Azurite is a strikingly deep blue **mineral** admired by collectors, artists and geologists alike. Its intense color and historical presence in art make it more than a scientific curiosity: azurite has played roles in mining exploration, pigment technology and decorative stonework for centuries. This article explores azurite’s chemistry, physical characteristics, geological environments, notable occurrences, historical and modern uses, and a number of fascinating facts that connect mineralogy with culture and science.

Composition, Physical Properties and Crystal Structure

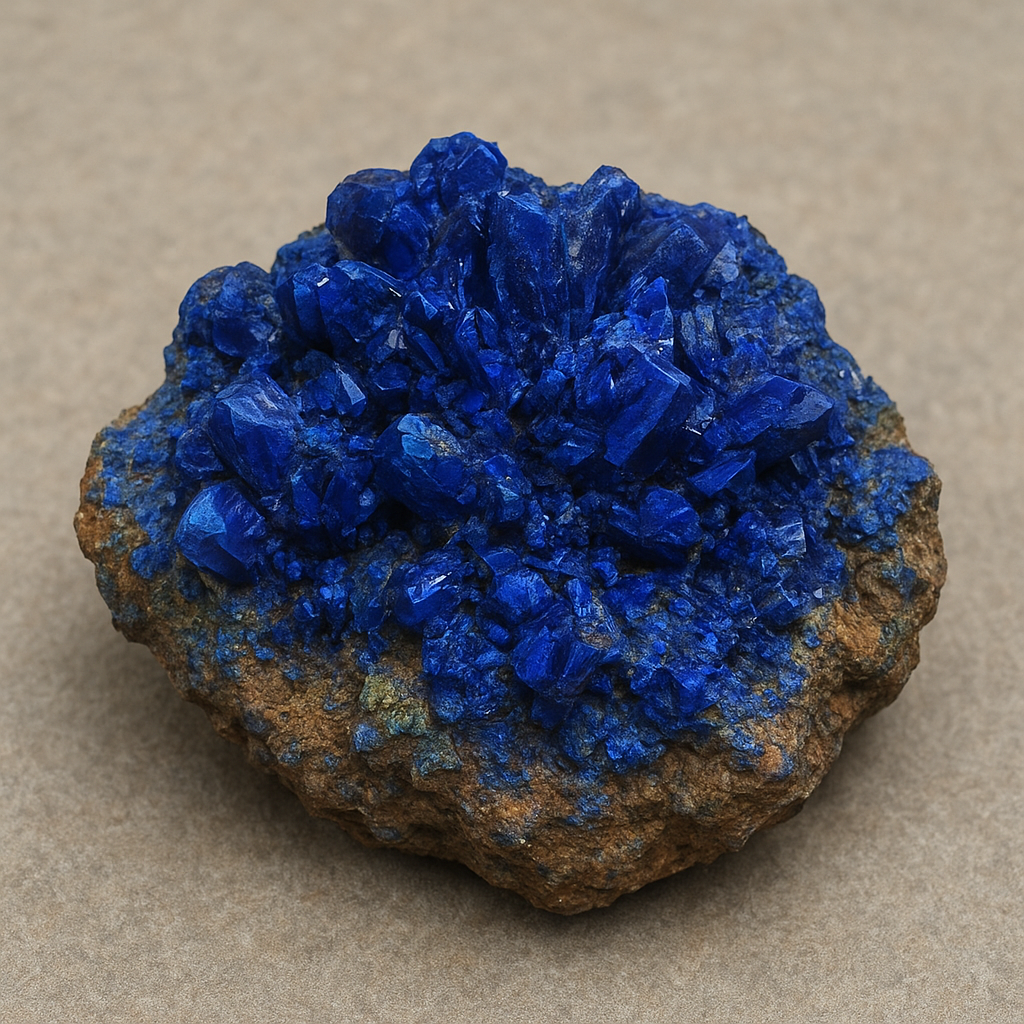

At its chemical core azurite is a basic copper carbonate, with the formula Cu3(CO3)2(OH)2. Copper is the defining metal in its structure and it is this element that gives azurite its deep blue hue. Azurite crystallizes in the monoclinic system, typically forming prismatic crystals, though it commonly appears as nodular, stalactitic or massive aggregates as well. When well-formed, crystals can show a vitreous to subadamantine lustre.

Key physical properties include:

- Color: vivid deep blue to azure blue

- Mohs hardness: about 3.5–4

- Specific gravity: typically 3.7–3.9

- Streak: light blue

- Reaction to acid: effervesces weakly with dilute hydrochloric acid because of its carbonate content

- Cleavage: distinct in one direction; brittle fracture

Because azurite is relatively soft and sensitive to environmental change, it is often found intergrown with and altered to the green copper carbonate malachite, which shares chemical kinship and frequently forms layered or mixed specimens with azurite.

How Azurite Forms: Geological Setting and Paragenesis

Azurite forms almost exclusively in the oxidation zones of copper ore deposits. When primary copper sulfides such as chalcopyrite, bornite or chalcocite are exposed to oxygenated groundwater and weathering processes, copper ions are mobilized. In the presence of carbonate-bearing solutions, copper precipitates as secondary carbonates, of which azurite and malachite are the most recognized.

Common paragenetic sequence

- Primary copper sulfides exposed by weathering

- Oxidation and mobilization of copper ions

- Precipitation of azurite where carbonate and slightly acidic conditions prevail

- Progressive alteration to malachite as conditions shift (pH, carbonate concentration, or continued exposure)

Azurite often occurs alongside other secondary copper minerals such as cuprite, chrysocolla, brochantite and native copper. It can form delicate crystal sprays, concretions, or botryoidal masses that are prized by collectors. The presence of azurite at the surface or in weathered rock is an important indicator for geologists searching for underlying copper mineralization.

Notable Localities and Global Distribution

Azurite is found on every continent where copper deposits have undergone oxidation. Some localities are famous for the quality, size or intensity of the blue color they produce. Classic localities serve as references for collectors and researchers.

- Chessy, France — The type locality near Lyon gave azurite one of its historic names (chessylite). Specimens from Chessy are historically important and were widely distributed through European collections in the 18th and 19th centuries.

- Tsumeb, Namibia — Legendary for exceptionally well-crystallized and colorful azurite associated with a remarkable variety of secondary minerals.

- Arizona, USA — Mines such as Bisbee, Morenci and the Copper Queen district have produced notable azurite specimens prized by collectors.

- Mexico — Regions around Zacatecas and other historic mining districts have yielded vivid azurite, often intergrown with malachite.

- Morocco — The Touissit and surrounding deposits in eastern Morocco are important sources of attractive, often botryoidal azurite.

- Australia, Chile, Democratic Republic of Congo, and various European historic mines — all have produced significant azurite specimens at different times.

Beyond these famous sites, smaller occurrences worldwide contribute to the mineral’s distribution and provide local mining communities with specimens for sale to collectors and lapidaries.

Uses and Applications

Azurite has had a variety of uses across history, many of them cultural or scientific rather than industrial. Its most prominent applications are:

Pigment and Art

Historically azurite was prized as a blue pigment in paintings and decorative arts. Ground into a powder and mixed with binders, it produced a rich blue used extensively in medieval and Renaissance painting. Over time, azurite may alter to malachite in paintings, causing blue areas to shift toward green and complicating conservation. By the 19th century azurite was largely superseded by synthetic pigments such as ultramarine and Prussian blue, which offered greater stability and consistency.

Lapidary and Decorative Uses

Because of its vivid color azurite is used in lapidary work for cabochons, beads and inlays. Due to its softness and potential for alteration, azurite is generally used for items that will not be exposed to rough wear or moisture. Often azurite-malachite combinations are used to create decorative tiles, sculptures and jewelry that display a dramatic blue-green contrast.

Indicator Mineral in Exploration

Geologists and exploration geochemists use azurite as a near-surface indicator of copper mineralization. Its presence can point to oxidized zones above richer sulfide deposits, guiding further exploration and drilling decisions.

Educational and Scientific Roles

Azurite is a common subject in mineralogy teaching — its vivid color, clear reaction with acids and association with malachite make it an excellent specimen for demonstrating weathering and secondary mineral formation. Analytical techniques like X-ray diffraction, Raman spectroscopy or XRF are used to study azurite in both geological and cultural (paint analysis) contexts.

Conservation, Care and Handling

Because azurite is relatively soft and chemically sensitive, proper care is essential for preserving specimens and objects that incorporate the mineral.

- Do not expose azurite to acids or strong alkaline cleaners; acid will attack the carbonate and cause damage.

- Avoid prolonged exposure to moisture and humid environments, which can promote alteration to malachite.

- Keep azurite away from heat and strong sunlight; thermal stress and photochemical changes can degrade color in some samples.

- For jewelry, protect azurite in settings that minimize abrasion and contact with water, perfumes or cosmetics.

- When cleaning specimens, use only gentle, dry brushing or very mild, controlled rinsing followed by immediate drying.

Associated Minerals and Alteration Processes

Azurite’s intimate relationship with malachite is one of the most visible examples of mineral alteration. Malachite, Cu2(CO3)(OH)2, is chemically related and often forms by the progressive replacement of azurite under changing environmental conditions. This can lead to interesting textures, such as banding or layered pseudomorphs where malachite preserves the original azurite crystal shapes.

Other common associates include:

- Cuprite (Cu2O)

- Chrysocolla (hydrated copper silicate)

- Brochantite and other sulfates

- Native copper and various iron oxides in the oxidized zone

These associations create complex and beautiful mineral assemblages that are studied for both their aesthetic and scientific value.

Cultural and Historical Notes

Azurite’s intense blue was historically coveted long before synthetic pigments existed. In European art, it is commonly found in panel paintings, frescoes and illuminated manuscripts. Conservators and art historians use chemical analysis to identify azurite and to understand how pigment choices affected the aging and appearance of artworks. In some regions, local peoples used azurite in ritual objects or as a means of producing blue dyes in antiquity.

The mineral’s name reflects its color: azurite derives from Persian and Arabic roots related to the word azure, meaning sky-blue. Alternative historical names such as chessylite evoke its classic French locality, while many languages incorporate the same blue-root in their common name for the mineral.

Collecting, Value and Ethics

Collecting azurite ranges from low-cost small samples to multi-thousand-dollar museum-quality specimens. Factors that influence value include:

- Color intensity and uniformity

- Crystal size and form

- Association with attractive matrix or contrasting minerals (malachite especially)

- Rarity of the locality or historical provenance

Ethical considerations matter: collectors should seek specimens with clear legal provenance and avoid material from conflict zones or illegally exported pieces. Many mining regions now have frameworks for responsible collecting; when buying specimens or artwork with azurite, choose reputable dealers who can document origin and extraction methods.

Interesting Scientific and Artistic Tidbits

– Azurite is often a subject in studies of pigment degradation because in paintings it can convert to malachite, influencing restoration strategies and our interpretation of original color schemes.

– Some of the most highly sought azurite specimens form velvety, botryoidal aggregates with a velvet-blue appearance; these specimens are visually distinctive and prized by collectors.

– On a microscopic level, azurite crystals can show complex twinning and zonation patterns that inform mineralogists about conditions of formation, such as changes in chemistry, temperature or fluid composition.

– Modern analytical methods such as Raman spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy and synchrotron X-ray techniques allow researchers to probe ancient azurite pigments non-destructively, revealing information about trade, technology and the sources of pigments used by artists across time.

Practical Tips for Enthusiasts

- If you plan to keep azurite specimens, store them in a low-humidity environment and avoid strong lighting to protect color integrity.

- When buying azurite jewelry, inspect the stone for stabilization treatments; some pieces are impregnated with resins to improve durability.

- Use non-invasive analytical services at museums or universities if you need to verify the composition of a historical pigment suspected to be azurite.

- Consider joining local mineral clubs or visiting museums with classic azurite displays to compare specimens and learn more about locality differences.

Azurite bridges the worlds of natural science, material culture and art history. Its stunning blue color made it historically desirable for pigments and ornamentation, and its geological role as an indicator of copper deposits has practical value for mineral exploration. Whether admired as a collector’s specimen, studied by scientists or observed as a trace left in an ancient fresco, azurite continues to captivate with its chemistry, color and story.