Mercury is one of those substances that fascinates and alarms in equal measure: a metal that flows like water, a historical symbol of transformation and mystery, and a modern environmental and public-health challenge. This article explores where mercury occurs in nature and industry, how it has been and is used, and several related topics that shed light on its chemistry, societal impact, and surprising connections to planetary science, technology, and culture.

Natural Occurrence and Chemical Properties

As an element, mercury occupies a unique place in the periodic table. It is the only metallic element that is a liquid at standard ambient temperature and pressure, a property that arises from relativistic effects on its electron structure. Its symbol Hg comes from the Latin hydrargyrum, meaning watery silver, a name that hints at both appearance and behaviour.

Where mercury is found in nature

- Mineral deposits: The principal natural ore of mercury is cinnabar (mercury sulfide, HgS), which occurs in hydrothermal veins associated with volcanic activity and hot springs. Historically, large cinnabar mines have supplied most of the world’s mercury.

- Atmosphere and geologic cycling: Mercury is emitted naturally from volcanic eruptions and the weathering of rocks. Atmospheric transport carries mercury globally before it deposits on land and water.

- Soils and sediments: Mercury binds strongly to organic matter and particulate matter, accumulating in soils and aquatic sediments where it can be transformed by microbes.

- Biological reservoirs: Small amounts of mercury are found within the tissues of living organisms; microbial activity can convert inorganic mercury into methylmercury, which is highly bioavailable and toxic.

Basic physical and chemical properties

Mercury is dense, silvery, and electrically conductive. It forms amalgams with many metals — alloys in which mercury dissolves other elements — a property exploited historically in gold and silver extraction. Key physical and chemical features include low vaporization point compared to many metals, significant vapor pressure at room temperature, and the ability to bond in multiple oxidation states (0, +1, +2), influencing its environmental chemistry and biological interactions.

Uses, Applications and Technological Roles

Historically ubiquitous, mercury has been used in a wide array of applications. Over the past decades many of these uses have declined or been banned due to concerns about toxicity and environmental persistence, but mercury still plays roles in several industrial and scientific contexts.

Traditional and historical uses

- Measuring devices: Mercury was widely used in thermometers, barometers, and manometers because of its uniform thermal expansion and visibility. Many jurisdictions now regulate or restrict such devices, replacing mercury with safer alternatives.

- Medicine and antiseptics: Mercury compounds were once common in topical antiseptics and preservatives. This has largely been abandoned because of health concerns.

- Gold and silver mining: Mercury amalgamation has been used for centuries to extract precious metals from ore and alluvial deposits; small-scale and artisanal mining remains one of the largest sources of mercury emissions worldwide.

- Industrial uses: Mercury was used in chlor-alkali plants (in older technologies) and in some electrical switches, relays, and fluorescent lamps.

Contemporary, regulated, or niche applications

- Scientific instruments: Certain laboratories still use mercury in specific reference standards and precision instruments where its unique properties are advantageous.

- Pharmaceutical syntheses and catalysts: In some specialized chemical syntheses mercury compounds appear as reagents, but safer alternatives are increasingly favored.

- High-tech and legacy devices: Some specialty electronics and lighting systems contain mercury; disposal and recycling programs aim to recover and eliminate mercury from waste streams.

- Amalgams in dentistry: Dental amalgams historically used mercury mixed with silver and other metals. Use has declined because of alternatives and regulations, although amalgams remain in place in many restorations worldwide.

Health, Environment and Regulation

Concerns about mercury focus on its neurotoxic effects, particularly in organic forms. The capacity of mercury to move through ecosystems and magnify in food webs makes it a global pollutant of special concern.

Pathways of exposure

- Inhalation of mercury vapor from spilled elemental mercury or industrial emissions.

- Consumption of fish and marine mammals contaminated with methylmercury, the toxic form that bioaccumulates in tissues.

- Occupational exposure in mining, processing, and some manufacturing settings.

- Historical exposures from medicinal and cosmetic products containing mercury compounds.

Toxicology and ecological impact

Methylmercury is particularly harmful to the developing brain. Prenatal and early-life exposures are associated with lasting cognitive and developmental deficits. Mercury also affects wildlife, impairing reproduction and behaviour in birds, fish, and mammals. The process of microbial methylation in sediments and wetlands converts inorganic mercury to methylmercury, which is readily taken up and concentrated in organisms through a process called bioaccumulation and further magnified up food chains (biomagnification).

Major historical incidents and policy responses

- Minamata disease: The industrial release of mercury into Minamata Bay in Japan during the mid-20th century caused severe poisoning in local communities, illustrating the catastrophic human health consequences of uncontrolled releases. The incident is commonly referred to by place name and has driven global awareness and policy.

- International agreements: The Minamata Convention on Mercury (adopted in 2013) is a global treaty to protect human health and the environment from anthropogenic mercury emissions and releases, regulating products, processes, and emissions.

- National regulations: Many countries have phased out mercury use in consumer products, restricted emissions from industry, and created programs for safe disposal and remediation.

Detection, Remediation and Safe Handling

Addressing mercury contamination requires reliable detection, effective remediation strategies, and strict handling protocols to prevent exposure and environmental release.

Analytical methods and monitoring

- Air monitoring: Specialized instruments detect elemental mercury vapor at low concentrations; continuous monitoring helps identify leaks and emissions.

- Water and sediment analysis: Laboratory techniques such as cold vapor atomic absorption spectroscopy (CVAAS) and mass spectrometry are used to quantify total and speciated mercury, including methylmercury.

- Biomonitoring: Measuring mercury levels in hair, blood, and tissues provides an indication of human or animal exposure and helps guide public health interventions.

Remediation approaches

- Containment and removal: Physical removal of contaminated soils and sediments is often necessary at heavily polluted sites, followed by secure disposal or stabilization.

- Capping and isolation: Sediment capping and engineered barriers can limit the release of mercury into the water column.

- Chemical treatments: Some remediation strategies involve converting mercury to less bioavailable forms or binding it to sorbents that reduce mobility.

- Bioremediation and phytoremediation: Research continues into microbial and plant-based methods to sequester or transform mercury, though these approaches pose challenges due to the persistence and mobility of the metal.

Safe handling and community practices

Minimizing risk requires strict industrial hygiene, careful storage and transport of mercury-containing devices, and emergency procedures for spills. Public education about limiting fish consumption (especially for vulnerable populations such as pregnant women and children) is a key preventive measure. Many communities now run mercury collection and recycling programs to remove mercury from consumer waste streams.

Planetary Mercury and Cultural Connections

Beyond the metallic element, the name Mercury evokes the innermost planet of our solar system and a long history of myth and science. The Roman god Mercury, messenger and trickster, lent his name to both the planet and the metal, fostering centuries of symbolic association.

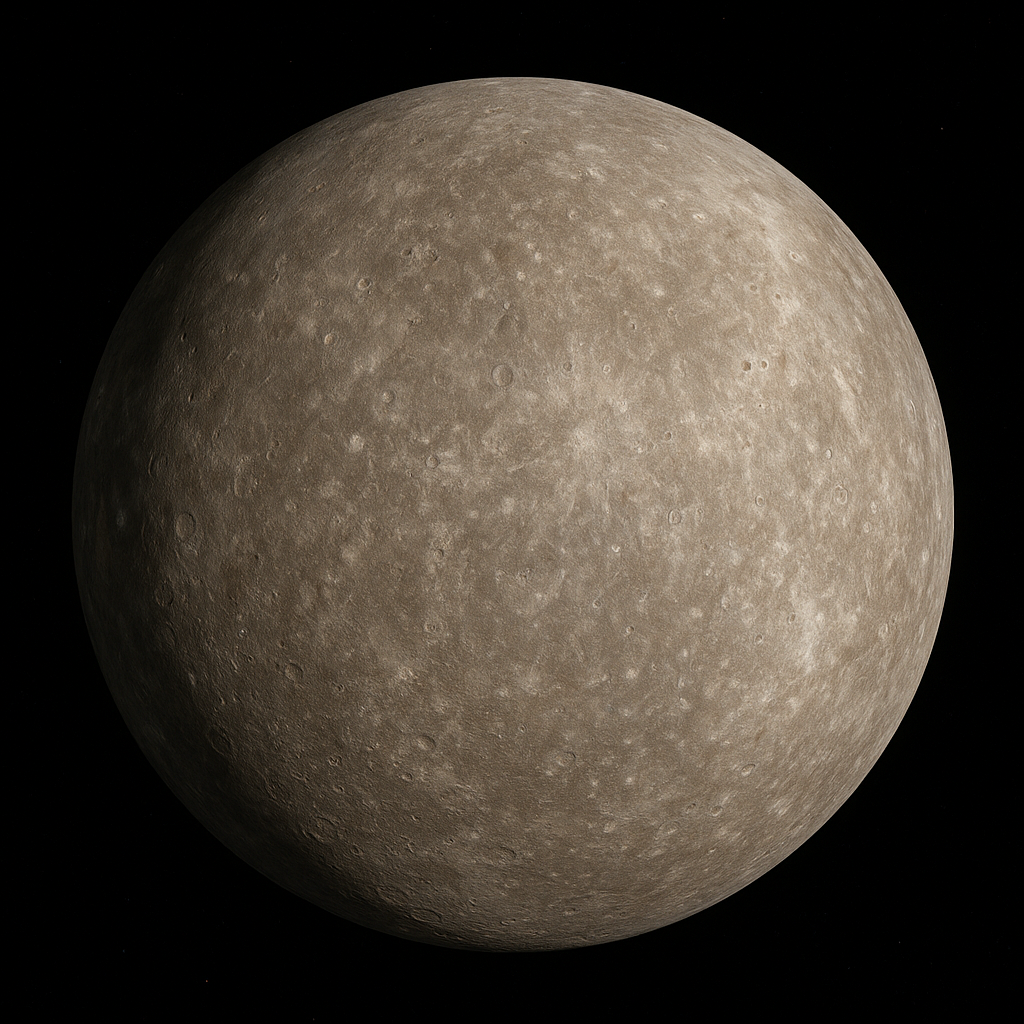

Mercury the planet

Planetary Mercury is a world of extremes: closest to the Sun, it experiences severe temperature swings and has a large iron core relative to its size. Modern missions have revealed a surface scarred by bombardment, ancient volcanic activity, and an unexpectedly complex geology. Though unrelated chemically to the metal, the planet’s name underscores humanity’s tendency to link natural phenomena symbolically and linguistically.

Cultural and historical anecdotes

- Alchemy and medicine: Mercury’s fluidity and reflective sheen made it an object of fascination for alchemists who associated it with transformation and transmutation.

- Mad hatter syndrome: The phrase originates from mercury poisoning among felt-hat makers exposed to mercury nitrate, which affected nervous systems and behaviour.

- Art and literature: Mercury has served as a metaphor and material in art, from early mirrors to contemporary installations that use its visual properties while navigating safety and environmental concerns.

Interesting Scientific and Practical Notes

Some facts about mercury are both scientifically intriguing and practically relevant:

- Unique metallic liquid: Mercury’s status as a dense metallic liquid at room temperature is uncommon among elements and central to many of its historical uses.

- Relativistic chemistry: The behaviour of mercury’s electrons is influenced by relativistic effects, which partly explain its low melting point compared with other heavy metals.

- Global pollutant: Because mercury cycles through air, water, and land and can travel long distances in the atmosphere, it is a transboundary environmental problem requiring international cooperation.

- Declining industrial use: Efforts to replace mercury in many technologies (thermometers, batteries, switches, lighting) have reduced use in many countries, though legacy uses and artisanal mining persist.

Research frontiers

Researchers continue to work on several fronts: developing better methods to detect and speciate mercury in environmental samples; finding effective and economically viable remediation techniques for contaminated sites; designing mercury-free alternatives for legacy technologies; and understanding the biogeochemical pathways that lead to methylmercury formation and accumulation in food webs. Public health research focuses on clarifying exposure risks, improving dietary guidance, and addressing the needs of communities affected by historical contamination.

Practical Advice and Final Remarks

When encountering mercury in daily life — older thermometers, antique barometers, some light bulbs, or dental fillings — the safest course is cautious handling and appropriate disposal through municipal hazardous-waste programs. Raising awareness about the environmental pathways and health risks associated with mercury helps communities reduce exposure and supports policies that limit future contamination. The story of mercury spans chemistry, industry, ecology, medicine, and culture, making it a powerful example of how a single substance can influence science and society on many levels.