Pyrite is one of the most recognizable and widely distributed minerals on Earth. Its bright, metallic shine and brass-yellow color have fascinated miners, collectors, and scientists for centuries. Beyond its aesthetic appeal, pyrite plays important roles in geology, industry, environmental chemistry and even in the preservation of fossils. This article explores the mineral’s properties, global occurrence, practical uses and the scientific and cultural stories that make pyrite an intriguing subject.

Mineralogy and Physical Properties

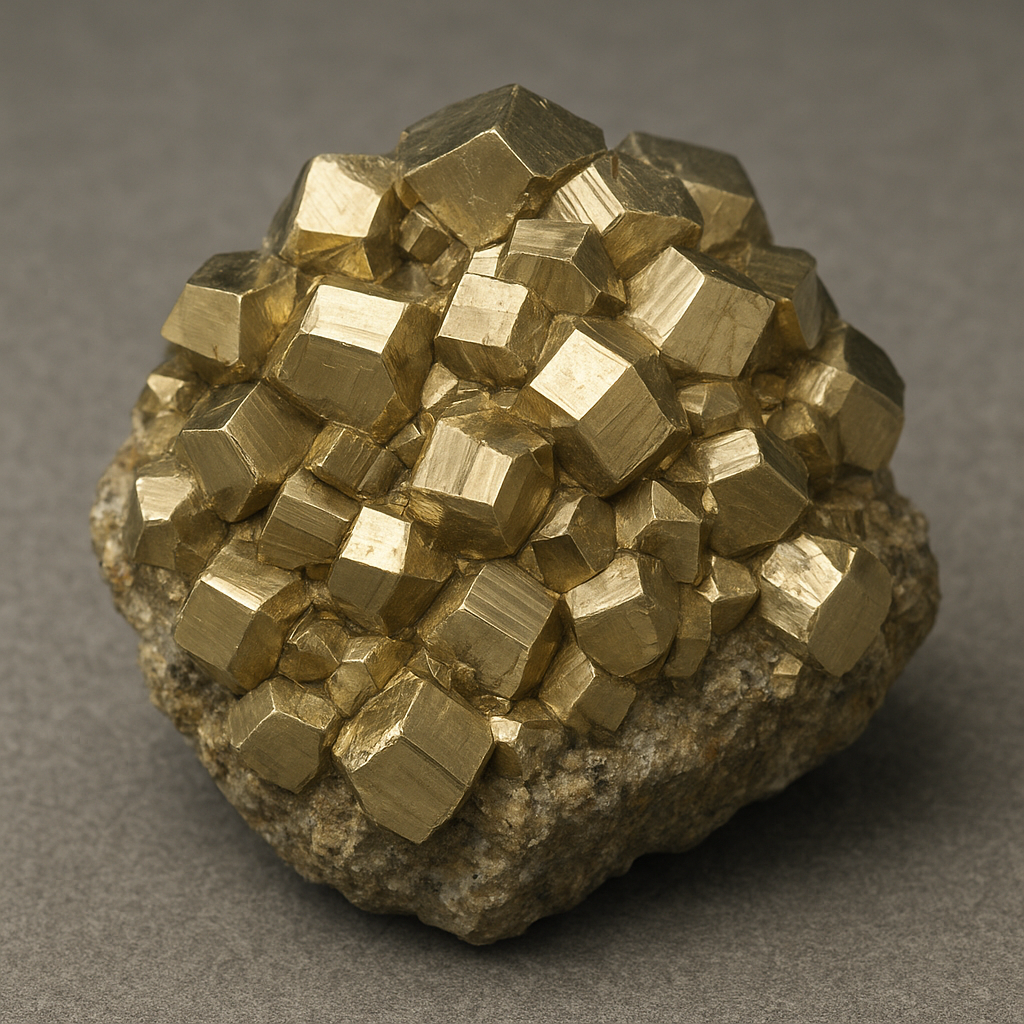

At its core pyrite is a crystalline sulfide of iron with the chemical formula FeS2. Chemically and structurally simple, it belongs to the isometric (cubic) crystal system and typically forms well-defined geometric shapes. The most familiar habit is the perfect cube, often with parallel striations on crystal faces, though pyrite also occurs as octahedra, pyritohedra and as massive granular aggregates.

Key physical characteristics help identify pyrite in the field and laboratory:

- Color: pale brass-yellow that may tarnish to darker brown or iridescent hues

- Luster: bright metallic and reflective

- Hardness: approximately 6–6.5 on the Mohs scale

- Streak: greenish-black to brownish-black

- Specific gravity: relatively high, around 4.9–5.2

- Brittleness: pyrite is brittle and fractures with a conchoidal to uneven surface

Pyrite should not be confused with its polymorph marcasite, an orthorhombic form of FeS2 that often forms tabular or spear-shaped crystals and is generally less stable. Another visually similar mineral is native gold, but gold is much softer, malleable and has a different streak and density.

Where Pyrite Occurs

Pyrite is cosmopolitan: it occurs in a vast range of geological settings and ages. It forms in igneous, metamorphic and sedimentary rocks and is particularly abundant in association with hydrothermal ores. Common occurrences include:

Hydrothermal Veins and Sulfide Deposits

Many sulfide ore bodies host abundant pyrite along with other sulfides such as chalcopyrite, sphalerite and galena. High-temperature hydrothermal systems precipitate pyrite from sulfur-rich fluids, commonly near vein margins and in massive sulfide deposits.

Sedimentary Rocks and Black Shales

In sedimentary environments, pyrite forms under reducing conditions where organic matter fosters sulfate-reducing bacteria. This microbial activity converts dissolved sulfate into sulfide, which then reacts with dissolved iron to precipitate pyrite. In such contexts pyrite frequently appears as fine-grained framboids—spherical aggregates of tiny crystals—or as nodules and coatings within mudstones and shales.

Coal Seams and Fossil Preservation

Pyrite commonly occurs in coal and along bedding planes where reducing conditions prevailed during burial. When organisms are rapidly buried in organic-rich sediments, they can be replaced or coated by pyrite, preserving delicate anatomical details—a process known as pyritization. Many exceptionally preserved fossil lagerstätten owe their preservation to pyrite replacement.

Notable Localities

- Navajún, La Rioja, Spain — world-famous for extraordinarily perfect cubic pyrite crystals with sharp edges and mirror-like faces

- Huanzala and other Peruvian mines — known for large and well-formed crystals often associated with other sulfides

- Rio Tinto district, Spain — historic mining district with vast pyrite-rich deposits

- Numerous hydrothermal districts worldwide, including parts of the United States, Canada, Australia and China

Uses, Economic Importance and Industrial Roles

Historically pyrite was mined as a principal source of sulfur and for sulfuric acid production. While modern industry obtains sulfur more efficiently from natural gas and petroleum refining, pyrite remains significant in several contexts.

Sulfur and Sulfuric Acid

In earlier centuries large pyrite deposits were roasted to generate sulfur dioxide, which was then converted to sulfuric acid—an industrial chemical central to many manufacturing processes. Today the direct use of pyrite for sulfur has declined, but it remains a potential local source where other sulfur resources are unavailable.

Gold and Base Metal Exploration

Pyrite is a common gangue mineral in many ore deposits. Importantly, pyrite can host microscopic inclusions of native gold or contain trace amounts of precious metals. Prospectors often analyze pyrite for gold or platinum-group elements as part of ore evaluation. In some gold deposits, the intimate association of gold with pyrite makes the latter a valuable indicator mineral.

Jewelry and Decorative Uses

Although brittle, pyrite has been used as an ornamental stone. Historically, jewelry labeled “marcasite” often actually contains polished pyrite set in silver. Care must be taken: pyrite can oxidize and stain settings or fabrics over time.

Emerging Technologies and Research

Pyrite’s mineralogical and electronic properties have attracted research interest for potential modern technologies:

- Photovoltaics: Because it is abundant, non-toxic and has a favorable absorption coefficient and bandgap (~0.9–1.0 eV), pyrite has been investigated as a low-cost solar absorber. Practical devices have been limited by surface recombination and charge-carrier problems, but research continues.

- Battery materials and catalysis: Pyrite and related iron sulfides are studied for roles in batteries, electrocatalysis and environmental remediation due to favorable redox chemistry.

Environmental and Health-Related Aspects

Pyrite’s reactivity with oxygen and water links it directly to several important environmental processes and concerns. The oxidation of pyrite liberates acidity and sulfate and can mobilize heavy metals:

Chemical reaction (simplified): 4FeS2 + 15O2 + 14H2O → 4Fe(OH)3 + 8H2SO4

This acid-generating reaction is the primary cause of acid mine drainage (acid mine drainage, AMD), a major environmental problem associated with mining of sulfide-bearing rocks. Low pH waters resulting from pyrite oxidation dissolve toxic metals (such as arsenic, lead, cadmium and copper), harming aquatic ecosystems and contaminating water supplies. Microbial communities, notably sulfur-oxidizing bacteria such as Acidithiobacillus species, catalyze and accelerate pyrite oxidation, exacerbating AMD.

Pyrite also poses issues for cultural heritage and construction materials. Pyrite-bearing aggregates or pyritic minerals in building stones can oxidize after construction, producing expansion, fracturing and staining known as “pyrite disease” in masonry and concrete. Collectors should store specimens in low-humidity conditions to minimize oxidative degradation and self-destruction of pyrite crystals.

From a human health perspective, pyrite itself is not highly toxic, but dust or weathering products associated with pyrite-bearing ores can contain hazardous elements. Proper industrial hygiene and environmental controls mitigate risk in mining and processing operations.

Identification, Analysis and Preservation

Identifying pyrite combines simple field tests with advanced analytical methods. Field identification rests on color, luster, hardness and streak. Laboratory and research tools include:

- X-ray diffraction (XRD) to determine crystal structure

- Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) for texture and elemental composition

- Electron microprobe and X-ray fluorescence (XRF) for quantitative chemistry, including trace element detection

- Raman spectroscopy and Mössbauer spectroscopy for electronic and bonding information

Collectors and museums must actively prevent pyrite decay. Preventative measures include controlling humidity (ideally below 40–50%), avoiding exposure to acidifying pollutants, using airtight display cases with desiccants, and isolating reactive specimens from sensitive materials. If pyrite has begun to oxidize and produce sulfate crusts, professional conservation may be necessary.

Cultural and Historical Notes

Pyrite has influenced human culture in many small but notable ways. Its bright shine and gold-like appearance led to the nickname fool’s gold among prospectors who mistook it for real gold. Historically, pyrite was used to generate sparks for fire-starting—when struck against steel or flint it can produce incandescent sparks, a property known and utilized before modern ignition methods.

In paleontology, the pyritization of fossils has yielded spectacularly preserved specimens, enabling detailed studies of ancient soft tissues and microstructures otherwise lost to decay. Such pyrite-replaced fossils occur in various lagerstätten around the world and have helped illuminate early animal evolution and taphonomic pathways.

Mineral collectors prize certain pyrite specimens both for form and rarity. The spectacular perfectly shaped cubes from Navajún, Spain are iconic, as are complex intergrown crystals and large drifted nodules. Collectible habits include “pyrite suns” (disk-like aggregates), pyrite roses and well-formed crystals displaying mirrored faces and striation patterns.

Interesting Scientific and Geological Aspects

Pyrite is a bellwether of past and present geochemical processes. Its presence in sedimentary rocks signals ancient reducing conditions and microbial sulfate reduction. In hydrothermal contexts it records temperature and fluid chemistry histories. Trace elements incorporated into pyrite—such as gold, arsenic, selenium and tellurium—serve as archives for ore-forming processes and are actively used in research to reconstruct ore genesis.

On a planetary scale, pyrite and other iron sulfides may play roles in astrobiology and the origin of life hypotheses. Iron–sulfur chemistry is fundamental to many biochemical pathways, and iron sulfide minerals are proposed as catalysts in early Earth scenarios that could have facilitated organic reactions in hydrothermal vent environments.

Conclusion

Pyrite is more than a pretty mineral: it is a key participant in geological cycles, an indicator for mineral exploration, a historical resource, a source of environmental challenges and a subject of active scientific research. From perfectly formed cubes prized by collectors to microscopic framboids preserving the remains of ancient organisms, pyrite reflects a wide range of processes at the interface of chemistry, biology and geology. Its ubiquity and diversity of forms ensure pyrite will remain a central topic in mineralogy and Earth sciences for years to come.