Chalcopyrite is a mineral that has shaped human industry and scientific inquiry for centuries. As the most important ore of copper, it occurs in a wide variety of geological settings and plays a central role in modern metallurgy, mining economies, and materials research. This article explores the mineral’s physical and chemical characteristics, where it is found, how it is processed into metal, and several lesser-known but fascinating aspects of its role in technology and the environment.

Mineralogy and Physical Characteristics

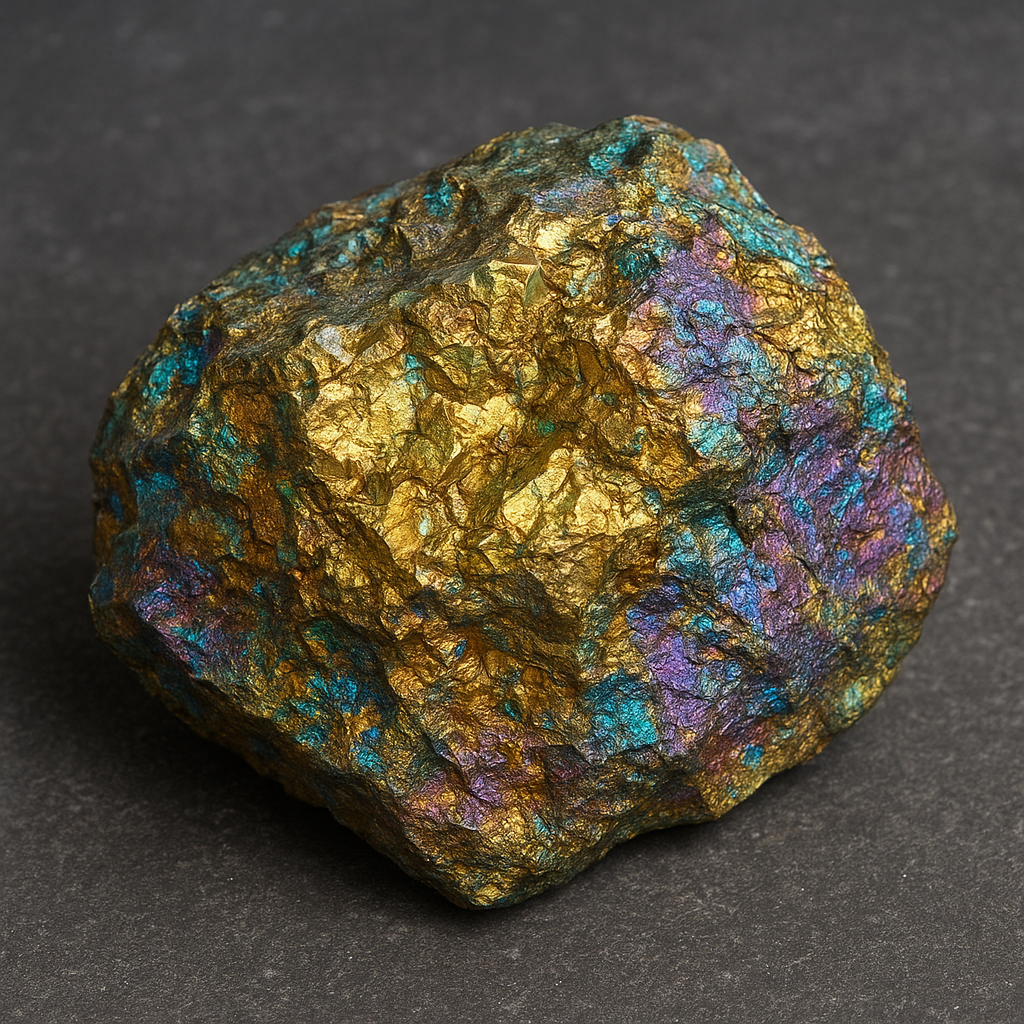

The mineral commonly known as chalcopyrite has the chemical formula CuFeS2. It belongs to the sulfide class of minerals and crystallizes in the tetragonal system, a fact that affects its habit and cleavage. Typical specimens exhibit a brassy to golden yellow color that often tarnishes to iridescent purples and greens, which can make high-quality samples visually striking for collectors. The luster is metallic, hardness ranges from about 3.5 to 4 on the Mohs scale, and specific gravity is roughly 4.1 to 4.3. Chalcopyrite’s streak is greenish black, distinguishing it from similar-looking minerals such as pyrite (which has a blackish-green streak) and bornite (which often shows a purplish tarnish but different composition).

At the atomic level, chalcopyrite’s crystal structure is important because it forms the prototype for a large family of compounds known as chalcopyrite-structure semiconductors. In natural chalcopyrite the arrangement of copper, iron and sulfur atoms gives it distinctive physical and electronic properties; these properties influence both how the mineral weathers in the environment and how it can be processed industrially.

Common associations and textural forms

- Massive and granular aggregates are frequent in ores.

- Well-formed tetragonal crystals are prized by collectors but less common in economic deposits.

- Chalcopyrite is typically intergrown with minerals such as pyrite, sphalerite, galena, and gangue silicates.

Where Chalcopyrite Occurs

Geologically, chalcopyrite is remarkably widespread. It forms in a variety of deposit types, and recognizing these settings helps explain where major copper resources are concentrated.

Major deposit types

- Porphyry copper deposits: These are among the world’s most important and largest sources of copper. Porphyry systems consist of large, low- to medium-grade ore bodies associated with intrusive igneous activity. Chalcopyrite is the dominant copper mineral in many porphyry deposits.

- Volcanogenic massive sulfide (VMS) deposits: These submarine hydrothermal systems often contain chalcopyrite together with zinc, lead, gold, and silver minerals.

- Skarns and hydrothermal veins: High-temperature fluids interacting with carbonate rocks can precipitate chalcopyrite in veins and replacement bodies.

- Sediment-hosted stratiform deposits and metamorphosed equivalents: Chalcopyrite may occur in these as part of complex sulfide mineralization.

Global distribution — notable regions

Large chalcopyrite-bearing copper deposits are found worldwide. Prominent examples include:

- Chile: The world’s leading copper producer, with giant porphyry deposits such as Chuquicamata and El Teniente.

- Peru: Home to several large porphyry and VMS mines.

- United States: Significant deposits in Arizona (e.g., Morenci), Utah, and other western states.

- Canada and Australia: Both countries host important porphyry and VMS-style chalcopyrite mineralization.

- Africa: The Copperbelt region (Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo) contains extensive copper–cobalt ores with chalcopyrite common locally.

- China and Russia: Substantial mining districts with chalcopyrite-dominated ores.

Chalcopyrite’s presence across diverse tectonic settings and ages is one reason copper has been extracted in many regions since antiquity.

Economic Importance and Industrial Processing

Chalcopyrite’s principal economic value stems from its copper content. The extraction and refinement chain from ore to finished copper is complex and has evolved significantly over time. Copper recovered from chalcopyrite becomes essential for electrical wiring, plumbing, electronics, motors, and countless manufacturing processes.

Mining and concentration

Because chalcopyrite often occurs in large, lower-grade bodies, large-scale open pit or underground mining is common. Ore processing usually starts with comminution (crushing and grinding) followed by beneficiation to concentrate the sulfide minerals. The most widely used concentration method is flotation, which separates hydrophobic sulfide particles from gangue using reagents and froth technology. Flotation produces a copper-rich concentrate typically containing anywhere from 20% to 40% copper depending on deposit and process.

Smelting and refining

Historically, chalcopyrite concentrates were smelted to produce metallic copper. Modern smelting involves roasting or matte smelting, converting to blister copper (~98–99% Cu), and subsequent fire refining or electrorefining to achieve high-purity cathodes. Smelting releases sulfur as sulfur dioxide, which can be captured and converted to sulfuric acid — a valuable byproduct used in hydrometallurgical processes and industry. Advances in furnace design and gas capture have reduced air emissions compared to older operations.

Hydrometallurgy and bio-processing

Chalcopyrite is relatively refractory to direct leaching under mild conditions because of its chemical stability. However, technological advances have introduced alternative extraction techniques:

- High-pressure acid leaching (HPAL) and oxidative pressure leaching in autoclaves can liberate copper from concentrates under extreme conditions.

- Bioleaching, using bacteria such as Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, accelerates oxidation of sulfide minerals and enables copper recovery at lower temperatures and potentially lower capital cost. Bioleaching is particularly attractive for low-grade ores and heap/stockpile processing.

- Solvent extraction and electrowinning (SX-EW) are used after leaching to separate copper and produce cathode copper without smelting in appropriate ore types.

The choice of process depends on ore mineralogy, environmental constraints, capital costs and the end-use requirements for the metal.

Applications Beyond Traditional Metallurgy

While most chalcopyrite is processed to produce copper metal, the mineral and its structural family have additional scientific and technological relevance.

Materials science and electronic properties

Chalcopyrite and its synthetic analogs are important in semiconductor research. Compounds with the chalcopyrite structure — such as CuInSe2 and other I–III–VI2 materials — are used in thin-film solar cells. The term photovoltaics is associated with these materials because they form the active absorber layers in some high-efficiency thin-film solar modules. Although natural chalcopyrite (CuFeS2) itself is not a mainstream photovoltaic absorber, its crystallographic archetype inspired a whole class of engineered semiconductors with tunable bandgaps and promising optoelectronic properties.

Researchers also study chalcopyrite for its electronic anisotropy, magnetic interactions (due to iron), and surface chemistry. Nanostructured sulfide materials related to chalcopyrite are being investigated for catalysis, electrocatalysis and as electrodes in energy storage devices.

Collecting, cultural, and historical uses

Chalcopyrite has a storied history in human metallurgy and culture. Its copper was exploited by pre-industrial societies — the Bronze Age’s supply of copper for tools and ornaments often derived from sulfide ores. Today, bright, iridescent chalcopyrite specimens are sought by mineral collectors and occasionally used in decorative pieces, though the mineral’s softness and tendency to tarnish limit jewelry applications.

Environmental Considerations and Social Impact

Mining and processing chalcopyrite-bearing ores pose environmental and social challenges that require careful management.

Acid mine drainage and tailings

Oxidation of sulfide minerals including chalcopyrite can generate acid mine drainage (AMD), which mobilizes heavy metals and sulfates and can contaminate waterways. Proper tailings management, water treatment, and progressive reclamation are essential to mitigate these impacts. Technologies such as constructed wetlands, lime neutralization, and biological treatment systems are used to remediate AMD.

Air emissions and sulfur handling

Traditional smelting releases sulfur dioxide, a pollutant that can contribute to acid rain and respiratory problems. Modern integrated smelters capture SO2 and convert it to sulfuric acid, reducing emissions while creating an industrial product. Regulatory regimes and new process technologies have driven substantial improvements in air quality near large smelting operations.

Social and economic dimensions

Large chalcopyrite deposits can be economic engines for regions, creating jobs and infrastructure. Conversely, mining can lead to displacement, changes in land use, and conflicts over water and environmental degradation. Transparent governance, benefit-sharing agreements, and community engagement are important for responsible development of chalcopyrite-hosting ore bodies.

Scientific Frontiers and Future Outlook

The future of chalcopyrite and related minerals is tied to global demand for copper, which is driven by electrification, renewable energy infrastructure, electric vehicles, and electronics. Meeting that demand will involve a mix of strategies: discovering new deposits, improving extraction efficiency, expanding recycling, and developing alternative materials where feasible.

Research trends

- Advanced mineral characterization: Electron microscopy, synchrotron studies and atom-probe tomography reveal chalcopyrite’s microstructures and alteration pathways, helping optimize processing strategies.

- Biohydrometallurgy: Improved microbial consortia and process controls aim to make bioleaching more predictable and widespread for chalcopyrite-bearing concentrates.

- Sustainable metallurgy: Cleaner smelting furnaces, emissions capture, and circular economy approaches are transforming the life cycle of copper derived from chalcopyrite.

- Materials innovation: Exploring chalcopyrite-type semiconductors and nanophases for energy conversion, catalysis and electronic applications.

As technologies evolve, the line between a simple mineral resource and a focus of advanced materials research becomes more blurred. The legacy of copper production derived from chalcopyrite continues to influence global industry, science, and geopolitics.

Why chalcopyrite still matters

Even with recycling and substitution efforts, primary copper production remains necessary. The scale and accessibility of chalcopyrite deposits make them crucial to securing future metal supplies. At the same time, ongoing improvements in extraction efficiency and environmental management are essential to ensure that chalcopyrite’s benefits are realized with reduced ecological footprint. Investigations of chalcopyrite’s surface chemistry, oxidation behavior and role as a structural prototype in semiconductor research keep it at the intersection of geology, metallurgy and materials science.