Fossil Coral occupies a unique place at the intersection of geology, paleontology, and the lapidary arts. Formed when ancient coral colonies are gradually replaced by minerals over millions of years, this material preserves intricate growth patterns and sometimes vivid coloration that make it prized both by scientists and artisans. In the following sections, we will explore what fossil coral is, where it is found, how it forms, and the many uses and cultural meanings it has acquired. The goal is to give a comprehensive picture of this remarkable natural substance, its scientific value, and its place in modern markets and traditions.

What Is Fossil Coral?

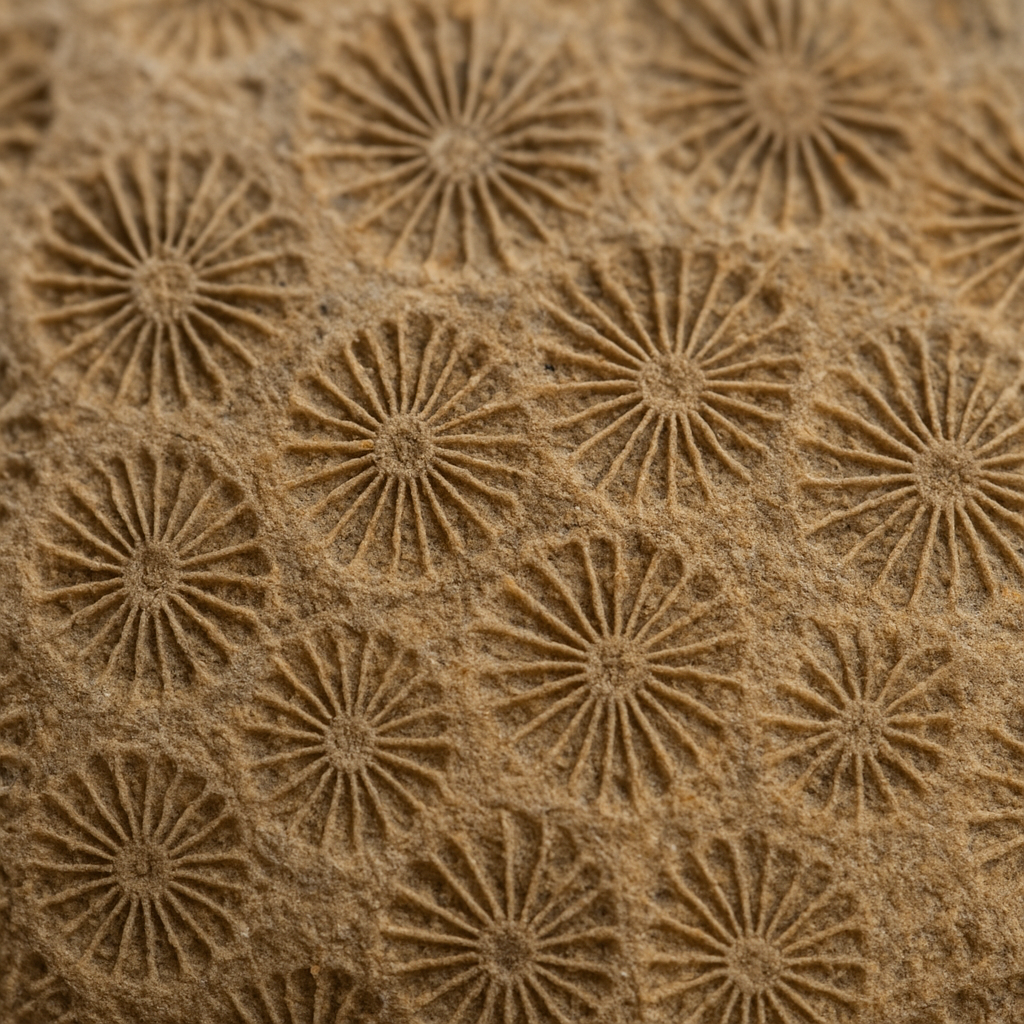

At the most basic level, fossil coral is the mineralized remains of coral colonies that grew in ancient seas. Coral, which today is most familiar as a living component of tropical reefs, is composed mainly of calcium carbonate in the form of aragonite when alive. Over geological time, the original aragonite skeletons can be dissolved and replaced by other minerals, commonly silica (quartz), calcite, or agate, in a process called petrifaction or fossilization. The result is a stone that retains the tiny corallite patterns—the radial symmetry and pore-like structures of individual coral polyps—even though the living tissue has long since vanished.

Two broad categories are often discussed in gemological and geological contexts:

- Coralloid fossils where the original carbonate material is largely preserved as calcite or aragonite and retains much of its original chemical composition.

- Silicified or agatized fossil coral, where silica replaces the original skeleton, producing a hard, durable material that can take a high polish and exhibit colorful banding.

Geological Formation and Age

The formation of fossil coral is a story of deep time and slow chemical change. Most coral fossils available today formed during the Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras, although younger fossil corals also exist from the Cenozoic. The transition from living reef to fossil involves several stages:

- Death of the coral colony and burial by sediment.

- Compaction and diagenesis, during which pore waters circulate and chemical reactions can dissolve original carbonate minerals.

- Replacement or infilling by silica, calcite, or other minerals transported by groundwater, preserving the structural details of the coral skeleton.

Silicification, the process that produces many of the attractive agate-like fossil corals used in jewelry, often happens when volcanic ash or silica-rich fluids percolate through sediments. The mineral replacement can occur over thousands to millions of years, depending on environmental conditions. Because fossil coral often preserves delicate structural details, it is an important window into ancient marine ecosystems and helps scientists reconstruct paleoenvironments.

Where Fossil Coral Occurs

Fossil coral deposits are distributed worldwide, but some localities are particularly famous for the quality, abundance, or unique appearance of their material. Notable occurrences include:

- Florida, USA — Extensive fossil coral beds, many from Pleistocene reef systems, occur along the peninsula and the Keys. These are often carbonate-rich and of interest to both geologists and collectors.

- Indonesia and the Philippines — Archipelagic regions with complex geological histories produce silicified fossil corals that are used in carved ornaments and jewelry.

- Madagascar — Known for a variety of fossil and agate materials, Madagascar can yield coral fossils with striking patterns and colors.

- Southeast Asia and parts of Australia — Ancient reef systems and associated sediments produce commercial material.

- Europe — Regions with Paleozoic reef complexes, such as parts of the United Kingdom and the Czech Republic, contain coralline fossils of scientific interest.

Different deposits yield different visual and physical characteristics. For example, silicified coral from Indonesia may be dense and take a high polish, making it ideal for cabochons and beads, whereas carbonate-based fossil coral from Florida may be softer and more porous, better suited for educational specimens and museum collections.

Uses and Applications

Fossil coral has found multiple applications across disciplines. Its combination of scientific significance and aesthetic appeal gives it a wide cultural and commercial footprint.

Scientific and Educational Uses

In paleontology and stratigraphy, fossil coral helps date rock sequences and reconstruct ancient marine habitats. Because coral growth is influenced by water temperature, depth, and chemistry, fossil coral can be used as a proxy for past ocean conditions. Thin sections of fossil coral examined under a microscope reveal growth bands and microstructures analogous to tree rings, allowing researchers to infer seasonal cycles and rates of growth. Fossil coral also helps in reef ecology studies and in understanding mass extinction events.

Lapidary and Jewelry

Many silicified fossil corals are used as a semi-precious gem material. When cut and polished, fossil coral cabochons exhibit radial patterns that are visually captivating. Common jewelry uses include:

- Cabochons for rings and pendants

- Beads and worry stones

- Carvings and inlays in decorative objects

Fossil coral is valued for its unique patterns and the sense of antiquity it carries. It often provides a more ethical alternative to harvesting living corals for jewelry, since many live coral species are protected.

Collecting and Display

Mineral collectors prize well-preserved fossil coral specimens for museum displays and private cabinets. Exceptional pieces that preserve the three-dimensional architecture of ancient reefs or show rare colors and silicification are especially sought after. Educational displays often pair fossil coral with modern coral samples to illustrate biological continuity and geological change.

Cultural, Historical, and Metaphysical Associations

Cultures around the world have long ascribed symbolic meanings to coral. While living red coral has been prominent in Mediterranean and Asian traditions, fossil coral has also accumulated meanings in modern metaphysical markets. Anecdotal and traditional claims include associations with healing, grounding, and strengthening emotional resilience. In contemporary crystal lore, fossil coral is sometimes recommended for people seeking connection to ancestral energies or for grounding in times of change.

From a historical perspective, fossil coral has occasionally been used in amulets and talismans. Empirical support for metaphysical claims is lacking, but the enduring human desire to connect objects to narrative and memory helps explain fossil coral’s continued popularity beyond purely scientific or aesthetic values.

Identification, Cutting, and Care

Identifying fossil coral reliably requires careful observation. Key diagnostic features include:

- Visible corallite patterns—small radial fans or star-like structures representing the individual polyps.

- Hardness and reaction to acids—calcareous corals will effervesce weakly in dilute hydrochloric acid, whereas silicified corals will not.

- Density and translucency—silicified coral tends to be harder and denser, often with lower porosity.

Lapidary work on fossil coral follows techniques similar to other semi-precious materials. Silicified pieces can be cut, shaped, and polished with standard diamond tools. Porous or calcitic specimens require more cautious handling and may be stabilized with resins. Care for fossil coral jewelry generally involves avoiding harsh chemicals and prolonged exposure to acids or strong heat; storing pieces separately prevents scratching.

Market, Ethics, and Conservation Concerns

The commercial market for fossil coral intersects with conservation because demand for coral-related products can encourage harvesting of live reefs when consumers do not differentiate between fossil and modern coral. Ethical sourcing is therefore important. Key considerations include:

- Verifying that material is genuinely fossilized and not treated or assembled from modern coral pieces.

- Preferring sources that are transparent about locality and extraction methods.

- Avoiding purchasing live coral or products derived from protected species.

Some fossil coral mines have environmental impacts, especially where bulk extraction disturbs sedimentary landscapes or coastal zones. Responsible collecting practices and regulation help mitigate these effects. In many cases, fossil coral is a more sustainable option for coral-like jewelry, provided that mining is carried out with environmental oversight.

Interesting Scientific Findings and Research Directions

Research on fossil coral continues to produce insights into ancient climates and reef resilience. Notable scientific directions include:

- Using isotope geochemistry—ratios of oxygen and carbon isotopes in coral skeletons—to reconstruct past sea surface temperatures and carbon cycles.

- Analyzing growth banding and microstructure to estimate rates of reef accretion and responses to environmental stressors.

- Comparative studies between fossil reefs and modern coral systems to inform conservation strategies for contemporary reefs threatened by climate change.

Because corals often form extensive reef frameworks, they provide a three-dimensional archive of environmental change over time. Interdisciplinary studies combining paleontology, geochemistry, and ecology aim to improve predictions about how current reefs might adapt or decline under rapidly changing conditions.

Practical Tips for Collectors and Buyers

If you are interested in acquiring fossil coral for science, collecting, or jewelry, consider the following practical tips:

- Ask for provenance: reputable dealers can usually provide locality information and geological context.

- Request or perform simple tests: a professional can help distinguish silicified coral from modern, dyed, or assembled materials.

- Consider the purpose: choose stabilized or silicified specimens for wearable jewelry; select well-preserved carbonate fossils for display and research.

- Respect local laws: collecting fossils is regulated in many regions, and permits may be required for significant finds.

Closing Thoughts

Fossil coral is more than just an attractive stone. It is a bridge between past and present, preserving the architectures of ancient life and serving modern needs—from scientific research to artistic expression. Whether appreciated in a museum case, worn as a polished cabochon, or studied for clues about Earth’s climatic history, fossil coral invites curiosity and respect. Its patterns are a reminder of deep time and of the complex processes that turn living ecosystems into the solid record of Earth’s history.