Chrysocolla is a vivid and variable mineral beloved by collectors, jewelers, and cultural historians alike. Its striking blue-green hues and intimate association with copper-rich environments give it a distinctive place among secondary copper minerals. This article explores where chrysocolla is found, how it forms, its practical and cultural uses, and several intriguing facts that connect geology, artistry, and history.

What Chrysocolla Is: Composition, Appearance, and Properties

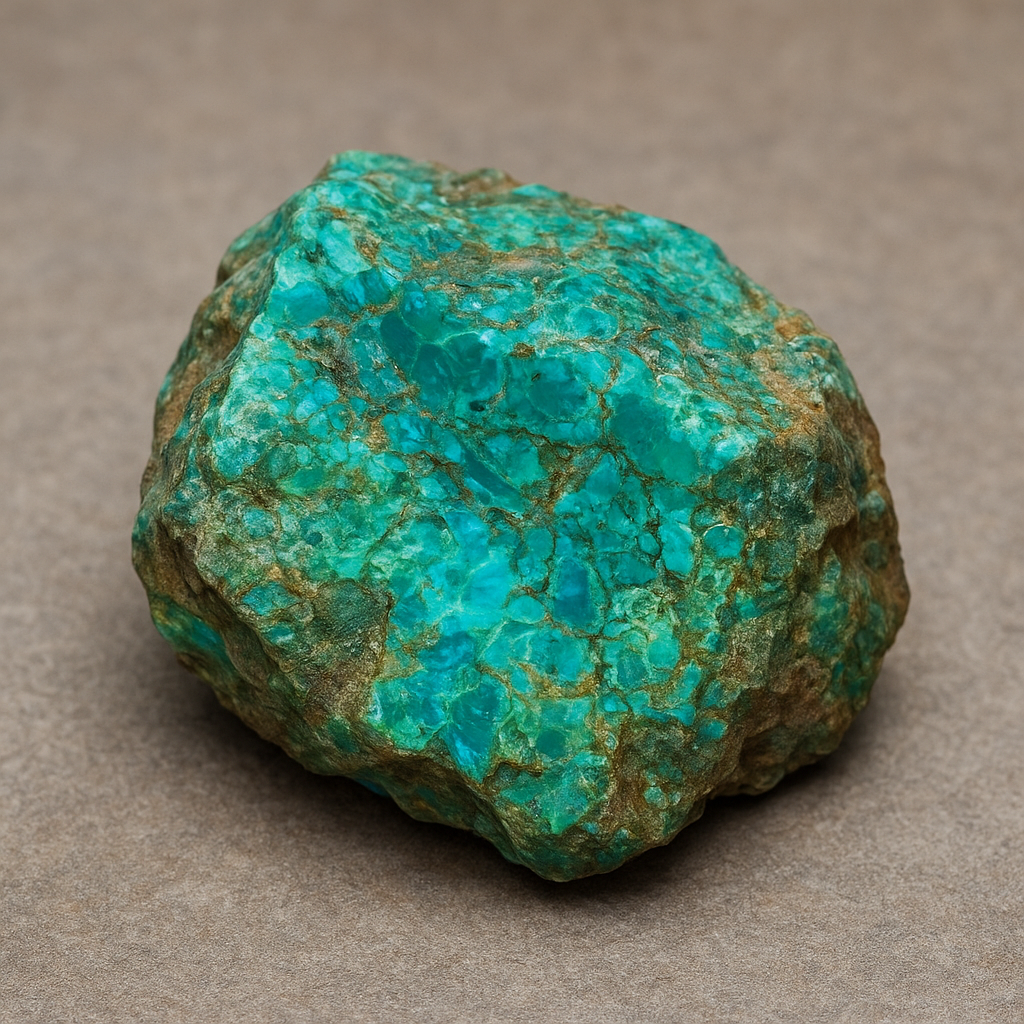

Chrysocolla is not a single, well-ordered crystalline mineral in the way quartz or calcite are. It is typically a hydrous copper silicate, often forming as a soft, massive, or botryoidal material with a glassy to dull luster. Chemically, chrysocolla is characterized by its content of copper combined with variable amounts of silica, water, and sometimes other metal ions. Because of this variability, specimens range from soft, earthy aggregates to denser, more durable masses where chrysocolla is intergrown with harder minerals.

Key physical properties

- Color: shades of blue, blue-green, and green depending on copper content and associated minerals.

- Hardness: variable, often between 2.5 and 7 on the Mohs scale when mixed with harder materials (pure chrysocolla is relatively soft).

- Luster: vitreous to dull, sometimes waxy or earthy in low-crystallinity specimens.

- Structure: commonly micro- to cryptocrystalline; rarely forms distinct crystals.

Because chrysocolla often occurs with other copper minerals, its exact appearance depends on the mineral matrix. Specimens with significant quartz or chalcedony content can be cut and polished into gems with greater toughness.

Where Chrysocolla Occurs: Global Localities and Geological Settings

Chrysocolla forms in the oxidized zones of copper deposits, typically near the earth’s surface where circulating groundwater and atmospheric oxygen alter primary copper sulfides. It is commonly associated with minerals such as malachite, azurite, and turquoise, and often occurs alongside secondary silica phases like chalcedony.

Major localities

- Peru — Known for attractive blue-green cabochon material and specimens from the copper belts in the Andes.

- Chile — Large copper porphyry deposits produce chrysocolla in oxidized zones; Chile is a major source of copper-associated minerals.

- United States — Arizona (notably Bisbee, Globe-Miami, and surrounding districts) and New Mexico yield classic chrysocolla specimens. Arizona is famous for colorful mixes of chrysocolla with malachite and azurite.

- Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia — Copperbelt regions produce interesting specimens and large masses associated with secondary copper minerals.

- Israel (Eilat) — The Eilat stone, a mixture often containing chrysocolla with azurite, turquoise, and malachite, has historical and cultural significance in the region.

- Mexico and Namibia — Notable for attractive lapidary material and collector specimens.

Geologically, chrysocolla appears in a range of settings: from the oxidized caps of sulfide deposits and fractures in basaltic rocks to weathered layers of porous host rocks where copper-bearing solutions precipitate secondary minerals.

Uses of Chrysocolla: Jewelry, Decoration, and Beyond

Traditionally valued for its color rather than hardness, chrysocolla has several practical and cultural uses. When mixed with harder materials or stabilized through lapidary techniques, it becomes suitable for ornamental and jewelry purposes. Many uses tie back to its striking hues and associations with copper-rich ore bodies.

Jewelry and lapidary work

- Cabochons and beads: When stabilized or backed by resin or a harder matrix (such as chalcedony or quartz), chrysocolla can be fashioned into gemstone cabochons and beads.

- Inlay and mosaics: The stone’s vibrant tones make it a popular inlay material for artistic objects and decorative boxes.

- Carvings and small sculptures: Softer varieties are carved into small forms but require care due to susceptibility to abrasion.

Lapidary artists often mix chrysocolla with harder minerals to create durable pieces. Common techniques include resin impregnation, backing thin slices with epoxy or jasper, and combining chrysocolla with other copper minerals in composite stones.

Industrial and historical uses

One of the most fascinating historical notes is the etymology of chrysocolla’s name: from the Greek chrysokolla, meaning “gold glue.” Ancient metalworkers reportedly used a copper-bearing substance resembling chrysocolla as a flux or soldering aid for joining metals. Whether the exact mineral used was classical chrysocolla or another copper compound, the association underscores early human interactions with copper minerals.

Beyond historical craft, chrysocolla has limited modern industrial use, since its softness and variability make it more valuable as an ornamental and collector mineral than as an ore source compared with primary copper minerals.

Care, Treatments, and Market Considerations

Buyers and collectors should be aware that chrysocolla’s variable hardness and porosity affect how it is handled and marketed. Proper care and knowledge help prevent disappointment.

Treatments and enhancements

- Stabilization: Many chrysocolla gems are stabilized with resin to reduce porosity and increase toughness for daily wear.

- Reconstitution: Powdered chrysocolla or small fragments may be mixed with binders to form composite stones; these are often labeled accordingly.

- Backing and boulder cutting: Thin slices are sometimes backed with epoxy or other material to add support for cabochons.

Because treatments influence value, reputable sellers disclose stabilization and composite status. Untreated, solid chrysocolla with attractive color and decent toughness is relatively rare and commands higher prices.

Care and maintenance

- Avoid harsh chemicals and prolonged exposure to acids or strong solvents, which can damage surface treatments or alter color.

- Clean gently with mild soap and lukewarm water; soft brushes can remove debris from crevices.

- Store separately from harder stones to prevent scratching; if the stone is stabilized, avoid ultrasonic cleaners and steam treatments.

Associated Minerals and the Eilat Stone Phenomenon

Because chrysocolla commonly forms in the oxidized zones of copper deposits, it is typically found alongside a palette of other secondary copper minerals. These associations create visually striking combinations sought by collectors and jewelers.

Common associates

- Malachite — green banding that contrasts with chrysocolla’s blues.

- Azurite — deep blue crystals that may occur as nodules or coatings.

- Turquoise — another copper-aluminum phosphate whose blue-green shades can blend with chrysocolla in decorative stones.

The famous Eilat stone (also called King Solomon stone) is a regional composite from the vicinity of Eilat in southern Israel, containing mixtures of chrysocolla, malachite, azurite, and sometimes turquoise. Its cultural resonance and historical associations make it a sought-after item in regional craft and jewelry.

Interesting Facts and Cultural Connections

Chrysocolla has intersected with human culture in surprising ways, from ancient metallurgy to modern metaphysical markets. Here are some noteworthy tidbits:

- Historical metallurgy: The name chrysocolla’s link to “gold glue” reflects ancient observations of copper minerals’ roles in metalworking; some sources suggest chrysocolla-like materials were used as fluxes in joining gold or as indicators of copper-bearing veins.

- Ancient artifacts: Blue-green pigments derived from copper minerals appear in artifacts and mural pigments across civilizations; while not always strictly chrysocolla, the family of copper minerals contributed to early color palettes.

- Modern metaphysical use: In crystal and healing communities, chrysocolla is often associated with communication, calm, and emotional balance. These uses are cultural and symbolic rather than scientific.

- Collector interest: Superb specimens showing dramatic color banding and interplay with other copper minerals fetch high collector prices; cut and polished doublets or stabilized pieces enable wearable art without sacrificing aesthetics.

Scientific and Environmental Notes

From a scientific standpoint, chrysocolla and its kin are useful indicators of near-surface geochemical conditions. The presence of chrysocolla signals oxidative weathering of primary copper sulfides and the mobilization and subsequent precipitation of copper in the presence of silica-rich solutions.

Exploration and environmental implications

- Explorers use secondary minerals like chrysocolla to trace underlying copper ore bodies; they can point to mineralized systems at depth.

- Mining and processing of copper-bearing ore can expose more rock to weathering, potentially forming additional secondary minerals in waste dumps and mine tailings; managing acid mine drainage and mobilized metals remains an environmental challenge in mining districts.

In some cases, chrysocolla and associated minerals form in the oxidized caps of old mine workings and natural outcrops, creating attractive displays but also serving as reminders of the geochemical cycles at play.

Imitations and How to Recognize Authentic Chrysocolla

The popularity of chrysocolla’s colors invites imitation and treatment. Common lookalikes include dyed howlite, stabilized turquoise, and glass. Recognizing genuine chrysocolla involves examining texture, hardness, and matrix relationships.

- Matrix and association: Authentic specimens often show natural intergrowths with malachite or azurite and have gradual color transitions; composites with backing or resin may reveal seams under magnification.

- Hardness testing: Pure chrysocolla is relatively soft compared to turquoise or glass; however, hardness alone is not definitive due to stabilization and composite materials.

- Professional testing: Infrared spectroscopy, electron microprobe, and careful visual inspection by experienced gemologists help confirm identity and detect treatments.

Collecting and Display: Tips for Enthusiasts

Collectors seeking chrysocolla should consider both aesthetics and authenticity. Provenance, condition, and treatment history all affect value.

- Provenance: Pieces from well-known localities (e.g., Bisbee, Eilat, or the Andes) often carry premium value and clearer histories; ask sellers about provenance and treatment.

- Specimen type: Choose between matrix specimens that showcase mineral associations and polished cabochons intended for jewelry. Each appeals to different collectors.

- Storage and care: Because of possible porosity and softness, store chrysocolla away from abrasive materials and avoid prolonged exposure to water or chemicals.

Final Thoughts on an Enchanting Copper Mineral

Chrysocolla occupies a special niche where geology meets art. Its vivid color palette, association with copper-rich environments, and long human history make it both scientifically interesting and aesthetically compelling. Whether admired as a raw specimen, set in jewelry, or studied for what it reveals about near-surface geochemistry, chrysocolla continues to fascinate collectors, jewelers, and geologists around the world. For anyone drawn to blue-green minerals, chrysocolla offers a rich story spanning formation, human use, and creative adaptation.