—gabbro tends to be dense and hard.

- Use a hand lens and, where available, a thin section or X-ray diffraction to confirm mineralogy.

Collectors should be cautious: many similar-looking rocks (diorite, norite, diabase) require petrographic or geochemical analysis for precise classification. If a specimen contains abundant orthopyroxene rather than clinopyroxene, the correct name may be norite rather than gabbro.

Cultural and Architectural Uses

Beyond technical and geological significance, gabbro has cultural resonance in architecture and memorial art. Its durability and dark, dignified appearance make it suitable for monuments, gravestones and decorative interior surfaces. In some regions, local gabbro has been used historically in vernacular architecture, giving towns and monuments distinctive visual character.

Architects choosing gabbro as a finish should balance its visual appeal with considerations of polishing, sealing, and handling the material to prevent staining or weather-related deterioration. When used outdoors, knowledge of the rock’s alteration history and fracturing is essential to ensure long-lasting installations.

Concluding Remarks on Gabbro’s Role

Gabbro is both scientifically valuable and practically useful. Its role in the architecture of the oceanic crust, its presence in large layered intrusions that host critical mineral resources, and its physical characteristics that make it suitable for construction and ornamentation all underscore its importance. Whether encountered as a massive pluton exposed on a coastal cliff, as a polished slab in a building lobby, or as a target in mineral exploration, gabbro provides a direct link to the deep magmatic processes that shape our planet.